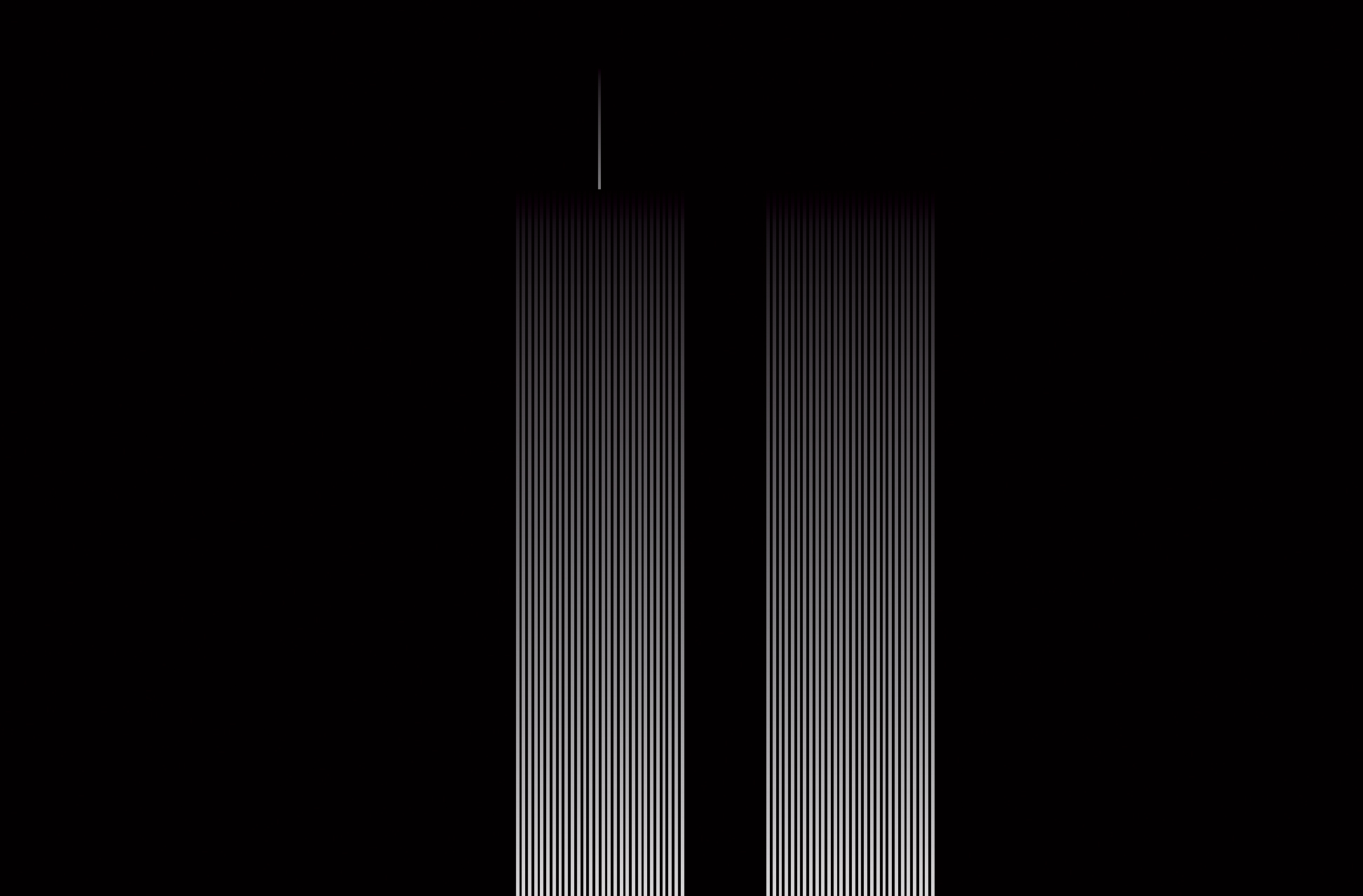

Reflections on 9/11

On Tuesday, September 11, 2001, in a span of 100 minutes, a group of al Qaeda terrorists hijacked and crashed four commercial airplanes in a coordinated attack on the United States. Nearly 3,000 were killed and thousands more injured.

