The Benefits of Aging

Twenty years ago, more than one third of all employers were promising retiree health coverage to their newly hired employees as part of their benefits package. But in the past two decades, things have changed.

The cost of providing health insurance to employees has risen dramatically. Retirees didn’t used to have a drug plan to combine with Medicare. And state individual exchanges didn’t exist to cover people who retired before age 65, leaving the often-expensive COBRA as their main insurance option before they were eligible for Medicare. But even as employer retiree coverage has become more expensive, many of the gaps it filled for beneficiaries have been covered by Medicare options.

“Offering retiree health insurance is on the decline, and what is left is large companies with legacy promises,” says Trevis Parson, chief actuary for the individual marketplace at WTW. “For the most part, when you think of retiree medical plans, it’s large companies. Employers are trying to find ways to appropriately and gently remove themselves from these benefits.”

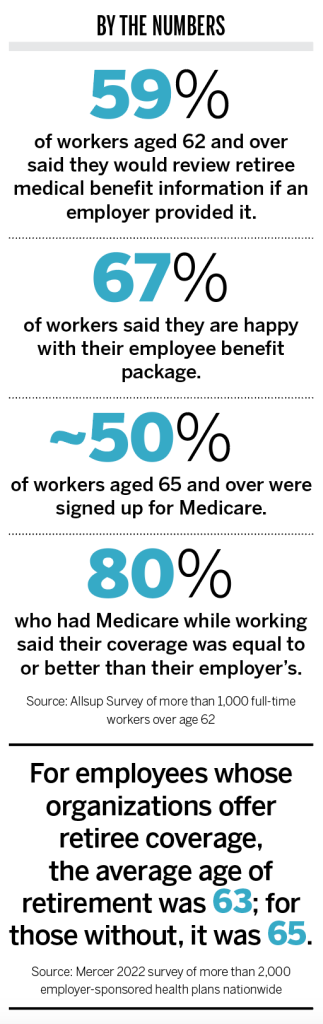

But not all employers are washing their hands of health benefits for the over-65 crowd. According to a 2022 national Mercer survey of employer-sponsored health plans, about 35% of the 2,000 employer respondents said they offer retiree health plans to at least one group of workers. Among public sector respondents, 43% provide free Medicare, and 28% offer a group health plan to eligible retirees. And in today’s insurance market, there are myriad ways employers can provide benefits, subsidies or just education to people moving from employer plans to the great unknown of Medicare.

On the Payroll

For people over age 65, healthcare eats up a large portion of their overall budgets. According to a 2022 report from the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, the median outlay on medical expenses for retirees in 2018 was $4,311. The top spenders paid between $9,600 and nearly $11,000 per year. A large part of this spending comes from out-of-pocket expenses.

Particularly after COVID, which caused mass layoffs and high medical costs for some, many people want or need to work into their later years. According to a 2022 survey of people over age 62 by Allsup, a group benefits coordination service, most respondents said they expect to work until age 71. Sixty-three percent of respondents said they were going to work later than they had originally planned because of economic or healthcare issues.

“If we think of the current workforce, many people over 65 are locked in and need to work or want to,” says Chris Maikels, U.S. growth leader for retiree solutions at Mercer Marketplace 365+. “They are hesitant to retire, because they might not have pension or medical. That’s an emerging trend: that we expect employees to work later.”

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) suggests this delayed retirement could last for at least a decade. A recent BLS report found that workforce participation rates are declining or remaining steady among people aged 16 to 74. The only part of the workforce that is expected to grow in the next decade is people over age 75—increasing from 8.9% of the total workforce in 2020 to 11.7% by 2030.

For this aging workforce, employers have to be somewhat careful in the benefits realm. Businesses can’t require or encourage employees to move to Medicare at age 65 and can’t even appear to do so. A lot of human resource personnel are expert in group plans but don’t have a great understanding of how Medicare works. And workers are often just as confused. In the Allsup poll, 44% of people ages 62 to 64 didn’t plan on signing up for Medicare when they become eligible at 65. The top reasons for the delay included not knowing if they were eligible if they were still working; thinking the coverage would not be as good as their employer’s coverage; or not knowing their options.

Sifting Through the Options

Employers can work with organizations that help people understand their options and get the best coverage for themselves and their spouses. One such group is SmartConnect, which acts as an advisor to Medicare-eligible people still in the workforce.

Human resource departments refer Medicare-eligible people to SmartConnect, which helps employees compare Medicare plans and the group plans from their employer. About 25% of the time, employees who talk with SmartConnect end up enrolling in Medicare with an advantage or supplemental plan instead of staying on their employer’s insurance, says Mark Hunter, president of Spring Venture Group, SmartConnect’s parent company. Even more would enroll, Hunter says, but some have issues, such as a spouse who needs to stay on the employer’s plan.

