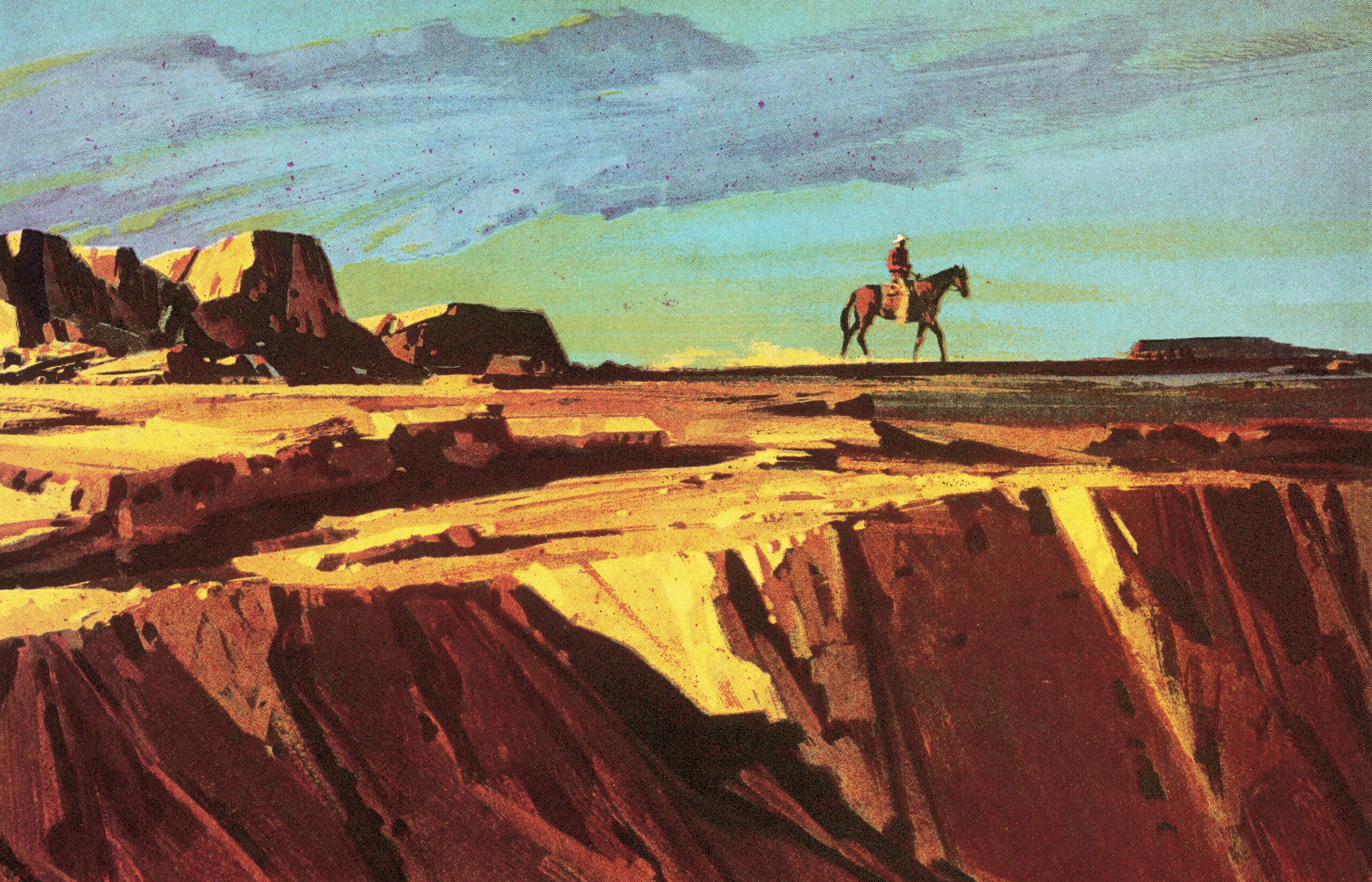

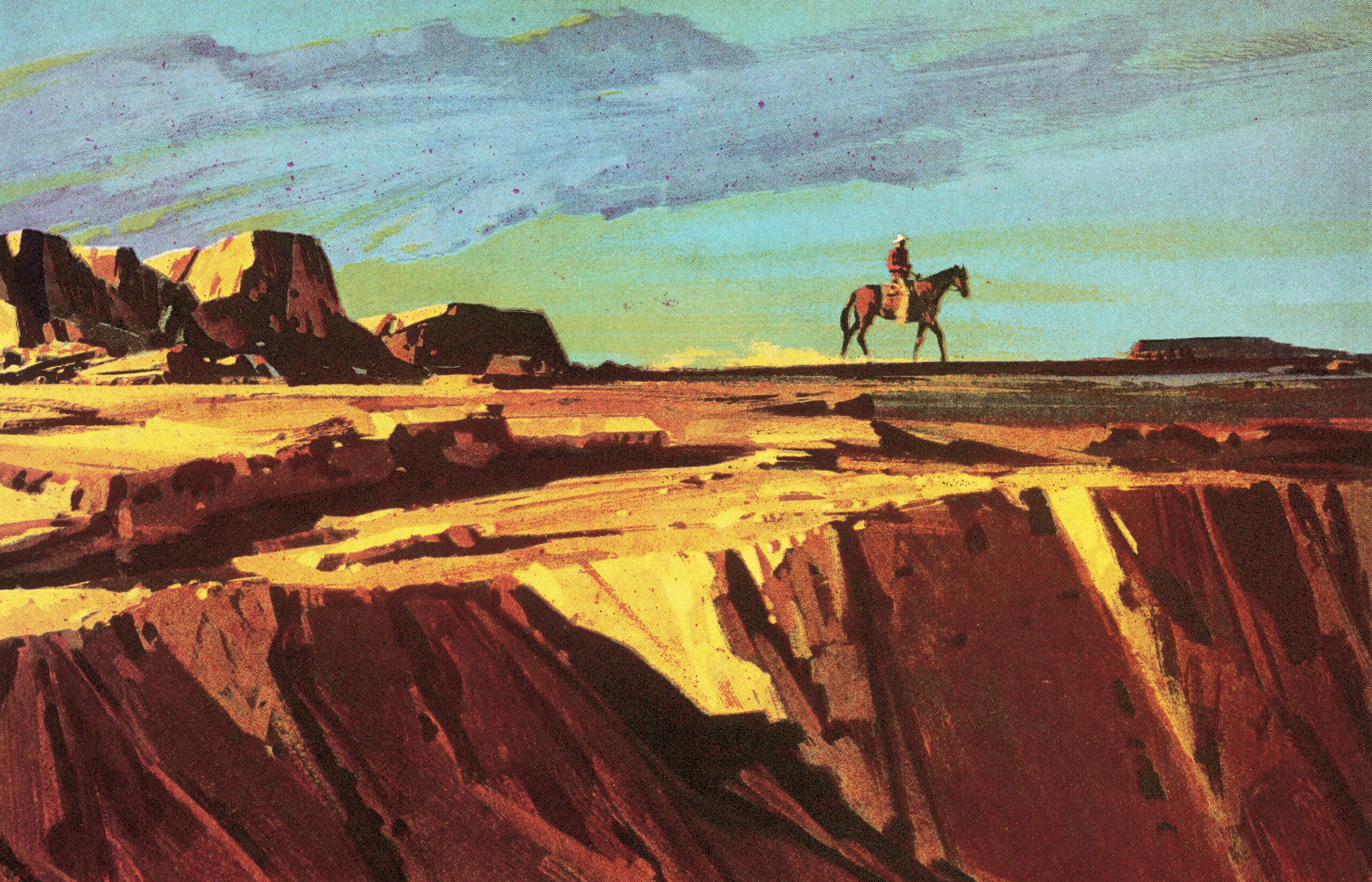

Soldiers engaging in combat with native tribes in post-Civil War America.

