Blind Ambition

As a CEO, passion for the business can be a beautiful thing. But when that passion extends to being engaged in every last detail, things can get ugly.

“I’m not sure exactly what the turning point was,” admits Adam Bruckman, president and CEO of OneDigital Health and Benefits. “But as the company grew larger, it just became impossible to keep up with this growth and still stay involved in every aspect of the business.”

A blindspot had been unveiled. Bruckman recognized he wasn’t willing to delegate. He felt if he didn’t do it himself things wouldn’t be done to his satisfaction.

“Essentially, I was worrying way too much about the small stuff rather than developing my team and trusting this team to help lead and develop the business,” he says.

Fortunately, one of Bruckman’s strengths is a willingness to listen and take feedback. And after hearing the same encouragement to focus on the bigger picture “over and over again,” he finally began to do just that.

“Now, we work regularly with our leaders on building out their teams, delegating more of the tactical work and focusing their time on high-value and strategic activities,” he says. Recognizing and working through that blindspot ended up strengthening not only Bruckman but also the company as a whole.

The most challenging thing about blindspots is that, well, we tend to be blind to them.

But as Bruckman and other leaders can attest, taking the time to honestly explore one’s own strengths and weaknesses—even if takes others helping us recognize what they are—is about far more than personal growth.

The Leadership Literary Landscape

In recent years, a handful of new and updated business books have tackled the balance of strengths and weaknesses and their impact on leadership in varied ways. Robert Bruce Shaw’s Leadership Blindspots describes the blindspot as an “unrecognized weakness or threat that has the potential to undermine a leader’s success.” This might be related to one’s own beliefs and behavior, the capabilities and motives of the team, the capabilities and culture of the organization, or the trends and competitive threats in the industry. But not all blindspots are bad; according to the author, they can be adaptive

and helpful.

Unique Ability 2.0: Discovery–Define Your Best Self by Catherine Nomura, Julia Waller and Shannon Waller is based on a concept by Dan Sullivan, co-founder of Strategic Coach. It focuses on finding the very best version of oneself by exploring innate uniqueness, passions, talents and life experience.

“Because you use [unique ability] so naturally and willingly, it’s constantly evolving and improving as you move through life,” the authors say. “When you give it room and focus on it, that evolution speeds up, and the value you create for others increases, as do the rewards.”

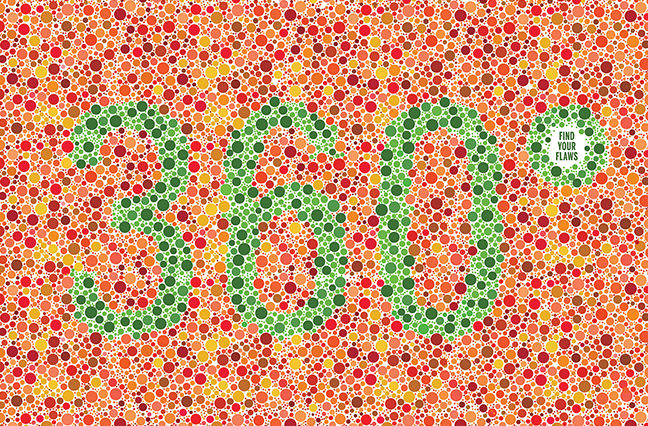

The long-standing model of the Johari window helps individuals understand how they relate to themselves. And the tried-and-true 360 Degree Feedback process is also an effective tool.

However, no leadership discussion is complete without mentioning the celebrated business management book First, Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently, which was expanded and re-released last year.

Jim Harter, Gallup’s chief scientist of workplace management and well-being, has been involved with Gallup research for more than 30 years, including the studies that led to the initial publication. The work focuses on strengths-based leadership, a concept Harter still finds often misunderstood.

