21st Century Gerrymandering

Every 10 years, following the U.S. Census, another census of sorts determines the balance of national political power for the next decade.

It isn’t controlled by voters, but by state-elected politicians and data analysts. This process, known as redistricting, has become ground zero in the battle over U.S.democracy. Nowhere is thatfight more intense than in Texas, where Republican state lawmakers are pushing through a new map that could add five GOP seats to Congress.

Redistricting involves redrawing electoral district boundaries, typically for legislative seats like those in the U.S. House of Representatives or a state assembly. The basic purpose is to account for population changes as some areas grow while others shrink, adjusting district lines to maintain fair representation. Each congressional district, for example, should contain approximately the same number of people so that each person’s vote carries equal weight.

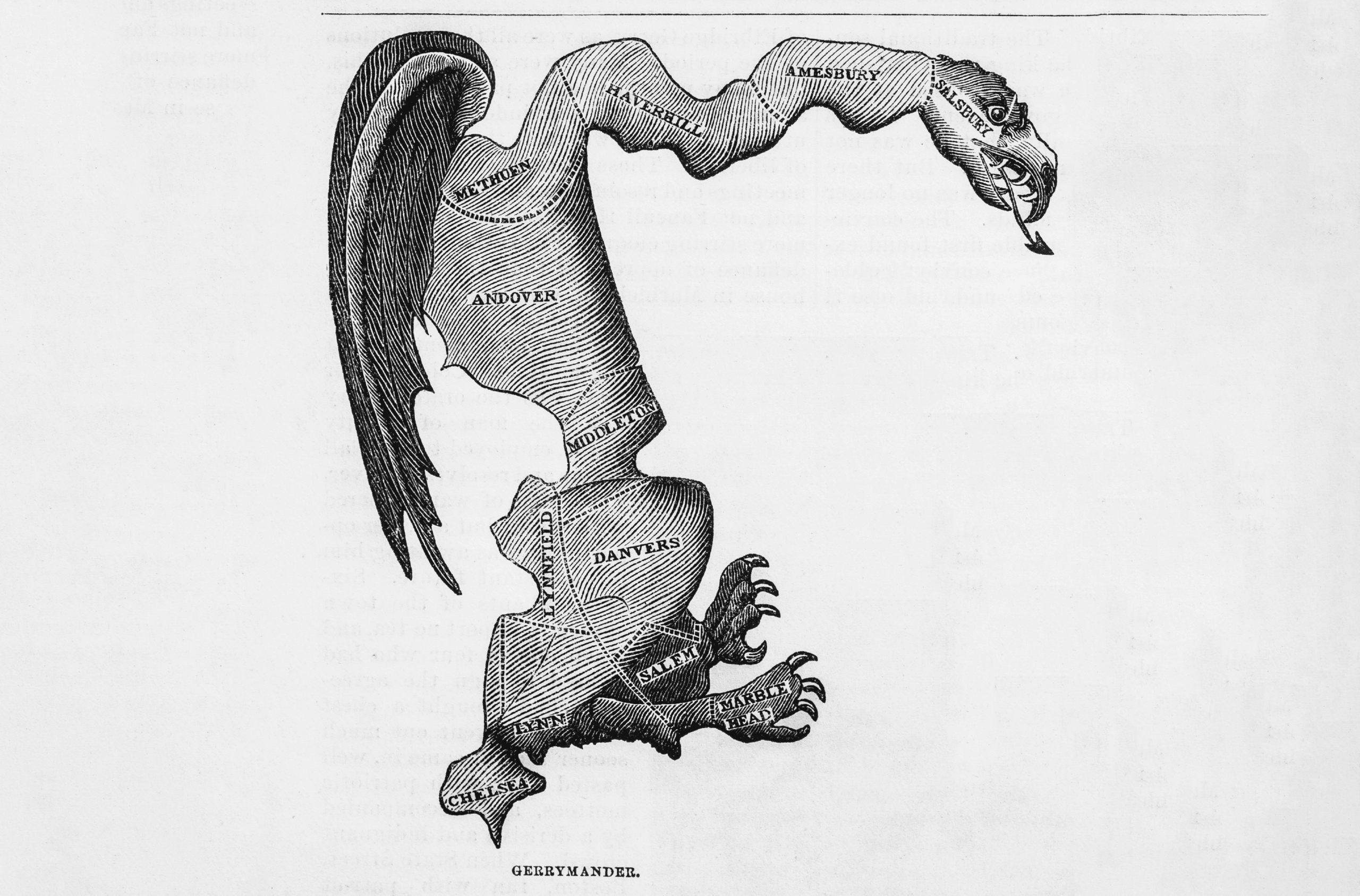

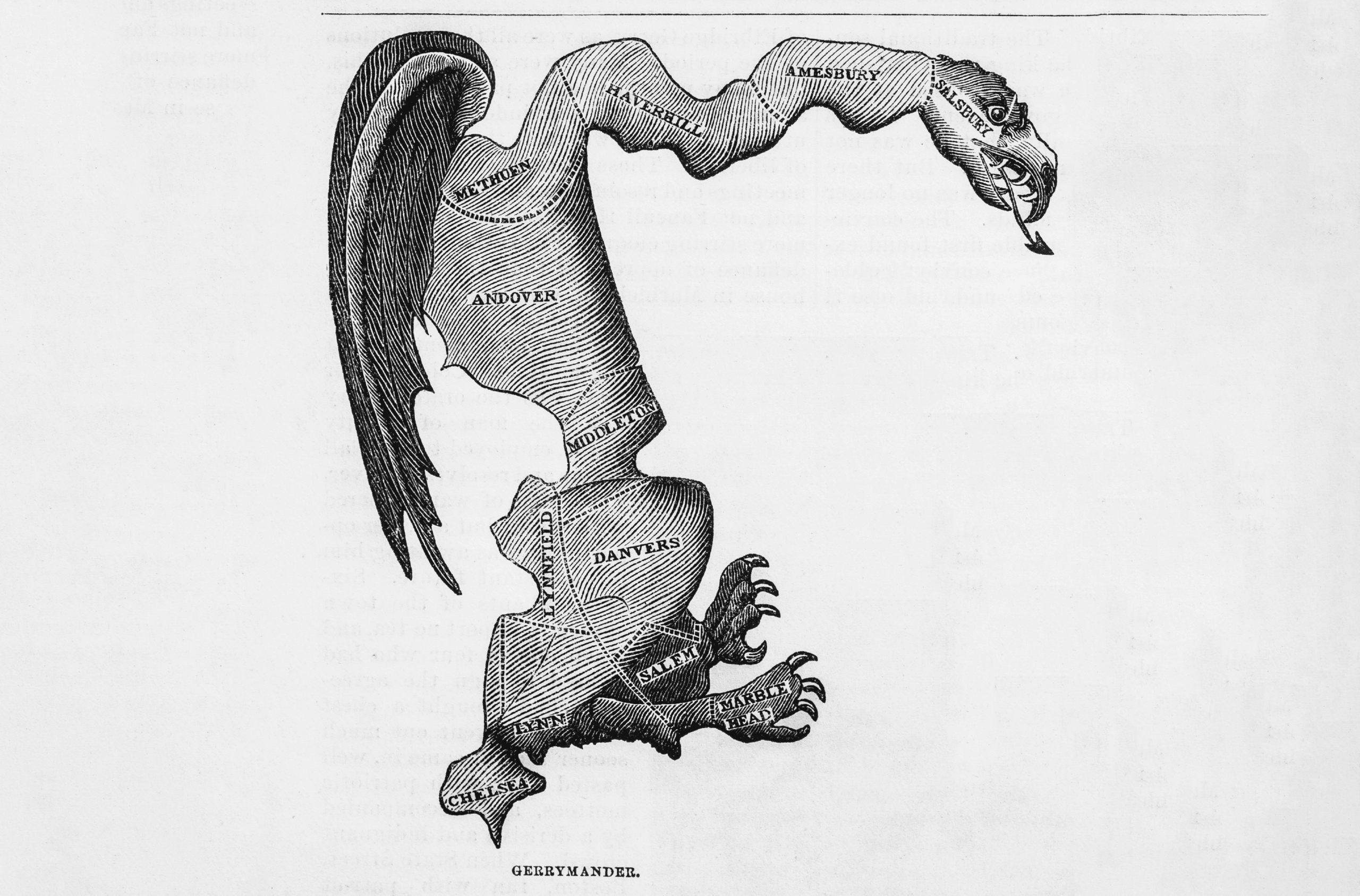

The term “gerrymandering” dates to 1812, when Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry signed a bill creating a partisan district so contorted that a Boston Gazette cartoonist famously depicted it as a salamander (since it looked like one). But the practice is as old as American democracy.

From the beginning, the Founding Fathers understood that controlling district boundaries meant controlling electoral outcomes. (Gerry, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, served as vice president to James Madison, who earlier in his career reportedly ran in a congressional district created for him so he could introduce the Constitution’s Bill of Rights.) In the early republic, state legislatures routinely drew districts to benefit the majority party, often creating wildly irregular shapes that snaked through friendly territory while avoiding hostile voters. The practice became so entrenched that by the mid-19th century, it was accepted as normal politics.

A series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1960s upended the process, most notably Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), which established the principle of “one person, one vote.” Districts now had to contain roughly equal populations, ending the skewed representation in which rural areas wielded disproportionate political influence relative to their population, often at the expense of urban and suburban areas.

