COVID-19 Reality Check

When Americans first became aware of COVID-19 in late January, the quickly spreading coronavirus seemed far away.

The images from China—forced quarantines, vacant streets, overwhelmed medical personnel and a rapidly rising death toll—seemed chilling but distant.

Now, with COVID-19’s spread in the United States, private healthcare insurers and self-insured employers are in uncharted waters. Early issues being revealed include supply-chain vulnerabilities, potential delays in care for patients with chronic conditions, and rising employer healthcare costs.

Before the outbreak, many were unaware the United States largely depends on other countries to manufacture drugs and healthcare equipment.

Because more timely medical attention can alleviate or eliminate illnesses, delayed care results in added costs.

Data from the coronavirus outbreak will inform future recovery strategies and provide insights into the impact on outcomes of diagnostics, comorbidity, and mobility.

Caught Off Guard

Pandemic risk is generally not a top-of-mind concern. Across the country other healthcare issues occupy our attention: out-of-control drug prices, medical provider shortages, the growing number of unhealthy Americans.

While pandemics are a recognizable concern, they rank low in likelihood. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was not nearly as widespread as the Spanish flu of 1918 to 1921 or COVID-19. In 2002, SARS killed 922 people out of 9,104 reported cases worldwide and cost $50 billion, according to Metabiota, which regularly tracks the spread of more than 100 pathogens around the globe. (The CDC and the World Health Organization estimated roughly 900 fewer cases and 150 fewer deaths.) Within weeks, COVID-19 surpassed those numbers in China alone.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2020 shows the worldwide spread of infectious disease was not in the top-10 list of risks by probability. It was, however, ranked as number 10 for impact, according to the report, released January 15. Actuaries and risk managers saw risk somewhat differently, ranking pandemics and infectious disease number eight among top emerging risks, according to preliminary results of the 13th Annual Survey of Emerging Risks. In both studies, climate change ranked as the number one risk.

There have been a few voices in the wilderness trying to warn the insurance industry of a potential worldwide pandemic of great magnitude. Max Rudolph, an independent actuary who authors the Annual Survey of Emerging Risks, has been one of those voices for the past 15 years. Once called a “doomer and gloomer,” he foresaw the potential for overwhelming healthcare resources and a significant at-risk population.

COVID-19 is a quickly moving target. The outbreak dynamic and spread of COVID-19 is changing so rapidly, says Cathine Lam, a senior data scientist and associate actuary for Metabiota’s data science team, that Metabiota is encouraging clients, including insurers and governments, to focus on the modeled near-term forecasting. “Long-term predictions could lose predictive power due to improvements in testing diagnostics and changes in reporting,” Lam says.

Healthcare Supply Chain

COVID-19 is revealing startling vulnerabilities and teaching hard lessons concerning healthcare delivery in the United States. The shortage of medical personnel has been a known public concern. What Americans did not generally know was that the United States largely depends on other countries to manufacture drugs and healthcare equipment.

“With just-in-time inventory, there is no incentive to build redundancy into the system,” Rudolph says in reference to the lack of medical equipment and supplies on hand. “The lack of a national stockpile really showed up with this pandemic, and my hope is it will be addressed.”

Other countries with more experience dealing with outbreaks demonstrated that preparedness makes all the difference. “Asian countries, which have had to deal directly with other coronaviruses such as SARS, were better equipped to handle a pandemic,” Rudolph says.

South Korea learned its lesson in the aftermath of the 2015 outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Four South Korean companies began manufacturing COVID-19 tests based on World Health Organization guidelines, and South Korea was able to test 20,000 people a day and flatten the curve. Meanwhile, Italy missed the opportunity to flatten the curve, leading to more than 18,000 deaths by early April.

Like Italy, the United States lacked sufficient tests to identify and manage the spread of COVID-19. Since tests were limited to seriously symptomatic cases, those with asymptomatic or mild cases are unknown. “We have no idea how prevalent it is in the community,” says Rebecca Owen, a health consulting actuary for HealthCare Analytical Solutions who tracks animal-sourced and other diseases.

The Associated Press reported that shipments of hand sanitizer, testing swabs and N-95 masks were also diminished when the Chinese government demanded the supplies be held up for its own country.

The drug supply chain is also affected. In March, India announced it will not be exporting antibiotics like neomycin, which fights intestinal bacteria, and clindamycin. The latter drug, which is on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines, treats upper respiratory and bone- and joint-related infections. In March, both antibiotics, in specific forms, were added to the long list of medication shortages identified at drugs.com.

Delayed Care

COVID-19 will challenge local healthcare systems differently. “Places which have an older population will have higher need for care due to the age slope of COVID-19,” Owen says. Rural areas will be particularly hard hit, she says, due to distance, population demographics and a scarcity of hospital beds, particularly ICU beds.

Healthcare plans will need to be prepared for covering elective or non-emergency medical services placed on hold. “We saw this after 9/11,” Owen recalls, when it took about two to three months to catch up and expenses increased in the fourth quarter of 2001.

Because more timely medical attention can alleviate or eliminate illnesses, delayed care results in added costs. Examples include screenings for cancer or HA1C testing for diabetics, Owen says. COVID-19 will also reveal how stress and worry impact other conditions. “We don’t understand entirely how people with immune deficiency chronic disease will do with the stress,” she says.