“The approach, which we’ve found to be extremely effective, doesn’t imply you shouldn’t know about or even think about weaknesses,” he says. “The goal is to put employees in positions where they can spend an abundance of their time doing what they do best, knowing they’re still going to have to do some things they don’t love to do. But it’s also becoming aware of weaknesses so you can make those weaknesses irrelevant by partnering with the right kind of people, building the right kind of teams over time, and designing jobs where people can leverage who they are rather than who they aren’t.”

That requires self-awareness on all counts. The way Harter sees it, it’s essential for those in leadership to continue seeking—and exhibiting—discernment of their own strengths. When the leader is engaged, the rest of the employees are more likely to be as well.

“People assume that when you get to a higher ‘rank’ that development is no longer necessary,” he says. “It’s just the opposite. It’s continually important and necessary, regardless of the individual’s tenure or status in the organization.”

We asked some successful leaders in our industry how they continue to explore, grow and—as a result—build out their organizations in healthy ways. And we found that though they may all have different strengths and weaknesses, discovering how they can best support and position their teams for success is a true foundation for leadership.

Steve Brockmeyer, President & CEO

Bolton & Company, Pasadena, California

Self-Described Strengths: Collaborative, non-dictatorial, modeling through example

Admitted Weakness: Conflict avoidance, jumping in too quickly with “solutions”

Brockmeyer has always been a “roll up the sleeves and get it done” kind of guy. So much so that, when he was asked to take the helm at Bolton & Company in 2001, the then-president told him, “You’re doing the job anyway.”

It was the same way with his fraternity, Sigma Nu, at the University of California, Santa Barbara, more than a decade earlier. He was always “setting up, advocating for this, promoting that,” until all of a sudden, at 20 years old, he found himself running the equivalent of a small company with 70 people (an experience he still describes as the best takeaway of his college career).

He continues to prefer doing instead of just talking, he says, but over time, he has learned to step back and let others jump in first.

“I tend to default into problem-solving mode,” he admits. “Not in a dictatorial way or, ‘You should….’ But when someone asks me a question, or many times even if they don’t, I start talking. I tend to jump right to ‘solutions’ and don’t take the time to ask for more clarity or context around the issue…or what they think.”

After enough conversations ended with confusion and “Thanks, but that’s not really what I was looking for,” he began to recognize the blindspot, and he’s worked to listen more effectively and ask more questions.

“I realized a significant amount of the time the person I was communicating with already knew the answer or the path to take but maybe didn’t even realize it,” he says. “As we talk, they begin to see the path more clearly, and they are solving the issue, not me. Hopefully that gives them more confidence and education that will enable them to grow and become more self-reliant.”

Bolton & Company has invested heavily in leadership development, communications training, mentoring and other initiatives to help its 180 employees grow as individuals. A couple of years ago, Brockmeyer helped establish a “people team” led by a senior-level director of organizational development.

“Our assets are our people,” he says. “That’s all we have, and we need to do a better job with them. It’s that old story: your assets walk out the door at the end of every day, and you just hope like hell they walk back in the next.”

Personal development, he says, doesn’t just happen by chance—and he knows this from experience. Those habits of quickly taking the lead meant he didn’t receive formal training early on.

“But we’ve got young people up and coming, and I want to make sure they’re getting the support they need to be better at what they do,” he says. Brockmeyer has done his fair share of self-exploration through study, training, mentors (and learning from his own father’s example), and that practice won’t stop any time soon. It’s not just about being a better leader, he says, but rather being a better person—one more able to enrich the lives of others.

“As a leader, I’m not looking for followers,” he says. “I’m looking for people I can help….I joke I don’t know what my role in the company is. But if I do a good job at removing hurdles and roadblocks for the team…and let them do their job and give them the right facilities and support and tools and markets, if I can give them that, then I’ve done my job. That’s who I am. People don’t work for me. I work for them.”

Duane Smith, President

TrueNorth Companies, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Self-Described Strengths: Visionary, quick starter, win-win

Admitted Weaknesses: Low follow-through, impatience

When TrueNorth Companies presented its “2020 Plan” to employees in 2010, the announcement was alive with possibility. The organization was at $26 million in revenue with 133 employees and, with conservative growth of 5% organically and $5 million through mergers and acquisitions, was projected to expand to 400 people and $100 million in revenue in the not too distant future.

