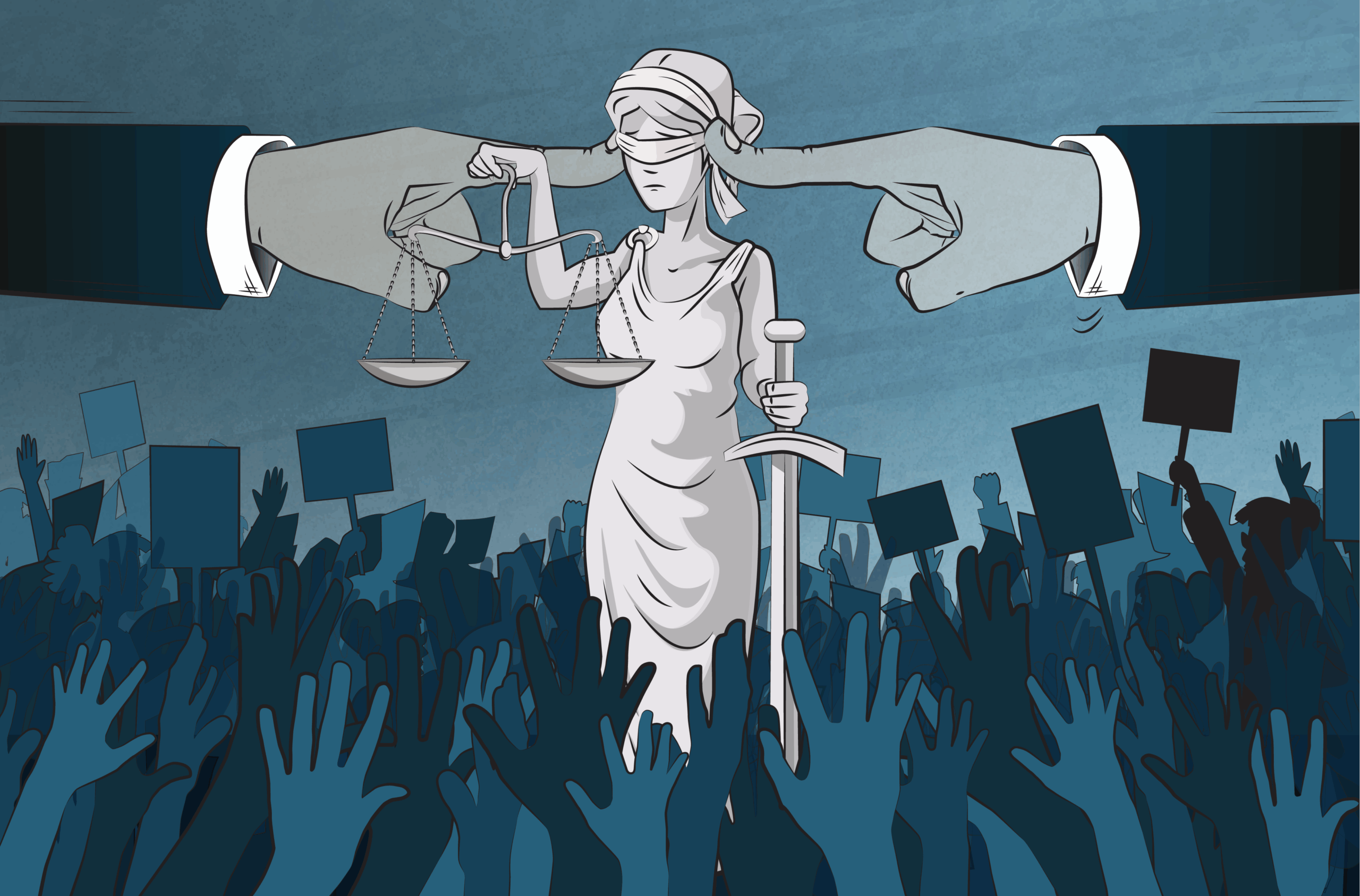

Judicial Integrity Dies in Darkness

While attending a large gathering in November, my wife and I struck up a conversation with a friend of a friend.