The impact of COVID-19 may exacerbate mental health conditions with far-reaching consequences. Owen says social isolation, fear of survival or inability to pay bills can lead to an increase in depression, opioid use, alcoholism and suicide. “Health plans can think about how they can bolster their care for SUD,” she says, referring to substance use disorders. “For example, providing access to telehealth or offering counseling services in more public places like stores.”

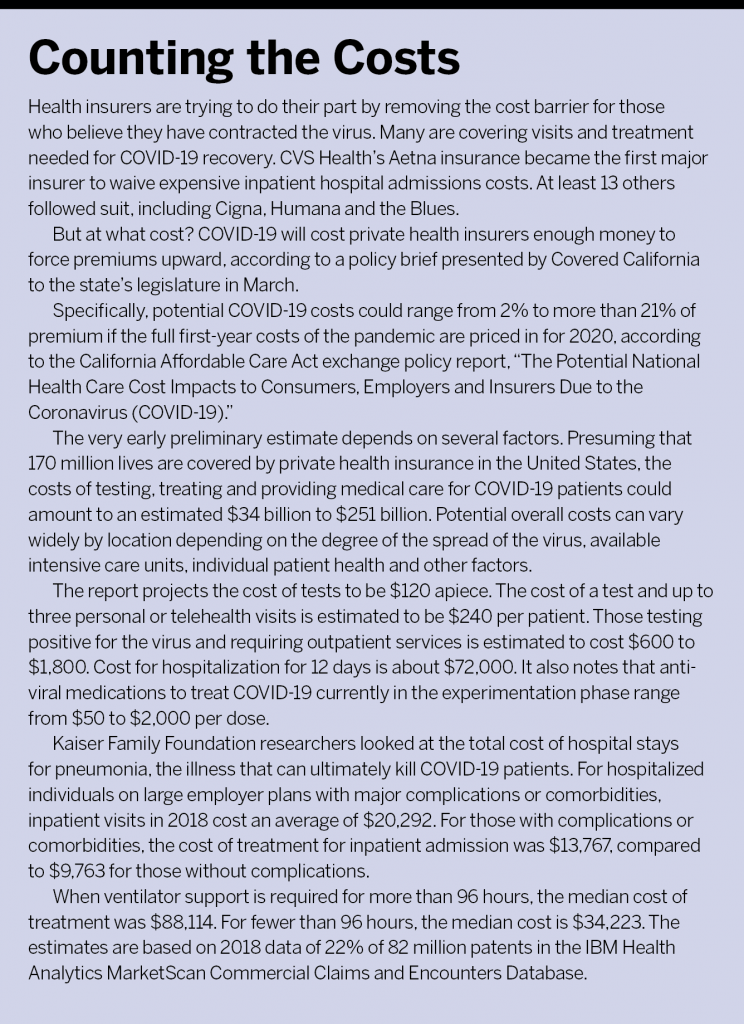

Coverage Costs

Before the coronavirus came on the scene, the United States was already showing signs of economic vulnerability and decline, says Rudolph, who specializes in enterprise risk management. “We are now seeing from reports coming out that the loan delinquency ratio had started increasing before the pandemic started,” he says.

The United States already had “loose fiscal and monetary policies” and a high debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio—“above what was historically sustainable,” Rudolph says. And since the country has a high debt load, the first round of stimulus bills is pushing the ratio up another 10% to 15%, introducing the risk of stagflation.

Self-insured plans will also be affected if the economy does not bounce back soon. Stop-loss premiums are increasing from 10% to 20% annually, according to the 2019 Aegis Risk Medical Stop-Loss Premium Survey released last August. The rise in stop-loss premiums is due to several factors, which together cause leverage trend increases for employers, says Ryan Siemers, founder and principal of Aegis Risk, which specializes in stop-loss coverage.

Siemers advises his self-insurance clients to evaluate the rising cost of claims and consider periodic increases in stop-loss coverage deductible levels to determine whether it’s more cost-effective to incur higher claim exposure or pay higher premiums for stop-loss coverage. Employers with employees on temporary furloughs due to COVID-19 are continuing healthcare coverage, he says, and should notify their stop-loss insurer of any related plan eligibility revisions to avoid coverage confusion.

“What COVID-19 is showing,” Rudolph says, “is that the healthcare system in the United States needs to be more resilient. It means building redundancy into the system, maybe extra workers, masks, ventilators, perhaps stockpile regionally.”

Metabiota’s Lam also notes that building resiliency includes collecting the best data possible. She says data from the coronavirus outbreak will “inform recovery strategies for the future, including diagnostics, comorbidity, and mobility data to estimate the impact on health outcomes.”

Resiliency also comes from more investment in a healthy public. “Everyone benefits when we have a healthy population,” Owen says. “Private insurers, employers, citizens, government. So it is in our best interest to support meaningful and effective public health initiatives now, just as it was in the past when public health attacked cholera outbreaks in London or polio in the post-war years.”

Just as prior generations left behind knowledge to benefit future generations, learning and acting on lessons from COVID-19 will benefit those to come.