“We shared that with everybody and said, ‘This is an opportunity for everybody here,’” Smith says. “‘If you’re wearing three hats now, and if in the future you want to wear just one, or if you want to wear a totally different hat, we’re going to be adding 270 people minimum over the next 10 years. There are tremendous opportunities within every segment of this firm for you to grow.’ The second thing we told them was, ‘We’ll help you identify those opportunities…but you need to take ownership. Don’t wait around for somebody to say, Hey, do you want this promotion? Go for it. If you really want it, step up and ask for it.’”

The organization is already closing in on those goals, recently at 300 people and $65 million in revenue. “It worked so well that in 2015 we did a 2025 plan,” Smith says. “In 2025, we’ll be over $200 million in revenue with 900 people.”

The key to that success? Not only developing the plan but also communicating it clearly.

Easy enough for Smith, whose own personal mission statement is that he is “passionate about providing vision and instilling confidence in others to follow and succeed.” And by doing what he does best, he has helped others to do likewise.

“I have found that when I am engaged in this capacity, my energy level is very high and it is the best use of my time,” he says. He developed his mission statement using the book Unique Ability: Creating the Life You Want (also by Catherine Nomura, Julia Waller and Shannon Waller).

Smith is so sold on the benefits of identifying individual passions and exceptional talents that he estimates he’s given away more than 300 copies of the book to others.

But that’s not all: TrueNorth has developed an operating model it calls the Owners Manual, used to communicate focus and lead change. There’s an element called Structured Entrepreneurialism, which aims to balance structure with an entrepreneurial, innovative mindset, creating a dynamic culture of high-performing talent and opportunities.

“After identifying my unique ability 10 years ago, I re-engineered my life to focus on my personal mission statement and fired myself from the majority of the tasks that were not within my unique ability,” he says. “I had reached a ceiling of complexity that many of us reach throughout our career. I was the CEO at TrueNorth, but I also was the sales manager, producer, peacekeeper, you know the drill…. We were at a crossroads: sell and let someone else fix our issues or roll up our sleeves and fix it ourselves. We decided to fix it ourselves.”

As for “fixing” his individual weaknesses, Smith admits he’s from an era in which people worked harder on improving the negatives than highlighting the positives. It’s taken him decades to change his way of thinking, he says, and he has learned to do a lot of delegating along the way. That’s especially the case when it comes to his challenges with impatience; TrueNorth has grown from one project manager to six, he says, and clear timelines and progress reports help him stay calm.

Adam Bruckman, President & CEO

OneDigital Health and Benefits,

Atlanta, Georgia

Self-Described Strengths: Visionary, collaborative, inclusive

Admitted Weaknesses: Ability to delegate and stay out of others’ areas of expertise

Bruckman considered himself fairly self-aware. But over the last few years, he’s found unexpected new passion, energy and purpose by diving into something he’s long advocated to others: greater work/life balance.

Bruckman, who played lacrosse while studying economics at Tufts University, coached both his sons through junior levels. But then he was asked to become the varsity lacrosse coach at their high school, leading to “a very reflective few months.”

Yes, he leads an organization of 800 employees, one he started in 2000 at age 32. But he also knew that the shared time with his boys would be fleeting.

“I love what I’m doing day to day in my job,” he says. “But I love being with these young men, too, teaching and coaching them. It’s really not that much different. It’s about putting people in positions to be successful, finding ways to motivate them individually, and realizing some need to see a softer side and others need a kick in the butt.”

And as he invested time in doing that, he says, his time at the office has become more streamlined and efficient. He has delegated more, and he sweats the small stuff less. And the organization is all the better for it.

“As you get a little larger, you have the luxury of rounding out your leadership team,” he says. “That has really allowed me to not try to be all things to all people but to really focus on what I do well.”