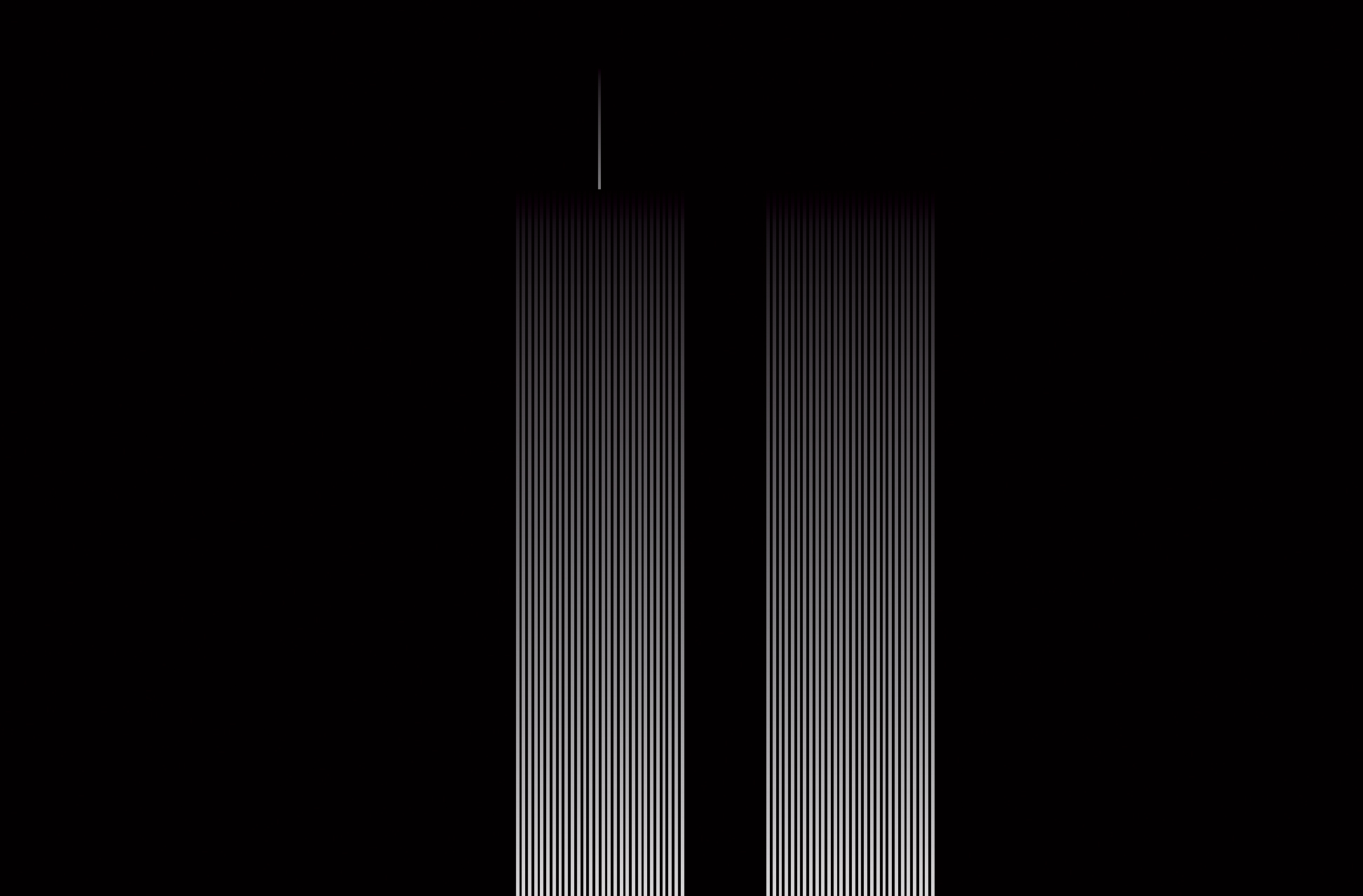

In New York City, American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175 were flown into the World Trade Center, killing 2,753 people inside the complex and surrounding area.

