Into the Metaverse

The metaverse can be many things to many people.

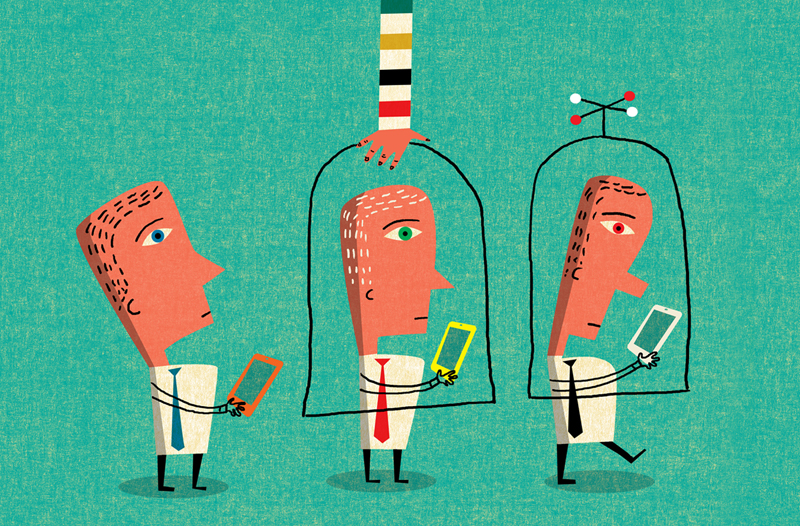

In fact, the term has been used for a variety of applications and technologies. At its core, the metaverse is a virtual platform that can be accessed through different devices, where avatars (virtual people/computerized characters) move through different digital environments. But for some, it is more than just a new technology. “I see the metaverse as a cultural inflection point for our society,” says Justin Jacobs, senior vice president of marketing at IMA Financial Group. “The metaverse is a transition period in which we as a society will put serious value on the digital representation of ourselves, our businesses and of the world at large.”

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently rebranded Facebook to cater its business toward the metaverse.

Metaverse platforms such as Decentraland and The Sandbox are selling virtual real estate for millions of dollars to organizations

and investors.

More than a thousand tech firms have partnered to create the Metaverse Standards Forum.

Buying Frenzy

The metaverse has big champions, so competition is fierce. During a recent earnings call, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who recently rebranded Facebook to cater its business toward the metaverse, mentioned an increase in competition with large tech firms—such as Apple—to build the metaverse. Similarly, Microsoft recently acquired Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion, the largest deal for any video game company to date, citing a direct investment in the metaverse. More specifically, the deal allows Microsoft to pick from a broad variety of game developers that have large player bases and strong capabilities at building virtual worlds to develop Microsoft’s presence in the metaverse.

Fascination with the sector has also sparked opportunities for smaller players to develop new digital assets within the metaverse. Racing to build their own digital worlds, metaverse platforms such as Decentraland and The Sandbox are selling virtual real estate for millions of dollars to organizations and investors. By further developing their virtual real estate, such as building virtual stores and shops, companies add additional value to the digital world by attracting a larger audience. Companies such as Atari, Samsung and Adidas have each bought virtual real estate. The hope for these companies is that, as more investors and users join these metaverse platforms and increase website traffic, the more valuable their virtual land will be. Similar to physical real estate, companies set up shop in virtual towns and cities where there is high foot traffic in the hopes users will purchase goods for their avatars.

In order for the metaverse to realize its full potential, many say, a foundation of open standards and interoperability is key. For this purpose, more than a thousand tech firms partnered to create the Metaverse Standards Forum. “The Metaverse Standards Forum is a unique venue for coordination between standards organizations and industry,” says Neil Trevett, president at Khronos Group, which maintains royalty-free interoperability standards for 3D graphics, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and machine learning. “Its mission is to foster the pragmatic and timely standardization that will be essential to an open and inclusive metaverse.”