The free press waging a war of words on companies in the Wild West. A massive parade celebrating the tricentennial of the Massachusetts colony. These are all scenes that shaped the way American’s think about risk, from author Katherine Hempstead’s new book Uncovered: The Story of Insurance in America. The book shares how the American insurance industry developed over a period of centuries.

In this discussion, Hempstead takes us through the stories and people in her book.

Read the Transcript

Disclaimer: Podcast transcriptions are computer generated, please excuse errors. For the most accurate version of the conversation, please refer to audio.

Katherine Hempstead:

This life and death that seems so remote from our present-day life. Being in a battle with Native people and dying in this remote location, it seems very distant from our present-day experience. Life insurance, especially in the 19th century, when life insurance was an innovation and some people disapproved of it because they thought it would prevent people from saving or it was a little bit speculative. It was an innovation and had to be sold.

Zach Ewell:

Welcome to the Leader’s Edge podcast. I’m Zach Ewell, content producer here at Leader’s Edge. Soldiers engaging in combat with Native tribes in post-Civil War America. The free press waging a war of words on companies in the Wild West. A massive parade celebrating the tricentennial of the colony of Massachusetts. These are all scenes from author Katherine Hempstead’s new book, Uncovered: The Story of Insurance in America. The book shares how our insurance industry came to be, through the lens of American history. Sprinkled through her book are stories about real people and historical moments that transformed how we have come to know risk. Give this conversation with the author a listen.

Katherine, you start the first chapter of your book off with a bang. Named “The Birth of a Business,” the chapter opens in post-Civil War America with a man named Lieutenant Frederick Henry Beecher engaging in combat with native tribes on the border of Kansas and Colorado in 1867. You share that hundreds of warriors, armed with rifles, lances, and arrows engaged in this battle that left many casualties, including that of Lt. Beecher, who apparently dragged himself over to a nearby town before dying. Some of his last words were, “I have my death wound, General. I am shot in the side and dying.” That’s quite a way to start your book, which is about the history of insurance in America. What is the tie-in with this real gruesome event and how insurance in America was birthed?

Katherine Hempstead:

Thanks for asking. That’s a great setup for me. I think the contrast that I wanted to draw was how this life and death that seems so remote from our present-day life. Being in a battle with Native people and dying in this remote location, it seems very distant from our present-day experience. The tie-in is that when the unfortunate lieutenant’s family tried to collect on a life insurance policy he had purchased, their claim was denied on a technicality because he had not paid a surcharge for a war risk charge that had been deemed due by the insurance company. It turned into a huge brouhaha that involved the insurance press, different friends and family members of Lt. Beecher, and the insurance company in question. In some ways, it reflected the state of insurance regulation at the time, which was relatively loosely regulated. A lot of issues were worked out in an ad hoc way that involved the press.

In another sense, it seemed like something that could happen today and really resonates with experiences a lot of people have where they have a claim denied by an insurance company, whether it’s correct or not. They don’t understand it. It seems arbitrary or capricious. They get angry, they complain, and many times, still, people use the press to prosecute charges against insurance companies, whether rightly or wrongly. I see that all the time in my job at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, where I work on health insurance. I see those stories come up very frequently and create a lot of discussion.

It really goes to the heart of the book, which tries to focus on what is public and what is private about insurance. How do we figure out, as a society, what is fair and how should certain issues be decided upon? When insurance issues get dragged into the public square and when people feel that insurance companies are making arbitrary decisions that are not in their favor, there’s a real through line from the past to the present.

Zach Ewell:

That’s so fascinating. I feel like you can make a whole Western movie about that. The first act is the battle, and then the second act is trying to get the payout.

Katherine Hempstead:

Some people might walk out in the middle, but I think I would sit to watch the whole thing because it was a great story.

Zach Ewell:

Maybe it’s like a courtroom drama or something like that at the end, or like you said, playing out in the press. That’s very fascinating. I want to ask about the cover of your book. It looks as though there are people dressed up as pilgrims and they’re protesting or participating in a parade. Which is it?