The subsequent collapse of the twin towers, two of the world’s tallest buildings, led to the destruction of 26%, or 31 million square feet, of all the office space in lower Manhattan.

The 9/11 terror attacks were the deadliest ever to occur on American soil, with 2,977 innocent lives lost, including 295 employees and 63 consultants from Marsh & McLennan and 176 employees of Aon.

9/11 is one of the largest cumulative claims payouts in global insurance history, producing insured losses of about $32.5 billion.

The attacks lead to fundamental changes in the way insurers operate, including the underwriting and pricing of terrorism risk.

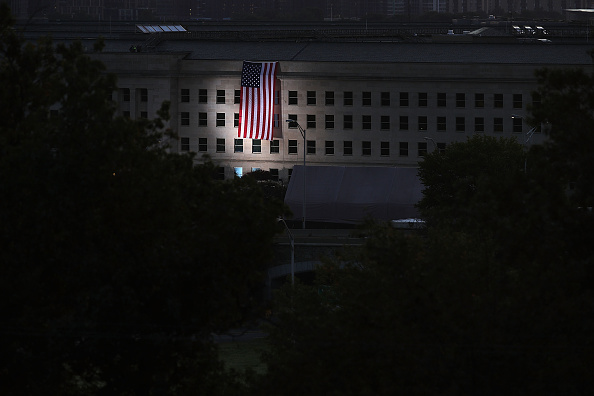

At the Pentagon in Arlington, Va., 184 people were killed, including 125 servicemembers and civilians inside the building and 64 (including six crew members and five hijackers) aboard American Airlines Flight 77. The fourth plane, United Flight 93, crashed in a Shanksville, Pa., field and was the only hijacked aircraft that failed to reach its target that day. It was less than 30 minutes flight-time from its likely target—the White House or U.S. Capitol building—in downtown Washington, D.C. It is widely believed that United 93 passengers and crew, informed about the other attacks in communications with loved ones via cell phone during the hijacking, heroically fought to take the plane back. All 33 passengers, 7 crew members, and 4 terrorists on board were killed.

The insurance industry was accountable for 9/11-related claims estimated at $32.5 billion, including property, business interruption, aviation, workers compensation, life and liability losses.

But even more devastating to the industry were the lives lost. American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower between the 93rd and 99th floors. Marsh & McLennan offices spanned the entire impact zone. United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower between the 77th and 85th floors. Aon occupied floors 92 up to 105, above the impact area.

Members of the global insurance community worked tirelessly in the days and months that followed to serve clients, tend to grieving colleagues and families, and help build the system for a sustainable future. To recognize that work, educate the younger members of our community who may not know the extent to which our industry was impacted by these tragic events, and to honor all of those who lost their lives on that day or as a result of it, we share these stories.

The Initial Strike

Tom Rodell, managing principal in Aon’s Chicago office and The Council’s 2001 chairman, was in New York City the day of the attacks.

“I remember that it was probably one of the clearest days, bright blue skies,” Rodell says. “We were starting a meeting with a number of our colleagues from the New York office and from around the country, at the Millennium Hilton Hotel, across from One World Center. The meeting could have been held in the Aon office [South Tower], but since we had so many people staying at the Millennium, one of the assistants to a colleague I worked with ultimately convinced them to comp us for a meeting room which they didn’t want to do initially. So, that was the saving grace that we weren’t in the building.”

At 8:46 a.m., American Airlines Flight 11, from Boston Logan International Airport bound for Los Angeles International Airport, crashed into the North Tower.