“People are working longer after the age of 65 and are confused about their options, so they just stay on their group plan,” Hunter says. “But more often than not, Medicare is more beneficial for them. People are often surprised they are better off with Medicare and a supplement or Medicare Advantage.”

SmartConnect gauges what is best for each employee by looking at the premium they pay for their group plan along with their exposure to out-of-pocket expenses. That gives SmartConnect a baseline for comparison. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the average monthly premium for a Medigap (Medicare supplement) plan ranges from about $100 to $250, depending upon the plan and age of the beneficiary. The average Medicare Advantage premium is $18 per month. Kaiser Family Foundation reported that, in 2022, the average annual premium an employee pays for individual employer group coverage was about $110 a month.

SmartConnect is a free service for employees, and employers pay a small fee for things like direct mail to employees, which ends up being less than $10,000 a year. Even with the fee, Hunter says, this kind of program is good for both small and large employers. (According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, employers contributed $6,584 per employee for single coverage and $16,357 for family coverage in 2022.)

Aside from potentially saving an employer money when people move from the group plan to Medicare, Hunter says, the service is valuable to help employees understand an extremely confusing market. People over 65 have an onslaught of information and advertisements coming their way during Medicare open enrollment. Hunter says people often end up disappointed to hear about benefits they saw in ads that are not available in their area.

“Medicare can’t be captured in a 30-second commercial,” he says. “This often is a two-hour conversation with our team talking about plans available for them and the different options they have. It takes that long to wrap their arms around it.”

Medicare ETC.

The number of employers who offer retiree benefits is shrinking. According to a 2022 health benefits survey performed by Kaiser, about 21% of large employers offer retiree health benefits, down from about one third of respondents in the early 2000s. Though fewer businesses are providing these plans, among those who do, Medicare Advantage is increasingly becoming the darling.

Fifty percent of large employers in the Kaiser survey that offer retiree benefits cover at least a portion of their beneficiaries with Medicare Advantage plans. This number has nearly doubled since 2017. The reason so many are moving in this direction is cost.

“In the last four to five years, Medicare Advantage has become the most prevalent strategy for employers making changes to their retirement benefits,” Maikels says. “When clients move from a fully insured plan to Medicare Advantage, they can see up to a 50% reduction in premiums.”

Premiums are lower than a traditional group plan because much of the cost is paid from the federal government’s coffers. There isn’t a lot of data on what CMS pays toward the plans, because they are private, but experts say it’s a majority, if not all, of the premiums.

Aside from cost, Maikels says, there are other attractive features of Medicare Advantage plans (as opposed to supplemental plans or traditional Medicare). One is their similarity to the employer’s group plan. Employer Medicare Advantage plans tend to be much like the plans on the open market, but they can be tailored to the needs of an employer’s specific 65-and-over population.

“There is a flexibility of design,” Maikels says. “The plans can be designed in a way that is customized to minimize disruption. Coming from a self-insured plan, Medicare Advantage can mirror—or be slightly better than—what the employee just had, providing minimal disruption for employees.”

Preferred provider organization (PPO) options that have come about in the past several years have also helped eliminate network-access concerns. National-access PPOs are available that allow people to see doctors when they travel. Prior to that, beneficiary coverage might have been restricted to doctors in participants’ local network, much like through their employer’s group insurance. Traditional Medicare allows people to see any doctor who accepts the insurance nationwide.

Medicare Advantage has also dramatically expanded its ancillary benefits in recent years, often providing well beyond what an employer or traditional Medicare offers. Some plans cover dental, vision, fitness clubs, meal delivery, in-home support, transportation to medical visits, telemonitoring and acupuncture.

Regarding Medicare Advantage, Gretchen Jacobson, vice president of Medicare at the Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based foundation dedicated to increasing affordable, quality healthcare, says, “With the large government payment and an employer contribution, businesses can put together a pretty generous set of health coverage options for their retirees. It provides more benefits than are provided under traditional Medicare and caps beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs for services, which traditional Medicare doesn’t.”

The average in-network, out-of-pocket maximum for Medicare Advantage health management organization (HMO) and PPO plans in 2022 was $4,972, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicare Advantage plans work well for many retirees, but they are not without some controversy. For example, a much-embattled change to Medicare Advantage for employees of New York City could go into effect this fall after retired city workers sued over a potential change from their Medigap plan to Medicare Advantage. The employees sued over concerns including sufficiency of the network coverage, potential higher out-of-pocket costs and prior authorization.

