Skills Gap

Looking at today’s unemployment numbers in many parts of the world, it’s difficult to imagine a time when there will be a labor shortage.

But that’s exactly where we are heading in the very near future, according to McKinsey global institutes, the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Co.

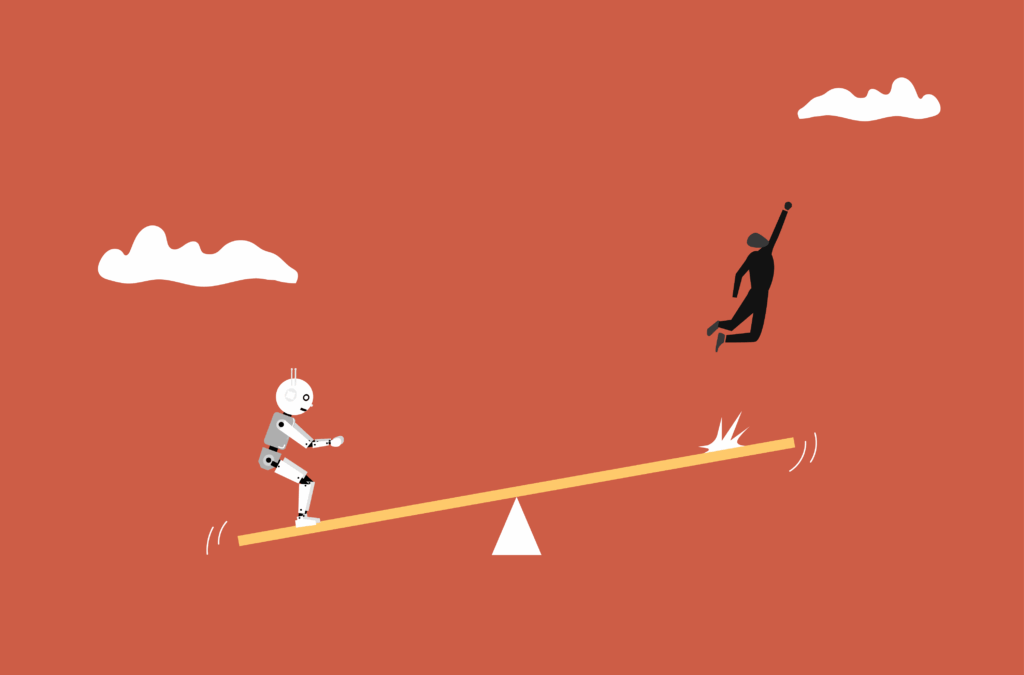

What a labor shortage means for our industry is that talent will be even harder to attract. Technology, financial services and other new industry businesses will be snatching up college-educated, highly skilled workers faster than they can be graduated. What it means to society at large is a growing gap between the haves and have-nots.

Strains in our labor market have been developing for years, but a booming global economy over the last three decades created millions of new non-farm jobs in developing countries and lifted millions out of poverty. Even as the world’s economy slowly recovers and new jobs are created, unemployment remains high. While many people around the world are prospering and improving their economic lot in life, many are not.

How can you have a labor shortage and high unemployment? McKinsey identifies the problem as a “skill” gap and one that is widening in developed, as well as developing, nations. “Even as less-skilled workers struggle with unemployment and stagnating wages, employers face growing shortages of the types of high-skill workers who are needed to raise productivity and drive GDP growth.”

McKinsey explores this issue in its report, “The world at work: Jobs, pay and skills for 3.5 billion people.” The factors driving the imbalance between labor supply and demand will grow stronger. The result will be “too few workers with the advanced skills needed to drive a high-productivity economy and far too few job opportunities for low-skill workers.”

The report highlights some of the most significant factors driving the imbalance. By 2020, employers could face a shortage of 40 million highly skilled workers, or 13% of what they need. Breaking that down, employers in advanced economies could face a shortage of 16 million to 18 million more college-educated workers. The remaining gap will be found in China, which will need another 23 million highly skilled workers to keep its growth on track.

On the flip side, as many as 95 million low-skill workers around the world will be without jobs, which is 10% of all low-skill workers. Developed economies may have a surplus of up to 35 million low-skill workers. India and other young developing countries could have 58 million unemployed low-skill workers.

The report also says developing economies could face a shortfall of nearly 45 million medium-skill workers, or 15% fewer than needed. India and industrializing countries in Southeast Asia and Africa will need far more people with secondary education and vocational training. But high school enrollment remains low in those regions. For India, that adds up to 13 million fewer medium-skill workers than employers will demand. The younger developing countries will need about 31 million more workers by 2020.

If these trends continue, the implications for society, business and the economy are grave, McKinsey notes. Europe, the United States and other advanced countries could face chronic, long-term unemployment. Young people without college degrees and older workers without the skills in demand could be locked out of the labor market. Business productivity will slow. Social tensions will build as the income gap widens and living standards decline. And governments will have to provide more social welfare programs.

Without highly educated and skilled workers, China will not be able to sustain its growth into “value-added industries.” Millions of Chinese will be “trapped in subsistence agriculture or in urban poverty.” McKinsey sees a similar scenario playing out in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

To head off the worst possibilities, advanced economies would have to double their graduation rates in higher education and increase the number of science, engineering and other technical field graduates. Other strategies include retraining mid-career workers; allowing more highly skilled workers into their countries; encouraging more highly educated women to enter the labor market; and keeping older highly skilled workers. McKinsey estimates that these measures would narrow the gap, leaving “only” 20 million to 23 million workers without the skills employers will want.

Developing nations have an even greater challenge, says McKinsey. One billion workers could lack a secondary education in 2020. And hundreds of millions of those without the relevant job skills will need to be trained. To fill the gap, high schools and vocational training schools “would have to grow at two to three times the current rates.” In addition, the economies would have to “double or triple labor-intensive exports and investment in infrastructure and housing construction to employ low-skill workers.”

For policymakers, business leaders, and workers, McKinsey says, the way forward will require improved education and training systems “to build pipelines of workers with the right skills for the 21st-century global economy.”