Slippery States

With artificial intelligence (AI) fully in use across businesses and an absence of any overarching federal rules, state legislators are forging their own paths in trying to regulate the technology due to the many risks it poses.

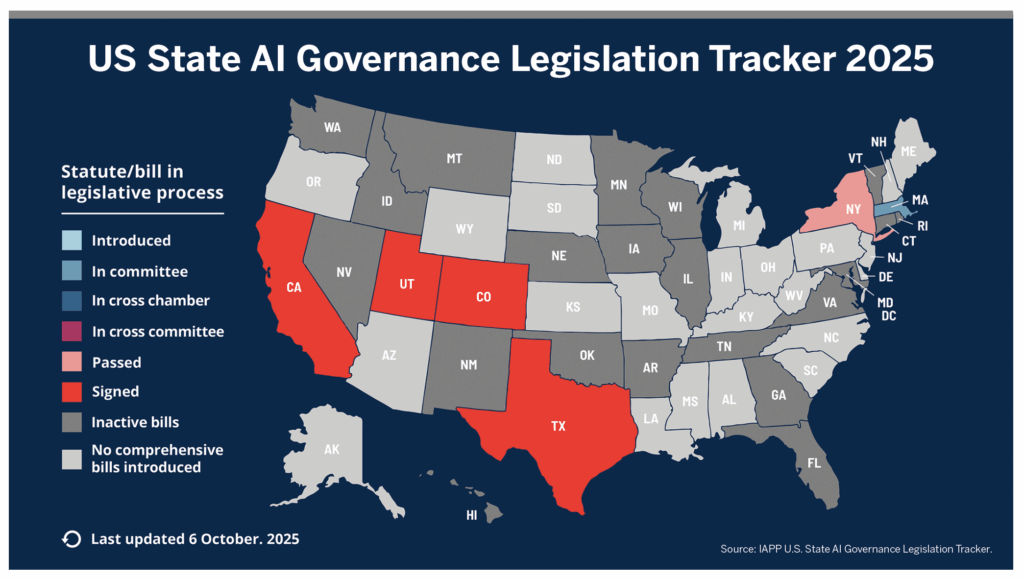

According to Stanford University’s 2025 AI Index Report, 78% of business organizations surveyed used AI in 2024, up from 55% the previous year. In 2024, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), lawmakers in 45 states introduced AI bills, with regulations adopted or enacted in 31 states. This year, NCSL reports at least 38 states have adopted or enacted around 100 measures. The collision between the rapid deployment of AI and inconsistent state regulations is reverberating across American businesses.

As more businesses use artificial intelligence, states are increasingly regulating those uses. In 2025 alone, no fewer than 38 states have adopted or enacted roughly 100 measures.

The jumble of state rules addresses matters encompassing the level of disclosure regarding a system’s purpose and operations, preventing discrimination in AI- based decisions, and opting out of AI processing of personal data. Lack of uniformity among the regulations means companies must comply on a state-by-state basis.

The federal government is unlikely during the Trump administration to pass legislation similar to the European Union’s AI Act in order to provide a superseding, consistent set of rules. The administration has preferred a lighter touch, even revoking an existing executive order laying out federal guardrails on AI development.

Managing so many diverse AI rules significantly increases the legal and administrative complexities and compliance costs for companies that operate nationally or in multiple states. State standards vary on matters including disclosure to users and the public about an AI system’s purpose and operations, whether systems should produce equitable and unbiased outcomes, discrimination, and people’s right to opt out of having an AI system process their data. These oblige companies to adapt their AI systems on a state-by-state basis.

State approaches to regulating AI range from comprehensive regulatory frameworks to issue-focused rules. Colorado, for example, in 2024 passed broad legislation that lays out obligations for AI developers and deployers, specifies consumer rights, and addresses other areas of concern. California, meanwhile, has adopted narrower bills addressing more singular worries: for instance, a set of bills last year to prevent use of deepfakes in election content.

New York and other states have focused regulations on frontier AI models, powerful systems that could cause high-severity events like mass casualties or economic damage in excess of $1 billion. Legislation passed this year by the New York state Assembly would require large AI developers to establish “appropriate safeguards” against critical harm and to report a safety event within 72 hours.