Following all this activity, Citigroup speculates, the market for metaverse platforms and applications could grow up to $13 trillion by 2030 and see around five billion users. With so much attention pouring into the metaverse, brokers and insurers are taking notice and investing their resources to innovate and underwrite this new digital frontier.

One of the largest concepts the metaverse is pushing is the implementation of Web 3.0. Similar to how blockchain technology gave rise to decentralized finance, Web 3.0 promises to decentralize the internet.

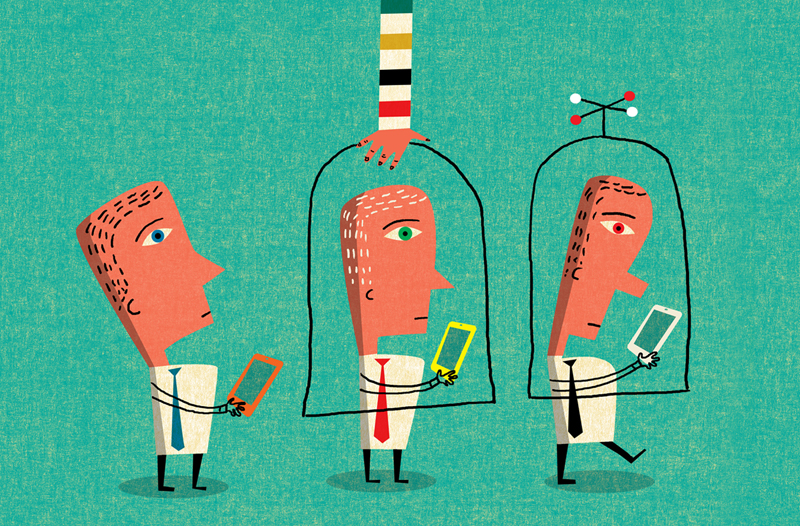

Web 3.0 would allow users in the metaverse to maintain their data security and online privacy through tokenization and smart contracts. Similar to investors housing their cryptocurrencies on non-custodial wallets, Web 3.0 would allow users to house more than just digital money. With Web 3.0, participants of the metaverse would be taking more control of the data collection one expects when visiting a website. Similar to the risks regarding decentralized finance, users who participate in Web 3.0 will be solely responsible for maintaining their own data and digital assets.

Insurers Enter the Metaverse

While the metaverse is still in its early development, some in the insurance industry have begun investing in it. For example, IMA announced earlier this year the formation of Web3Labs, a metaverse incubator where the company can test and bring to market risk and insurance strategies specific to the metaverse and Web 3.0.

“Web3Labs is our research and development facility for any insurance investment into Web 3.0,” Jacobs says. “It’s primarily designed to understand metaverse platforms and metaverse-based risks. This will allow us to develop risk mitigation solutions and then, putting in the first real groundwork, to build risk-transfer options for metaverse risks.”

Following up on the trend set by JPMorgan, the first bank to open a virtual physical office in Decentraland, IMA’s Web3Labs has announced the opening of a new virtual office within the same prominent metaverse platform. “We believe that metaverse-related risks can only be learned with firsthand experience,” Jacobs says. “So having a virtual office in Decentraland allows our team and risk advisors to understand what this new environment is like and to really get comfortable with it.”

By building a virtual office in Decentraland, IMA might also look into utilizing other forms of metaverse and blockchain-based technologies. These additional investments could lead to the integration of many new features, such as the use and development of cryptocurrencies, into the firm’s existing business models. “At some point in the future, we’d like to process metaverse risk transactions solely from inside a metaverse platform,” Jacobs says. “Now, whether that means we will accept cryptocurrency or develop our own IMA crypto hasn’t been decided yet. But we want to fully grasp the opportunities these platforms can offer so we can make insurance information more accessible to the right people.”

Similarly, other insurance brokerages are investing in physical infrastructures to prepare for a metaverse future. For example, hubb—a U.K.-based commercial insurance brokerage that uses its proprietary AI, automation and data-science platforms to offer insurance products—recently shifted its hybrid work strategy to the metaverse, utilizing virtual-reality devices.

