Same Treatments, Dramatically Different Costs

Oakes discusses a new analysis of the cost of healthcare procedures ranging from colonoscopies to coronary bypasses in both hospital and non-hospital settings.

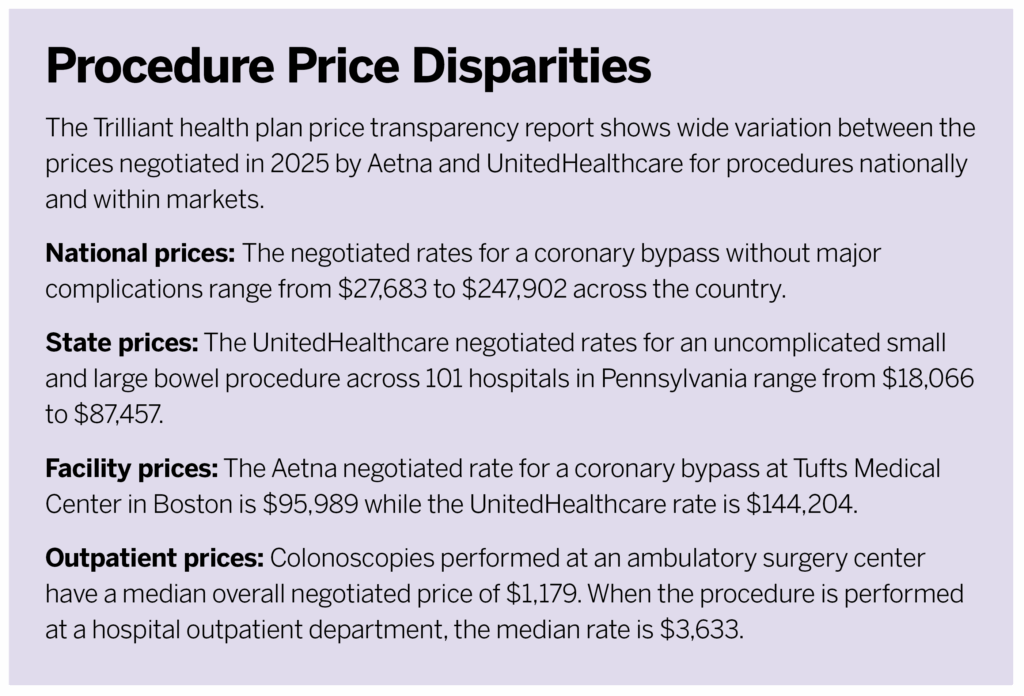

The report, from healthcare analytics and research firm Trilliant Health, finds that prices negotiated by Aetna and UnitedHealthcare for the same treatment can vary by thousands, tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of dollars based on facility or location around the country.

I don’t think a stakeholder like an employer necessarily needs access to every single data point in order to start asking the right questions. They can read the report and use it as a foundational educational piece to understand just how much variation we’re seeing across the country, to see the wasteful spending that’s likely going on within the U.S. healthcare system. By understanding that piece of the puzzle, employers can start asking benefits brokers and other folks across the health economy to start sharing more information with them about the sort of value that they’re providing to their employees.

Employers can begin to understand within their markets who the high- or low-value providers are, generally speaking. In most markets, we tend to see there’s just a handful of high outliers [facilities that charge much more for services than others in their market]. And there actually could be a strategy where, so long as your employees avoid a few problematic, very high-priced, average-quality providers, that could be one way to improve care value.

We also think that, by arming employers with the knowledge that rates vary in this way, they can begin asking tough questions to the folks that help them administer their benefits. They can start holding them accountable by ensuring they’re steering their employees towards the highest-value providers in their market. Employers can either start directly working with the data themselves or start asking the people who are helping them buy benefits if they are bringing high-value providers to the table in the networks they are setting up.

They are a huge stakeholder. Healthcare spending in [the U.S.] system was about $4.9 trillion in 2023, and employers were responsible for 30% of all that spending. That’s more than $1.4 trillion.

Employer-sponsored health insurance is considered a welfare plan under ERISA, so employers have the fiduciary duty to be administering benefits solely in the interest of participants and beneficiaries. An important piece to all of this is that, before the 2020 Transparency in Coverage final rule, information on negotiated rates was really hard to get your hands on. This was because of federal antitrust laws and different clauses included in these commercial health plan contracts. Though this information is hard to access it is technically publicly available. It implicates the fiduciary duty of those employers, and they need to be using this information to help make informed business decisions for their employees.

I would say the theme is that a market with proprietary prices is doomed to fail. We don’t see a relationship between price and quality. And when we see huge variations in negotiated rates across the country, while concerning and problematic and shocking in some ways, I also think it’s not surprising. We do really hope that this data can shift the pendulum where all these different players will start competing on things like price now that they know that people have access to this sort of information. They need to make sure they’re actually providing value to the healthcare consumer, which we think is employers—because of the way they administer benefits—but also, most importantly, to patients.

I do think during the last five to 10 years, a lot of the price transparency efforts have put the onus on patients or employees to be shopping for their healthcare services with a handful of different tools. I don’t think we’ve seen that be hugely successful. And I think that the extent of the problem that we reveal in this report mandates much broader systemic change, rather than expecting employees to shop their way out of this problem. If just those top 10% of the most expensive providers across the country reduce their rates to the market median, that would have a huge impact on overall healthcare spending.