In recent years, the original leadership team of three tripled, including the addition of a COO and several other executive-level positions. (Digital Insurance and its advisory arm, Digital Benefits Advisors, rebranded as a single operating company, OneDigital Health and Benefits, in August.)

“I love the people side of the business, being able to inspire folks,” he says. “That’s what I do well, and the company is best served when I focus on those things, not when I’m telling our CFO how to manage the

numbers or our head of sales how to close a deal.

But it’s been something that I’ve had to work hard on over the years, to not feel like I have to have the answer for everything.”

The company—which also has an executive vice president of culture and corporate development—offers a number of different initiatives for employees to likewise discover their unique capabilities, especially focusing on growing leadership from within. One curriculum has four levels, from the basics of interviewing as a new manager to attending leadership training at Disney Institute.

“In our industry, particularly on the agency side of the business, there just aren’t a lot of organizations putting in that time and effort,” he says. “We’ve had really great feedback, and it has been extremely valuable with retention and attracting the right talent…. We work hard on creating an environment where it’s more than just a job.”

Damien Honan, CEO

The Honan Insurance Group, Southbank, Australia

Self-Described Strengths: Motivator, ability to set and maintain culture

Admitted Weaknesses: Being too nice, forgiving to a fault

Honan has learned an important lesson about decisions: as a leader, he’s often judged as much for the ones he doesn’t make as the ones he does.

Case in point: dealing—or, rather, not dealing—with nice people.

He’s found himself hoping that nice people within the organization would “respond and make it, when all the signs are showing that their skills, efforts and contribution are not to the level we require,” he says. “That impacts the morale and culture. Other people start to feel there is one rule for them and another for us.” It shows, he says, that he’s willing to accept lower standards from some. But hoping never works, he admits.

What does work, however, is helping employees learn what their individual strengths are and, when something isn’t a good fit, helping those employees consider other options.

Honan gives the example of a particular employee in the finance department who had superior people skills but not other traits that would help him rise to leadership in that department.

“We identified that he had the skills to be a producer,” he says. It took 12 months for the transition to happen, “but his results have been outstanding. He is such a high-level producer, and his contribution to the culture of the company has been amazing. Here was someone who was in the back office and didn’t have high visibility within the broader broker side of the business, who is now front and center of that unit.”

Honan also has seen success by recruiting from outside the industry, especially from fields such as teaching (the ability to clearly communicate), science and finance (analytical thinking skills).

Honan’s father founded the company in 1964, and Damien became CEO in 1996. Since then, he has maintained his easy-going style even as the company has grown. He has learned to focus more on his ability to set corporate culture and feels less like he has to step in and do everything himself.

“It takes a while to trust,” he says. “Not trust in the sense that someone is going to be untrustworthy but more that you can trust their abilities will be able to deliver the outcomes, the results, you want. My leadership has developed in the sense of trusting the people around me to live what the vision and the goals of the company are.”

One of those goals, he admits, is to ensure people want to stay at the company for more than simply monetary reasons, that they understand the expectations of what the company is trying to achieve and feel empowered to act within that framework.

“The ultimate mantra is that we want our people to be the best so that everyone else, all our competitors in the industry, want to steal them,” he says. Even across borders.

Honan’s company is based in Australia, but that doesn’t mean he believes all the keys to business success are found there. Rather, he takes a global approach to best practices and ensures his roughly 185 employees have the opportunity to do the same.

“We invest a lot of resources, through the various programs we run, sending people overseas,” Honan says. Conferences and workshops in the U.S. and Europe may see teams of a dozen or more from Honan at a time, “and the primary reason is for our people to learn how others are operating, how they communicate, how they talk about their businesses.” (North American leaders, by the way, tend to be more assertive but also more politically correct, he says.) A number of training and development programs are available at home, too, helping employees capitalize on individual skill sets.

“You can’t make everyone the captain of a team when they don’t possess the skills to do it,” he says. But teams need more than just a leader.

Soltes is a contributing writer. [email protected]