Katherine Hempstead:

It’s a parade. I have to thank the Insurance Library for sharing this picture with me and letting me use it in my book. The title of the picture is called Parade of Insurers, and the occasion is a large parade in Boston to celebrate the tricentennial of the colony of Massachusetts. It’s in the 1930s. You can see a lot of umbrellas out, it’s a rainy day. I suppose what happened was all the different kinds of businesses in Boston participated in the parade and dressed up as pilgrims. The insurance companies, brokers, and agencies are carrying these signs that all say insurance at the top, which makes me think there are probably other industries. This must have been a very big parade. It says “Insurance,” and then the name of the company under that. It was taken by the Boston Globe, this picture, but I don’t think it was actually in the paper. It wasn’t published as one of the photographs that was used in coverage of the parade. They probably take many more pictures than they use. I thought it was a great cover for this book.

Zach Ewell:

Switching topics now, as I understand it, your book dives into the crucial role that insurance has played in American politics. Can you expand on that for me? Does that have to do with a specific politician?

Katherine Hempstead:

What it really focuses on is the constant tension that we’ve had between what is a business issue and what is a policy issue around insurance. It traces the history of the business itself and its interaction with government. One of the things that’s interesting about insurance in the US is the fact that it’s regulated by the states. The book goes into talking about why that came to be, why that’s significant, and how it’s made it hard to solve certain kinds of problems, especially problems that require public funding, which is usually hard to get at the state level.

In the beginning of the book, the federal government is not very important. The federal government isn’t large, and the federal government isn’t very involved or interested in insurance. Around the time of the Depression and the New Deal, it’s an inflection point where we start to see the federal government emerging as a significant provider of insurance with Social Security and the Agricultural Adjustment Act, unemployment insurance, which is done by states but has federal direction, and then also starts to become more interested in potentially scrutinizing the insurance industry in various ways, so we start to see the different kinds of congressional hearings. I think it’s not so much about politics per se, but it’s about the way the insurance industry has interacted with state and federal government over time.

Zach Ewell:

When it comes to the concept of insurance, America has not been the first nor last country to build up its own industry in this sector. For instance, Lloyd’s of London has played an instrumental part in the world of risk. In your opinion, based off your book, what’s unique about the American insurance industry?

Katherine Hempstead:

One of the things that’s interesting, and I don’t know as much as I wish I did about insurance in other countries, but one of the things that’s an interesting characteristic of insurance in the US is earlier in the 20th century, there was a really big interest on the part of the companies to not have a duality, where insurers from the outset would say that what they were doing was something that transcended mere commerce. It was a social enterprise, which certainly is not untrue, but that didn’t go along with wanting to have any partnership with government or have any government involvement in insurance. The insurance industry was very grudging about any public participation in insurance and were very wary about what they saw as overstep by the government.

At the same time as that was going on, as they successfully kept the US from adopting some of the national social insurance programs that were more common in other countries, the industry became quite rigid itself in some ways, especially the property and casualty industry with the rating bureaus, they very rigidly defined organizational hierarchies and divisions between property insurance and casualty insurance.

One of the ironic things that people noted around the time that the auto really became important, and there’s a chapter on this in the book. Auto created a challenge for the insurance industry because it mixed so many different risks. It does seem silly to think about it now, but at the time, until the mid-20th century, people had 10 different policies to protect against all the different kinds of risk: property liability, damage to the car, damage to something else. It took the American insurance industry a long time to be flexible enough to create comprehensive auto insurance because they had built these very rigid structures. Meanwhile, in England, where there was a much bigger public presence in terms of national health insurance, the private industry was much more flexible. There was a time when a lot of auto business was going to Lloyd’s and going to British companies because the US insurance industry had become so governmental and so bureaucratic that it had a lot of trouble getting itself together.

Zach Ewell:

In your research for this book, you said that property insurance is a hot topic, specifically how the coverage is becoming less affordable due to climate change and natural disasters. How did the insurance market in the past overcome these risks?