All these things can be issues with Medicare Advantage when compared to traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans, like group plans, perform utilization management. This means the plans can require prior authorization for some services and plans can deny treatment or increase cost sharing if they deem a service shouldn’t be covered.

The plans can also charge beneficiaries more to see doctors who are out of network. Medicare Advantage, unlike traditional Medicare, has networks of physicians a patient can see. Though the networks have expanded since the early days of the plans, there may be issues in some communities.

“It can be tricky if people are in a small town, because they usually have networks based on the county,” says Lauren Bigham, assistant marketing manager of Boomer Benefits, a Fort Worth, Texas-based insurance agency that specializes in Medicare products. “Beneficiaries should make sure there are many counties included, because they may end up not having as many providers in-network.”

Two other potential issues with Medicare Advantage plans are choice and drug coverage. In the Kaiser survey, 44% of employers that offer these plans didn’t allow retirees to choose between coverage options. Jacobson says there can be a significant difference between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage drug plans. In traditional Medicare, beneficiaries can choose between all plans offered in their area. With Medicare Advantage, retirees get no choice—just the plan chosen by the employer.

Finally, several studies have shown that the average Medicare Advantage beneficiary costs more than one in traditional Medicare. According to Kaiser, Medicare Advantage spending was $321 higher per enrollee in 2019 than it would have been for traditional Medicare coverage. This, Kaiser says, cost Medicare $7 billion that year.

Part of the additional costs are due to added benefits covered under Medicare Advantage. But “aggressive coding” in some plans has also contributed to the higher costs, Jacobson says. This has made organizations like CMS consider if there are excessive profits from these plans by the carriers.

“Anyone coming at arm’s length of Medicare Advantage plans is saying, ‘Wait, the plans have no premiums, carriers are doing well, and people are costing more than traditional Medicare… Maybe we should dig into this and understand how this is happening.’ And it looks like CMS has,” Maikels says.

While spending by Medicare might not seem like it would directly impact employers, the excess could affect Medicare Advantage in ways that employers may feel down the road. CMS created an updated risk adjustment model that will be phased in over time which will limit carriers’ ability to code conditions by range of severity, Maikels says. CMS has also reduced its funding going into 2024 and is making it harder for carriers to achieve 4.5-star and 5-star ratings (which equate to more dollars for the carrier).

“If more carriers are getting lower stars and reduced funding, there could be some short-term increases in premiums,” Maikels says. “With less funding, something will have to change, like benefits being pulled back or premiums going up. We’ll have to wait and see how it will shake out in the market.”

Even if premiums become slightly higher or benefits less robust, Maikels says, the plans’ popularity will continue to grow. If employers are saving 50% now and 25% in a few years, the added benefits and ease may keep them an attractive option for many employers wanting to move from a group retiree plan.

Less Skin In the Game

If employers don’t want to cover the cost of a Medicare Advantage plan, they have other, less expensive options. Some organizations offer subsidies for Medicare Advantage or supplemental plans. Employers can subsidize Part B premiums or Medicare Part D (the drug plan). Companies can also offer their own drug plan for Medicare beneficiaries.

With the number of employers paying the full cost of retiree health benefits on the decline, what remains is mostly larger companies with legacy promises, according to Parson. For those that are non-bargaining, some organizations even find themselves with a mélange of options based on the employee group. People that retired before 1990, when it was more common to offer retiree health benefits, may receive the benefit for life, paid for fully by the employer. The next youngest group may receive it, but the employer pays for only half of the benefit. The cluster after that may just receive $1,000 annually toward the plan.

“No one is rushing out to start new retiree medical plans,” Parson says. “But some are thinking about putting in limited benefits in a tight labor market. They may say, ‘Maybe every year you work here we’ll put money in an account, and you can use that to pay your premiums when you retire.’”

For companies wanting to get out of the health insurance game altogether but still wanting to support the health of their retirees, there has been a movement toward a defined contribution or educational approach.

One option is retiree Medicare exchanges, which work much like state health exchanges do. An employer contracts with an organization that curates local plans for its retirees and offers decision-making support so beneficiaries can choose the best option for their situation.

“There are a lot of plans out there on the market, and lots of them are complicated,” Parson says. “For people who didn’t work in healthcare and are not benefits experts, they are left asking, ‘What do I do?’ They might be left at the mercy of someone just trying to sell them a plan and make a buck.”

WTW offers an exchange through Via Benefits, where, Parson says, the Medicare plans available are vetted and include ones provided through well known groups like AARP. Employers sometimes pay a small fee for the administrative setup, but the service is free to the employee. Most of the funding comes from the insurance companies through commissions when plans are sold.