But rather than disappearing, gerrymandering simply became more sophisticated. The rise of computer technology in the 1990s and 2000s transformed redistricting from an art into a science. Armed with detailed voter databases, Census data, and powerful mapping software, political operatives could now predict electoral outcomes with unprecedented precision. They could slice communities along demographic lines, move districts by individual city blocks, and engineer near-certain partisan outcomes.

The 2010 redistricting cycle marked a high-water mark for strategic gerrymandering. Republicans, having gained control of numerous state legislatures in the Tea Party wave, launched “REDMAP,” a coordinated national strategy to maximize GOP representation through redistricting. The results were dramatic: in 2012, despite receiving fewer total votes nationwide, Republicans maintained control of the House of Representatives largely due to favorable district lines.

However, frustrated by increasingly brazen partisan manipulation, reform advocates have pushed for an alternative: remove the pen from politicians’ hands and give it to bodies that prioritize fairness over electoral advantage.

Currently, 26 U.S. states have some form of nonpartisan or bipartisan redistricting commission, though they differ significantly in structure and authority.

No state illustrates the modern redistricting wars better than Texas, where a dramatic confrontation is unfolding as of this writing. In late July, Texas House Republicans unveiled a new congressional map aimed at adding five new, friendly U.S. House districts mid-decade, setting off a political firestorm during which Democratic legislators fled the state to break quorum and prevent passage of the plan. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) has sought to punish the errant Democrats even as California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) has threatened to create five new Democratic Party districts in his state if Lone Star Republicans follow through with their plan.

Legal challenges remain the primary check on extreme gerrymandering, though the Supreme Court in Rucho v. Common Cause ruled that the issue presents questions beyond the authority of federal courts. State courts have stepped into the breach in some cases, but their authority varies widely.

The Texas fight may preview the future of gerrymandering battles where lines can be redrawn when the party in power feels like it. The redistricting wars are far from over.