We quickly learned that he’s a junior associate at a plaintiffs’ attorney firm, and that his job is to identify current or former cancer patients in a poor rural county in the South where apparently the water district had been fined for tainted water.

Or something to that effect. I just remember that the lawsuit will seek billions in damages, that it’s part of a litigation finance scheme, and that his job was to lasso cancer patients or find dead plaintiffs so they (or their survivors) could get their bonanza. Assuming that happens, there would be a nice payout for the litigation financiers, who could be many types of deep-pocketed entities—hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, oligarchs, you name it.

My wife was kicking me and mouthing “Don’t say anything!” as this conversation proceeded, for fear that I would make a scene. Fortunately the kid didn’t ask what I do for a living.

Third-party litigation financing (TPLF) is just one of many forms of lawsuit abuse: frivolous and vexatious litigation, abuse of discovery, malicious prosecution, legal harassment, forum shopping, billions of dollars in plaintiffs’ advertising, nuclear verdicts. And then there’s the Reptile Theory—getting the jury to feel anger or fear about a specific case. In other words, persuading a jury to “send a message.”

Equally pernicious is the use of “anchoring.” Allen Kirsh, head of claims judicial and legislative affairs for Zurich North America, described it like this in a recent podcast: “Anchoring is indoctrinating the jury early on in terms of the value of the case. So, the way this comes about is even during jury selection, when the attorneys are allowed to ask jurors questions and a plaintiff’s attorney may ask the question, ‘Are you comfortable awarding $25 million in this case? Are you comfortable awarding $50 million in this case?’

“Their point is partly to find out if they are comfortable with that, but also it’s letting them know, this is what we think this case is worth, right? So that juror right from the very beginning, before they’ve heard a shred of evidence or even met the parties, are thinking, ‘Oh, wow, I guess this case is worth a lot of money.’”

As I’ve written in this space as recently as two months ago, legal reform will be a high—if not the highest—priority of our association in the coming year. We have teamed with the American Property Casualty Insurance Association (APCIA) and the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America in an organized effort to try to move the dial. We’ve identified states where we will have opportunities for lawsuit abuse reforms, and those where we may have to take a defensive posture. Brokers will be hearing from us about how to help achieve these legislative objectives.

Yes, agents and brokers are mostly one-off victims of lawsuit abuse (we used to call it “social inflation,” but that term made no sense to the general public). According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform, overall tort costs in the United States have eclipsed more than a half a trillion dollars, translating to about $4,207 per American household as of 2022. These costs contribute to higher prices for basic necessities and overall inflation. It is simply a major economic burden, undermining families’ financial stability and the economy as a whole. It is our problem.

“The top priority for us, by far and away, is legal system abuse reform,” APCIA President and CEO David Sampson said in a recent Insurer article. “It is the most important cost driver for insurance loss cost that exists. It’s the number-one issue that every CEO that I talk to raises with me.”