Alight is another organization that works with employers through an exchange. Andre Walton, executive vice president of retiree health solutions and absence management, says Alight works with companies in a structured way, with a detailed communications plan, to help employees move from the group to the individual market.

“Think about a retiree working for a company for 30 years and never having to make a choice in the individual market,” Walton says. “All they’ve done for their benefits is check employee or plus spouse or family. Even paying can be complicated because they’ve always had their benefits just taken from their check, so even that process is daunting.”

Walton says Alight has a team that analyzes local plans and looks at prices, benefits and product ratings to determine if the carriers should be offered on their platform. When the retiree comes to Alight for assistance in choosing a plan, the company performs a needs assessment for that person and their spouse. The beneficiary’s information is placed in the system, and the plan recommendation tool offers up the top-five best choices for that person. The retiree can opt for one of those or look through other options.

Employers have the option not to put money toward a retiree’s plan, but a majority of businesses do contribute through a health reimbursement account (HRA), Walton says. This is often because Alight is able to show employers cost savings when moving a retiree from the group plan to an exchange plan with an HRA contribution.

Walton does this by calculating the cost of removing someone from the group option, assessing the cost of the exchange plan, and determining what Alight thinks the company should reinvest in an HRA. The net savings, including a defined contribution, is typically 20% to 50% of the employer’s spending for that beneficiary. Some employers Alight works with move just a portion of their population to the exchange. Others offer the option to all eligible beneficiaries.

Some employers come to Alight seeking solutions, but Walton also reaches out to businesses in struggling markets to offer the company’s solution. When the

oil and gas market took a financial hit after the pandemic, Alight talked to employers about how to reinvest with an exchange to offer a better solution to retirees in that industry.

When Walton joined the company in 2010, Alight counted 17 employees, who helped transition just over 20,000 retirees. This year, the company will assist more than 700,000 retirees, about 98% of whom will stay on the plans they originally chose year over year.

Alight works with clients over time so beneficiaries continue to have the best option. Employers are also kept in the loop. Alight provides the companies with information that includes how many retirees were contacted and enrolled and the distribution of people who chose Medicare Advantage or a supplemental plan.

“Financial pressure is the catalyst for employers working with us; then, they see our solution,” Walton says. “This allows the employer to continue the promise they made before to offer health benefits; they are just doing so in a different way. Employers are under cost pressures, and when they make a decision to change, we provide them with a service that offers retirees a soft landing.”

Interpreting Alphabet Soup

Most companies don’t offer any benefits assistance to people either retiring or staying on at age 65. If an employer wants to be out of the insurance business for retirees, it can be. For those staying on, they can simply ask if they want the group plan or Medicare. But if companies want to provide something to their employees to help with the transition, education is always an option.

“Medicare is kind of like a foreign language,”

says Bigham, of Boomer Benefits. “You are used to what you’ve had with an employer. Then, when you go on Medicare, you have supplements, with an alphabet of letters to choose from, or advantage with an HMO or PPO.”

Her organization works with businesses of all sizes to educate both benefits staff and employees. For staff, she may create a 101 on Medicare to better understand the product and help employees with their decision-making.

For employees, she may work with a business offering a webinar for anyone 62 and older, which she says is the time to start thinking about Medicare. Employers can market to that group and show it every year or two, depending on how many people are in that age bracket.

Any kind of resource employers can provide is helpful, she says. Businesses can steer employees to websites or direct people to YouTube videos explaining Medicare (of which there are a plethora). Bigham says most people she deals with are very uninformed about retiree health benefit options. Some people think Medicare is free. Others think they aren’t eligible if they are still working at 65.

For instance, a person who works for an employer with 20 or more people probably has coverage that counts as “creditable.” This means the person can stay on his employer’s plan and not receive penalties for enrolling in Medicare after age 65. But smaller employers’ plans may have higher premiums, so a beneficiary could save money in both premiums and deductibles by moving to Medicare. Also, some small employers’ drug plans might not be creditable or nearly as robust as a Medicare Part D plan.

Bigham says she even works with financial planners who don’t understand the system to help their clients determine their best options at 65.

For instance, if someone is going to turn 65 in a few years, she would talk with them about what they like best about their current insurance, their current out-of-pocket costs, the benefits they most use, and the medicines they take. That information can be used to determine what kind of plan might be the best fit or if they should stay with their employer’s plan if they are continuing to work.

“Health is also a big component,” she says. “Just because someone is healthy now, they may not be as they age. People have to think about what they can afford in the future, what their finances will be like and what their out-of-pocket costs could be if they have a health issue. It’s good to get ahead of it when you can, and providing any resource, education or information is an inexpensive benefit to offer.”