“It was surreal,” Rodell says. “We were in a long meeting room that faced the First World Trade Plaza. And the second tower [South Tower] was a little bit off to the left, you couldn’t see it as directly. But in any event, we heard the plane and it was just a very loud, tremendous explosion.

“The explosion and immediate fire drew everybody over to the windows. Before the second plane hit, the hotel suggested that we not leave the building because there was so much falling debris from the first tower. We still did not grasp the magnitude of what was going on.”

“As a private pilot who has flown into New York’s airports quite a bit, I knew there were no traffic patterns that would have a commercial airliner fly south in that direction. And not knowing that there were any other planes involved, [we were] trying to figure out how a plane could have flown into the World Trade Center.”

At 9:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 175, from Boston Logan, also bound for Los Angeles, crashed into the South Tower.

“When we heard the [second] explosion and saw all this debris come out of the second building, [we knew] that there had been another plane. But because of the angle, we had no ability to see that a plane was coming. And even though we weren’t sure what it was, that was the point where we knew we needed to get out of the hotel.”

At 9:37 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77, from Washington Dulles International Airport, bound for Los Angeles, crashed into The Pentagon.

Joel Wood, The Council’s senior vice president of government affairs was in the association’s Washington, D.C., office that morning with other Council staff. The office is located at 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, halfway between the White House and the U.S. Capitol building.

“I was in the office,” Wood says, “and Barbara [Haugen, a Council senior executive] told me that a plane hit the World Trade Center. Your first thought is that some small private plane had an accident. And then Dana [Wood’s wife] called me because she was only a few hundred yards away from the Pentagon on [Interstate] 395. She didn’t see the actual plane hit the Pentagon, but she saw the mushroom cloud go up and told me that the Pentagon had been hit.”

Watching the images of the first tower being hit, “there was a sensation of mortification based on the fact that I had been in the Marsh offices on the 100th floor only three months earlier. And because the Trade Center had been bombed in 1993, I remember thinking then that this has got to be the most secure building on Earth because the terrorists had already tried to take it down. The security procedures in place—you had to be on a list, they gave you an ID with your image on it, and there was some elaborate check-in process. So I was highly aware, and extremely frightened, and the toll indeed was horrifying.”

Just before 10:00 a.m., security officials in Washington, D.C., received reports of another hijacked aircraft en route to the nation’s capital and began evacuations of key buildings. At 10:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 93, from Newark International Airport, bound for San Francisco International Airport, crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Officials speculate the target was either the White House or the U.S. Capitol building, although the ultimate target has never been confirmed.

“I actually had a cousin visiting in town from Nashville, and she was on the Capitol grounds about to take a tour when they evacuated everyone; it was ants pouring out of the ground,” Wood says. “I don’t think it’s ever been firmly established that that plane was headed for the Capitol but it makes all the sense in the world. The plane that hit the Pentagon first circled the White House, which is a more difficult target. I think the assumption that everyone has is that that plane was headed for the Capitol.

“I would like to think that if there’s another major attack on the country that there’s a better plan for Washington, D.C., because people immediately all spilled into their cars and those cars didn’t move for hours on end.”

Back in New York, Rodell and his group made their way down Fulton Street to the South Seaport.

“We were down there just trying to figure out what to do next,” Rodell says. “When the Second World Trade Center collapsed, there was a fairly significant debris cloud that came over where we were. At that point, a lot of us wound up going different directions. Every street that you looked down, there were just throngs of people moving up Manhattan or across the bridges going over to Brooklyn.

“The big issue was probably the first couple of hours when you kind of knew what was going on, but you couldn’t get any calls through. So nobody knew exactly where you’re at, whether you’re in the building, not in the building. It certainly was an issue for my family. Ultimately, one of the people I was with was able to get through to their assistant, and they provided a list back to Chicago of all the people they were with, and that was the first way my wife and kids knew that at least I was OK.