Katherine Hempstead:

That’s a great question. One of the things the book goes through is different examples of coverage gaps in different lines of business, so different times when there was a real hue and cry about the affordability of insurance and people tried to make it into a policy problem with different outcomes. The first thing you may think of is fire insurance. At the very early days, at least when my book takes off, and fire insurance is older than my book, but late 19th century, a big problem with fire insurance wasn’t affordability but insolvencies. People didn’t know how to price the risk. They would compete just to get business. Agents had mixed incentives and would take all kinds of bad risks. When there would be a fire, it’d be a conflagration in the city. A lot of things would burn down, a lot of companies would go out of business, so that was a big problem for consumers, not really an affordability problem.

Later, that problem got solved through better regulation and underwriters started to figure out some more things about how to price risk and develop the maps and schedule rating and stuff like that, so that problem went away. Then there were episodes where many consumers felt like fire insurance was completely unaffordable. They would make all these improvements in their town and argue that their rates still didn’t go down. They would improve their water supply or meet these building codes . The way that finally got solved was through loss reduction, because there started to be fewer fires. People started to use different building materials, fire departments did get better, more things were fireproof, and there just was less fire, so losses declined. That was when coverage expanded, and we started to have what we think of as a comprehensive homeowner’s policy that included a lot of other things beyond fire.

That was one example where there was a coverage gap. Another good example is auto. When auto started to take off and comprehensive auto policy started to be written in the mid-20th century, there were a lot of accidents, lots of costly litigation, because for a period of time, roads weren’t safe, there weren’t DUI laws, cars weren’t as safe. There was so much growth in volume and growth in miles traveled and not the safety infrastructure to keep accidents down. There were many accidents, and premiums were going up a lot. We started to see auto insurers doing the things that we’re talking about today with the property insurance problem that we’re having, where they would not want to sell policies to people, maybe, who are older, or because juries were so important in litigation, they wouldn’t want to sell policies to people that they didn’t think would present well in front of a jury. There were a lot of things that seemed unacceptable to consumers.

Given that insurance was mandatory for driving, it became a really serious problem. There were congressional hearings and talks about it. What really happened, to be honest, was that cars got safer and driving improved and traffic enforcement improved, highways were built, and losses came down. Not to say that there aren’t still problems with the affordability of auto insurance, and I know in recent years, accidents have gone up again, there’s a lot of reckless driving and impaired driving. That was a problem that this new technology, the auto, disseminated quickly before there was an infrastructure around it, and there were a lot of losses. The insurance industry reacted to it by trying to avoid risks that they didn’t want to take. Then that became a big social problem and a big policy problem. It put certain kinds of drivers at a big disadvantage, and it was a crisis for a while, like a hard market. It’s gotten better, but it’s really because losses went down and that made things more manageable.

Zach Ewell:

Does your book at all touch upon the history and transformation of insurance brokers throughout American history at all?

Katherine Hempstead:

It talks about agents to a certain extent. I wished I had included more on how that changed over time. The fire insurance agents had a lot of independence. They worked for more than one company often, and they could make a lot of decisions on their own. A lot of times, insurers would be very angry at them for taking bad risks or for thinking that they had allowed people to overvalue their property. There are these interesting conflicts between buyer agents and insurance companies. Life insurance, much more, adopted a perspective of having these branch offices and having agents that work for the company. They had this, some of the big companies, very organized system of promotions and rewards for sales.

A big difference, that I hadn’t thought about until I started working on this, was that at the time, and it’s probably still a little bit true, fire insurance or property insurance didn’t need to be “sold” as much because everyone accepted the need for it and wanted to buy it. It was just a matter of being able to afford it, whereas life insurance, especially in the 19th century, when life insurance was an innovation, and some people disapproved of it because they thought it would prevent people from saving or it was a little bit speculative. It was an innovation and had to be sold, so there was a different vibe among life insurance agents that really prioritized their salesmanship because they had to get people to buy coverage that might not otherwise buy it. Fire insurance is a little bit different. What they were trying to do was really assess the risks on the ground. That was one of the interesting ways that agents were covered in the book.

Zach Ewell:

That was my interview with author Katherine Hempstead. I hope you enjoyed it. For more podcasts, go to leadersedge.com.