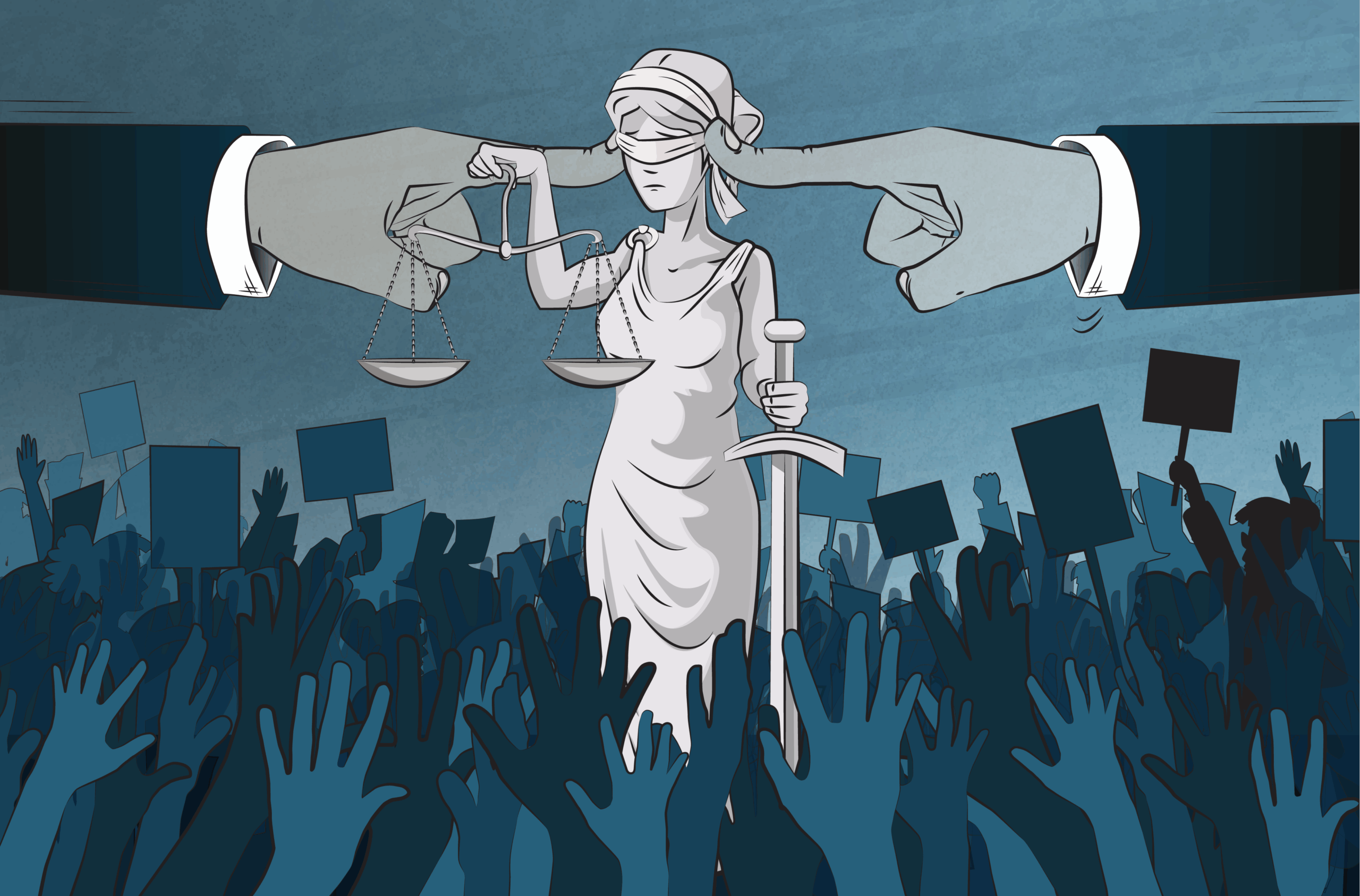

But back to our friend who’s door-to-door shopping for cancer patients on behalf of a third-party litigation financier. According to the Institute for Legal Reform, virtually all TPLF activity in American courts occurs in secrecy because there is no generally applicable statute or rule requiring disclosure. When defendants seek this information, plaintiffs resist strenuously and courts don’t typically compel its release.

“Thus, the existence of TPLF in a particular civil action typically becomes known to the court and the parties only if there is a local rule or standing order requiring it,” the Institute said in a prepared statement for a July House Judiciary subcommittee hearing on litigation financing. “Despite this secrecy, it is clear that the amount of litigation being funded by non-party investors has grown by leaps and bounds over the last decade.” In 2024 alone, 42 commercial litigation funders had $16.1 billion in assets, according to Westfleet Advisors.

Not only does this risk the integrity of our civil justice system, it raises questions about threats to national and economic security. Foreign sources can file lawsuits against American companies in sensitive industries and receive highly confidential documents containing proprietary information. As former U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland said, “By financing litigation in the United States against influential individuals, corporations, or highly sensitive sectors, a foreign actor can advance its strategic interests in the shadows since few disclosure requirements exist in jurisdictions across our country.”

Across the hallway from The Council’s offices on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., is the advocacy office of Bayer, the giant, German-based biopharma and agribusiness conglomerate. Their lobbyist shared with me recently that a jury in Georgia once awarded $2 billion to a single plaintiff on the allegation that he had been harmed by a pesticide produced by Bayer.

The guy had lymphoma. A couple of years later, his cancer is completely gone. But the verdict’s still under appeal.