“[At Grand Central], they were just filling up trains and running them out. So we wound up going on the line that goes north to Westchester [County, N.Y.]. I do remember when we were walking up right next to the East River and the expressway, there was just one firetruck after another with school buses of firefighters and police cars.

“We ultimately got to Westchester and [heard] all the air flights had stopped. We were able to get a rental car and wound up at the Aon office in Greenwich, Connecticut. And then I was able to get a hotel room where I could stay indefinitely, which I did, because I really didn’t know where I was going or what we were going to do.”

Grieving, Questioning, Serving

“There were a lot of colleagues in our New York office who needed support,” says Rodell. “I’d also like to recognize that Marsh & McLennan was in the first tower and they lost more people than we did. So, we were ultimately going through a lot of the same things… You go through this really with the help of a lot of people, because there isn’t any single way to do it. Aon rose up to do what it had to do. We set up grief centers, we had counselors available, we set up a call center in Chicago, we made certain that the families didn’t feel that there was something that they needed that they weren’t getting.

“We’d never been through something like this where not only did we lose a number of colleagues and then also not having whatever was in the building—all the computers, everything else, just trying to figure out how do we ultimately regroup. I stayed in New York for probably three or four weeks working with families and colleagues. It was as intense and emotional a time as I’ve ever been through.

“People really stepped up. The senior leadership of our insurers were engaged and were willing to help out in any way they could. And we had competitors who said, ‘Let us know what you need.’ And clients, too, [saying] ‘We’ll vacate a building, we’ll do whatever.’ And, a lot of our colleagues, while mourning other colleagues, also were trying to help clients, because we had some clients who had some huge losses. So, we had people trying to do the very best they could. And a lot of understanding clients knowing that we couldn’t get to our documentation or knowing that phone calls were difficult to return. We were always able to get messages to people, but it took some time.”

Council President and CEO Ken Crerar knew the association had to do anything and everything to support its members during this unprecedented time.

“I remember talking to Tom and I was in shock. There were a lot of discussions with people about what to do. Out of respect as well as everything else. It was a moment in time,” Crerar says.

“We just stepped into, ‘what do our brokers need?’ They needed information on the stability of the industry, and they needed it quickly. Was the industry going to survive? Were there going to be markets? I wanted to know what appetites were, what regional stuff was going on. People were desperate for information. And so we were on the phones talking to everybody we could.”

With daily emails and a conference call series convening broker and carrier CEOs in major markets, The Council parsed out as much information as possible to broker members. “Everybody was trying to assess what the impact was because it was so huge and there was not a lot of information.

“We didn’t have some of the tools that we have today to analyze things as quickly. So members were struggling because they had clients wondering, ‘Was this company going to survive or not?’”

The markets had shrunk and questions remained about renewals. “The industry was pretty amazing,” Crerar says. “We kicked into gear, the industry paid a lot out and they survived it, but it took a lot. What was the appetite going forward? We didn’t know.”

Brooklyn native Anthony Scariano, now a senior executive general adjuster at Sedgwick, was home with his six month old son in nearby North Brunswick, N.J., during the attacks. He was 10 months into his role at VeriClaim (acquired by Sedgwick in 2014) and worked closely with brokers in both buildings. Scariano was ultimately responsible for overseeing a team of adjusters and consultants on a multi-million dollar claim on a building adjacent to the Towers.

“It was pretty much mayhem,” says Scariano. “A lot of the cell phone services were down in the immediate aftermath and my mind went to so many things.” After confirming his wife and sister, who were both in Manhattan, were safe, Scariano says his attention turned to “all those people that I knew who would have been in the World Trade Center. Some very good friends at Aon and at Marsh.

“As those hours passed, we were trying to find out who was in the buildings. And little by little, we were getting that information. And I think I spent five days crying and in disbelief.

“A few weeks after, we had to start focusing on claims. How do you focus in on claims when you have all this going on? I spent the next two to three months going to memorial services.