A company’s AI products or systems could be compliant in one state but violate rules in another state. Making compliance even more challenging, states like California, Colorado, Oregon, and New York frequently pass AI regulations and then amend or delay the rules in subsequent legislative sessions.

Maintaining compliance with the current patchwork of state AI regulations is “a nightmare for large businesses, shifting focus and resources from AI innovation to compliance,” says Timothy Shields, a partner at Kelley Kronenberg who leads the law firm’s data privacy and technology business unit. “Unlike the comprehensive regulations set forth in the European Union’s (EU’s) Artificial Intelligence Act, [compliance with] each state’s fragmented approach is a time-consuming and costly burden, compelling many companies to grudgingly accommodate the rules of the most restrictive state.”

The Range of Rules

Some of the most glaring inconsistencies in state rules involve lack of clear definitions about what constitutes “high-risk AI”—systems with the potential to drastically and negatively impact people. California’s definition, for instance, targets both specific high-stakes automated decisions and the possibility of catastrophic harm resulting from frontier AI models. By comparison, a new law in Utah cites “high-risk” AI interactions as involving the collection of sensitive personal data or the delivery of advice or services of a particularly personal nature (i.e., financial or medical).

States also have varying rules regarding when consumers and employees should be informed about AI use. Some laws require disclosure only under specific circumstances, while others set broader transparency requirements. For example, Colorado’s AI Act, which is scheduled to take effect Feb. 1, 2026, requires deployers to provide clear notice to consumers when a high-risk AI system is used to make a consequential decision about them. In Maine, businesses using AI chatbots for customer service or other consumer-facing roles must notify consumers that they are not engaging with a human.

Some states’ AI regulations focus on specific sectors or use cases. Illinois, for instance, is the leading state in regulating the AI analysis of biometric data like retina or iris scans, fingerprints, voiceprints, and hand or facial geometry scans. The state’s concerns involve the fact that biometric data, unlike passwords, cannot be changed if compromised, leading to a permanent risk of identity theft. The regulation requires companies to inform individuals in writing about the biometric data collection’s purpose and duration and to obtain a signed release.

Several states also are rushing to keep pace with the latest illicit uses of artificial intelligence. “Nowadays, AI frontier models can imitate anyone’s voice,” says Kevin Kalinich, who heads the global intangible assets team to identify and manage client AI and other emerging technology exposures at insurance broker Aon. “It’s so new and novel that Tennessee has passed a law prohibiting the use of AI to imitate the voice of Elvis Presley and other famous entertainers.”

The 2024 law, the Ensuring Likeness Voice and Image Security (ELVIS) Act, is considered a milestone in regulation of AI-generated content. While other states’ laws address the unauthorized use of a person’s face or voice for commercial purposes, Tennessee’s law was the first to specifically address AI-generated deepfakes. According to Ballotpedia’s Artificial Intelligence Deepfake Legislation Tracker, states have enacted 66 new laws related to deepfakes in 2025.

Shields cites specific examples of stressors placed on his clients by this mix of laws. They include a healthcare company whose AI-enabled recruiting system required state-specific programming and an insurance carrier whose AI underwriting tool adhered to federal fair lending laws but breached three distinct state AI regulations. “Rather than navigate the regulatory maze, the insurer abandoned the tool,” Shields says. For nondisclosure reasons, he could not discuss the cases in greater detail.

The varied AI regulations are also a major concern of risk management professionals, including corporate risk managers who buy insurance, making it difficult to assess liability, secure adequate coverage, and manage costs. “The regulatory patchwork for businesses operating across different jurisdictions makes compliance a complex and resource-intensive task to keep up with all the different rules,” says Lynn Haley Pilarski, chair of the Public Policy Committee at the Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS). “The inconsistent landscape creates confusion and lessens the efficiency of risk management professionals to efficiently do their jobs.”

The burden is particularly heavy on small businesses that have fewer resources to navigate regulatory demands that change at the state border, according to Sezaneh Seymour, head of regulatory risk and policy for cyber insurer Coalition.

“While large corporations can hire teams dedicated to legal and compliance work, smaller firms often lack the resources to navigate conflicting rules, putting them at greater risk. Regulatory balkanization not only disadvantages small businesses, but also creates confusion that can undermine the goals of regulators and the safe adoption of AI across sectors,” she said in a statement to Leader’s Edge. “The experience with data privacy laws demonstrates that layering different state requirements leads to inefficiency, legal risk, and, especially in the context of wrongful data collection, serious economic consequences.”