“The practical aspects of transitioning from a hybrid to a VR work strategy haven’t been particularly complicated,” says Ed Halsey, co-founder and COO at hubb. “However, the cultural implementation aspect, like convincing team members that VR isn’t just a toy for gamers but a business tool that enables greater levels of connection and collaboration between workers and clients, takes time.”

Regardless of whether the investments are made in physical or virtual technologies, the goal seems to remain the same. “The real benefit of implementing metaverse applications is to make sure we’re comfortable with the technology before it becomes widespread, rather than playing catch-up during mainstream adoption,” Halsey says.

Are Metaverse Risks Insurable?

“The short answer is there’s a lot of unknowns right now,” says Jonathan Mitchell, director of customer success at insurance brokerage Founder Shield. “It’s difficult for our industry to build insurance products based on something so new. There’s a desire to bring valuable insurance products to metaverse consumers, but how can insurers account for losses that have never occurred before?”

Lack of historical data is a problem in the insurance industry for many emerging topics, among them cyber risk and decentralized finance applications. In the case of the metaverse, however, insurers can begin to use data from existing insurance products that may resemble some of the metaverse risks—trademark-related claims in social media, for example, says Rachel Jenkins, managing director of customer success at Founder Shield. “This sort of insurance product, which didn’t exist until three years ago, is in high demand from companies that partner with influencers on social media to promote their brands and products,” Jenkins says.

As people become more immersed in the metaverse, using physical VR and AR devices, the risk exposure resembles that of existing liability that can be found in esports (professional videogaming). Injuries such as collapsed lung from poor breathing and posture, carpal tunnel syndrome and back pain are common for professional esport players. “I think esports are, without a doubt, the closest proxy we have for how the insurance marketplace around the metaverse is going to evolve,” Jacobs says. “These markets are very similar both from a platform development perspective and a risk transfer perspective.”

In a similar fashion, existing coverage on the use of VR headsets in the workplace can be extremely helpful in analyzing the potential physical harm employees can cause—to themselves and one another—while being immersed in the metaverse. “The closest example of coverage from using VR headsets in the workplace is a combination of VR and drone coverage, which is becoming more prevalent in industries—like construction or oil and gas—that require faster and safer inspection processes for their facilities,” Jacobs says. “In some cases, the employees controlling the drones use VR headsets for more precise maneuvering. So, if they were to get injured while wearing VR headsets, then they’d be covered via workers compensation.”

Transferring Virtual Risks

With yet another technological innovation set to disrupt the industry, insurance brokers find themselves with more work to do when it comes to being ready for the metaverse. “As the popularity of metaverse platforms increases, the insurance industry will need to find a cost-effective way to transfer metaverse-based risks,” says Joseph Annarumma, an underwriter at Scale Underwriting, part of the Founder Shield family. “While that is mostly done by carriers, brokers will need to work closely with them to develop a way forward together.”

To do so, however, brokers will need to develop a detailed knowledge of the metaverse and to fully understand its risks and, more importantly, the behavior of its users. In some circumstances, that might also mean brokers will need to interact with clients where they are most comfortable, even in the metaverse itself. “The role of brokers can easily change based on the success of the metaverse and its applications in the future,” Annarumma says. “With new forms of risk transfer via digital platforms, the role of brokers can evolve to include administration and development of coverages for those types of virtual programs.”

In addition to evolving the way they do business and interact with clients, brokers might also be required to make additional investments in their workforce to develop new skills. “In such a scenario,” Annarumma says, “brokers may need to be as proficient in coding as they are in policy language, so they would require a brand-new set of skills.”

The digitization of actions in everyday life has evolved at a rate only few had predicted. As a result, the insurance industry is beginning to consider the importance of metaverse platforms and is bracing for any cultural changes that may come with this new technology. “No one has a firm understanding of the risks present in the metaverse,” Mitchell says. “For now, it’s all speculative. But it’s exciting to see how the role of brokers could change and how current products could expand to create brand-new metaverse policies.”