“We couldn’t get into the downtown area for at least a couple of weeks. We had to get special passes to get into Ground Zero. I handled one of the largest claims from 9/11 [outside of the World Trade Center]. The building had extensive damage but was structurally safe to stand. Half of it was physical damage, the other half was business losses—the furniture, the IT equipment, and so on. As time progressed, we were in Manhattan all the time. We would stay overnight for three, four days straight and do our claims. Then, after about a month, the environmental concerns became very, very significant. So a lot of what we were doing for the better part of a year was testing the building for environmental concerns. The insurance dispute was whether or not that building should be deemed a constructive total loss. It took about three years to adjudicate. So it was a long haul.

“The tough part for me was we were grieving. We were all grieving big time. And we were trying to do claims, even two and three and four months later. So it was really difficult. The one person at Marsh who actually brought [my] account to me, he was killed. He would have been the one I was working with. And he was not there.”

All Claims Honored

On Sept. 12, 2001, Dean O’Hare, chairman and CEO of The Chubb Corporation, announced that Chubb would honor all claims and make payments as quickly as possible, ending speculation that insurers would invoke the act-of-war exclusion after President Bush declared the attacks as such the day before.

Dan Conway, Chubb’s long-time senior vice president of external affairs, recounts his time with O’Hare in preparation for Hill visits and congressional hearings in Washington, D.C.

“I remember very clearly standing in front of The Capital Grille on Pennsylvania and 6th, when after dinner, Dean turned to me and said, ‘I want to testify.’ And, I remember the look on his face,” says Conway. “My impression thinking back on it is that at the time, he, in his own mind, felt a personal responsibility to do what he could to the best of our ability or his ability to make things right, to the extent they could be made right.

“I think the way Chubb and the way the industry responded, I think everybody took it up a notch. You saw devastation all across so many different industries and facets of life. So many people were involved. The tragedy was very complex. The response required technical, financial, and political expertise in a tragically emotional moment. But my reflection is that everybody responded very well to that crisis. That was very impressive.

“If you see Dean’s response, and then his ability to get Chubb to respond, and move all those people, it was a reflection on him taking a personal responsibility, number one. Number two, he was in a position to actually affect the action that was needed. He understood what had to be done to respond—the knowledge and the experience. He showed great empathy. He took it personally, when he saw the losses that had occurred. I think he felt a deep sense of personal loss. And he had the courage to make an executive decision, he had the chutzpah to do what he did.

“To watch all these other people respond, I think gave everybody hope, because, as is true in these major historic moments, at the time, you don’t know how it’s going to turn out. And as horrible as it was, we came out of it, but at the time, you just don’t know. So you need to take hope and inspiration from somewhere. And I think everybody inspired everybody else.”

Wood says he “can’t overstate the importance of what Dean O’Hare did in the immediate aftermath in making that pronouncement, because on the day of, the President of the United States declared the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon to be acts of war, and war is excluded from coverage. And so I think that articulating that within a week in front of the House Financial Services Committee, and underscoring what a crisis existed—because the global reinsurers universally wrote terrorism out of their treaties on September 12—showed tremendous leadership. And so everybody else in the immediate aftermath stepped up. Now, there was some litigation. I’m not saying everything was smooth, but I think that we can look back and be very exceptionally pleased with the way the commercial insurance industry stepped up in the aftermath.”

The Market Reacts

Andrew Brooks was in negotiations to launch London-based Lloyd’s Syndicate Ascot Underwriting, which was set to go to market on Jan. 1, 2002. The attacks ultimately sped up the insurer’s decision to start writing business months ahead of schedule.

“There was a complete sense of the huge magnitude of it,” Brooks says, “the terrible loss of life, how people’s families were going to be affected, and how the U.S. and the world was going to go forward. It was an unbelievably surreal time.

“From an insurance standpoint, there was a complete state of fear—were companies going to survive? Would your company survive? Everyone could see that the losses emanating from this event were going to be profound, and from that perspective, the correlations would be unprecedented.