Depending on the industry sector, AI systems expose organizations to a range of liabilities, including algorithmic bias and discrimination, intellectual property infringement, operational errors, and privacy violations. The fragmented laws further expand the perilous legal minefield, crippling the fundamental insurance practices of risk assessment and underwriting, leaving businesses exposed to significant and unpredictable liabilities that change by jurisdiction.

Sources discussed the challenges in the context of insuring agentic AI systems that gather and interpret data to make autonomous decisions.

Under the Colorado AI law, a high-risk consequential action could be a bank using agentic AI to determine if a client meets the criteria for a loan, a university applying the technology for financial aid decisions, or an insurer using it to decide whether to pay out a claim, says John Romano, a principal at Baker Tilly and leader of the advisory, tax, and assurance firm’s internal audit and enterprise risk management service line.

“The question is whether a failure to disclose such actions is covered under a traditional E&O policy or other policies like cyber, crime, and fidelity,” he adds. “That’s why insurance brokers are so important.”

The solution to this regulatory maze would seem to be a single, comprehensive AI law like the EU’s AI Act. Uniform federal regulations would supersede the confusing hodgepodge of state laws, presenting consistent rules for AI system transparency, security, risk assessment, and disclosure. The level of consistency and specific obligations depends on the risk category an AI system falls into—unacceptable, high, limited, or minimal. The approach ensures that regulations are fair and appropriate, lowering the cost of following the rules and helping to generate the public’s trust.

“A targeted federal approach can establish clear and consistent expectations for how to use and secure AI, allowing smaller businesses to comply more easily. Importantly, policymakers can look beyond imposing new laws or regulations, which can often be rigid and lack the dynamism needed for emerging technology,” Seymour noted. “They can instead issue policy statements to clarify their expectations for how AI will be developed and used in a manner that protects individuals’ rights and safety, maintains security and trust, and safeguards against harm or bias.”

Federal Regulation Unlikely

A federal law governing the risks caused by the rapid deployment of AI across businesses is doubtful during the Trump administration, however. In the first days of his second term, President Donald Trump revoked the Biden administration’s executive order establishing federal guardrails for development of AI. The order included developing standards for detecting AI-generated content, such as watermarking, directed the development of AI tools to find and fix software vulnerabilities, and called for addressing the use of AI by adversaries, among other measures.

Although the president’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” originally contained a 10-year moratorium on enforcement of all state AI regulations, the provision faced bipartisan opposition and was stripped from the legislation in July 2025. The same month, Trump released “America’s AI Action Plan,” proposing to limit federal funding to states that pass burdensome regulations suppressing AI innovation. However, the executive branch’s power to preempt state law is legally questionable, as is the concept of federal funding hinged to a state’s AI regulations.

“The administration’s stance,” says Shields, “is that AI regulations will stifle innovation at a time when there is an arms race of sorts over AI development. The risk is it will move [outside the United States] to a more favorable jurisdiction.”

Trump’s tough position on state funding does appears to be having an impact. Due to the AI Action Plan, Colorado in August 2025 delayed enforcement of the state AI Act, considered the most comprehensive and sweeping such regulation in the United States, by six months to June 2026. Other factors in the delay included concerns voiced by technology companies and business groups over the stringent requirements. The regulation would require AI developers and deployers to provide consumers with disclosures on how their systems work, a level of transparency not found in other state regulations.

Minus a comprehensive federal law, states are likely to pass their own AI-related rules.

“In the absence of a unified federal approach, state lawmakers have a greater impetus to pass their own AI laws to protect their citizens,” says John Farley, managing director of the cyber liability practice at insurance broker Gallagher. “That’s resulting in…a fragmented state regulatory environment mirroring the longstanding difficulties companies have faced complying with state-regulated data privacy and breach notification requirements. Since no broad federal law existed, every state enacted its own regulations, each state attorney general looking to make their law tougher than the next state.”

Shields says he believes the fragmented regulatory environment is likely to remain the status quo for some time. Businesses must be proactive, getting in front of brewing regulations: “Actively track and closely monitor state AI regulations and any shifts in federal policy.”