“Unlike a severe hurricane or severe earthquake, which starts then finishes, and your frequency and severity projections are pretty predictable, or you hope they are, with 9/11, the next day you were thinking, ‘This could happen again anywhere else in the world, and at any time.’ Suddenly, when people were looking at their aggregate position it was a sense of, ‘Even if we withstand this event, we’re not going to be able to withstand another one.’ I think that led to some cynical behavior in the market, where the primary insurers started giving notice to their clients and the reinsurers made it very clear that there wouldn’t be any terrorism coverage on new business.

“There was a paralysis in the market, similar to the Stock Exchange being shut. No one was binding any risks. Ascot wasn’t in the market then, and we just said, ‘Look, we need to come to the market, and try to get our capacity in play to help people sooner rather than later.’ So we went to Lloyd’s and to AIG, our capital provider at the time, and said, ‘We think this would be a good opportunity to help clients, customers, and actually get some positive news into the insurance sector.’ And it was well received on both sides, so we agreed to start writing earlier.”

The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act

As the market recoiled in fear of the risk, Congress and industry advocates began to work toward a public/private solution that would enable business to be covered for terrorism risk.

“It was chaotic,” Wood says. “I’d like to say that this is an example of the industry coming together and working toward a resolution but it took a long time. It wasn’t quite a circular firing squad, but there were very different views among the stakeholders as to how to construct something like this. And there was no real template for it. Initially for a period of several months, the thought was that the U.S. should develop something along the lines of PoolRe, but PoolRe was based on geography. And ultimately, the decision was that geography shouldn’t be the only factor. That risks of global terror are as vast as the imagination can go.

“[TRIA] was where the expertise of our members was essential, and I was bringing them in constantly.”

Wood consulted with [then] Marsh CEO Jack Sinnott as well as an Aon executive from London who was one of the architects of PoolRe. “Just non-stop going to member after member of the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee, key staffers and the members directly, when they were looking at that construct,” Wood says.

“It was a time when we had unique credibility, just based on our member firms being the brokers for the clients who had gaping needs, and in the relationships with the insurers to help develop a construct for them that would work for everyone.”

TRIA was passed in 2002, creating a shared system of compensation between the federal government and private insurance industry for certain insured losses resulting from a certified act of terrorism. Since its initial enactment, TRIA has been revised and extended four times—the most recent reauthorization in 2019 is slated to expire December 31, 2027. In the 19 years since Congress approved the law, not a single act of domestic extremism, including the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, has qualified as a terrorist event as defined by TRIA.

“The congressional response did evolve relative to the private/public nature of it,” says Wood. “There were legitimate concerns over the scope of the federal role in it. But I think that those have been largely mitigated based on the growing skin in the game that has evolved in the decades now since 9/11. And, then there has been some private additional capacity that people have been able to access. And those were products that were developed and marketed almost exclusively by our member firms. And all of the market surveys that we’ve done in the ensuing decades have shown good stability in that marketplace.”

Leadership Lessons

It has been 20 years since these events occurred. Our leaders reflected on what they have taken away personally and professionally, and they sound the call for lessons to be internalized and acted upon.

“Our major members lost so many employees, and to struggle through all the decisions that you have to make, and to have a chair who is in the middle of it, it was a rough time,” says The Council’s Crerar. “Tom [Rodell] played a role in this, as did the rest of the leadership. [The lesson is] to stay calm. It’s to calm the waters so at the same time you can evaluate what’s going on.

“One of the things I learned from it was that what our members need most is information, and they need quality information,” said Crerar. “And that’s what we curated. And people were desperate for it. Not that newspapers and journalists weren’t doing their job, but they needed information around the industry. And that’s what we did.”

Scariano, now at Sedgwick, says, “I certainly learned to listen more than I talk. I learned that, personally, you have to really put things in perspective. You try to say that to yourself every day of your life, right? You know, the stuff that we do every day doesn’t really matter compared to all these people who were killed in an instant. So there’s that personal part that is there.”

For Brooks, from Ascot, “The events taught me that you’ve got to be bold. It would have been very easy to retreat into your shell, not coming to the market early, not try to help write terrorism business. Being bold was also important for staff and customers who were looking for certainty—I think if they see that you’re confident, and trying to get on top of difficult issues, then it gives people a willingness to follow you during uncertain times.

“I think the other thing it taught us is that you can’t have ambiguous policy language or uncertainty. One of the big issues in the market became whether the World Trade Center itself was one claim or two claims—was each building a claim or was the location one claim? The wording hadn’t been agreed to, and from this, contract certainty was a big issue. However, a few years afterwards, around 90% of policies then had the wording agreed to prior to attachment, which I think was a big step forward for the market.

“The events also produced more market and intercompany discussions about coming together on product innovation and getting capacity together to help with specific initiatives. I think this was something that really spawned from that period and we’re reaping the benefits now—we collectively had to innovate to develop new policies, new products, wordings and address issues—it required companies to stop being competitors and think how we can work together as an industry.

“You realize that these events can happen—systematic risk can happen—and you always need to be thinking about what the next one is going to be, because you don’t want to get on the wrong side of it,” continued Brooks. “It taught the whole industry that we were all grossly underprepared. There had previously been an attack on the World Trade Center—Al Qaeda was a known movement. We’d had all the incidents in Nigeria with the U.S. embassies. And still, we all thought, ‘Well, you know, if it’s going to happen, it’s going to be an event that’s controllable.'”

“Unfortunately, it’s human nature to learn the same lessons over and over again,” says Chubb’s Conway. “Even if we are aware of a risk and the possibility of it happening, whatever it is, it’s often the case we don’t do the things that we know would be necessary to minimize the losses. Prior to 9/11, there was an attack on the World Trade Center. Before the Great Recession, the warning signs were there, some people warned but the politics were such that nobody wanted to do anything about it so you had a catastrophe. There’s Hurricane Andrew, there’s 9/11, there’s the Great Recession, and most recently, the pandemic. People know, people understand. But for whatever reason, the inertia is so great that not enough is done beforehand to mitigate or minimize the risk.

“We’re now facing climate change and the cyber situation. We’ve been talking about (that) going back decades. But have we taken or are we taking the necessary steps to really prevent a catastrophe from happening? And if something did happen, do we have the wherewithal to respond? Do we have the reserves, financial reserves or other kinds of backstops, redundancies built in to minimize any kind of loss? And the answer is probably no. So my fear is that maybe it’s part of human nature, but society, government, we all keep making the same mistake over and over again.

“Now, for example, with climate change, with cyber, we have an opportunity. We shouldn’t keep doing this over and over again, we shouldn’t keep making the same mistakes,” says Conway. “Going forward we should prepare better. We need to better manage knowable potential catastrophes.”

Rodell says, “It’s hard to measure how strong your leadership team is until you have an event like this that really presses people on all sides. Losing colleagues and making certain that we were able to be supportive to families and to attend the memorial services.

“What struck me was the human nature of all this. Realizing that, you just never know. I think one of the things I took out of it was to try to live and not put things off … and to be as open and empathetic to people as I could. And I also felt that helping provide resources to people, whether it was financial or psychological, were all critical things that the families needed.

“We also certainly learned the value of planning for disaster events. We didn’t have any computer equipment, not a piece of paper left. So you learn what it is you need to do. How will you get ahold of people? What type of recovery systems do you have? You learn what some of the weaknesses were in some of the disaster plans, because a lot of times you practice these things but you never really get to do them in real time. And this was real time.

“There’s no way we could have managed through this without discipline and empathy, and without the support of the insurance industry—insurers, other competitors, our clients.

“It was an honor to lead The Council,” continued Rodell. “We were at the center of all this, not only from the colleagues that were lost, but also, as an industry. I think the industry did a really a great job.

“But it is one of those events that you’re certainly never going to forget in your life, that’s for sure. It’s life shaping.”