Data Failures and Lawsuits Are Piling Up

Data breaches cause a democratic kind of pain.

No matter the size of the company, the disruption is often the same: interrupted operations, reputational damage, and lost business.

The top 10 data breach settlements in the United States in 2023 totaled $515.75 million, a nearly 50% increase from $350 million in 2022. In 2024, the top 10 total rose 15% further, to $593.2 million.

In 2023 and 2024, plaintiffs began to leverage older laws like the 1967 California Invasion of Privacy Act and the 1988 federal Video Privacy Protection Act to target businesses with class actions, and courts have been receptive.

Both insurers and brokers have an opportunity to step up to promote cybersecurity and data privacy best practices for insureds to help them navigate this new normal.

Meanwhile, data privacy violations have become increasingly widespread as companies struggle to keep up with the growing number of data protection regulations in the United States and abroad. Here, small or medium-sized businesses suffer more than larger companies that have the resources to employ data privacy consultants to help them through regulatory changes and develop data privacy strategies.

Customers or shareholders affected by breaches, or whose data privacy has been violated, have increasingly added a new source of pain for the business world: class action litigation, with encouragement from the plaintiffs’ bar.

“Class actions tend to be exceptionally lucrative for plaintiffs’ counsel,” says Tara Bodden, general counsel and head of claims at cyber insurance company At-Bay. “We see a clear uptick in plaintiffs’ counsel jumping into this lucrative field and using aggressive social media campaigns to get clients.”

Sources for this article identified two areas where class action litigation is most common when it comes to data: after a company files a data breach notification and as a result of data privacy concerns over the use of website activity tracking methods, such as cookies, email tracking pixels, and session replay. These kinds of litigation are distinct, emphasizes Anne Juntunen, senior claims manager for cyber firm Coalition. While a business is generally victimized by a data breach that could then lead to it being sued, data privacy claims require a level of intentionality on the company’s part. As she puts it, “I gave you my information willingly, and then you knowingly used it in a way that I didn’t expect you to use it.”

The costs for both kinds of litigation are very real. According to multinational law firm Duane Morris, the top 10 data breach settlements in the United States in 2023 totaled $515.75 million—a nearly 50% increase from 2022’s top 10 total of $350 million. That rose by another 15% in 2024 to $593.2 million.

The cost of data privacy litigation is harder to quantify when it comes to average settlement or damage amounts, given the limited number of cases and rulings.

Nevertheless, some landmark cases suggest costs could reach as high as those seen in data breach settlements. For example, in the federal case Rogers v. BNSF Railway Co., a jury initially awarded roughly 45,000 plaintiffs $228 million in damages over the railway’s fingerprint scan mandate for facilities in Illinois. While a judge later vacated the award due to its substantial size, BNSF still paid $75 million to settle the case in 2024, according to Reuters. That amount would make it larger than nine of the top ten settlements on Duane Morris’s list of top 10 data breach settlements in 2024. (The top settlement that year was the behemoth $350 million for Alphabet after a software glitch led to the exposure of Google+ users’ data for three years.) The Rogers plaintiffs’ attorneys will seek up to 35% of the settlement fund, potentially standing to rake in $26.2 million.

The cost of class action litigation over data breaches and data privacy translates to higher cyber claim frequency and severity worldwide, Allianz indicated in an October 2024 report. According to the report, the frequency of large cyber claims worldwide, defined as claims costing over €1 million ($1.1 million), rose 14% in the first half of 2024 on a year-over-year basis, while large cyber claim severity increased by 17%. Two-thirds of those large cyber claims had data breach or data privacy incident litigation elements.

The United States accounted for 72% of those large cyber claims in that six-month period of 2024, rising from 41% in 2023. Not only that, 100% of the reported large cyber claims in the United States in the first six months of 2024 involved data privacy incident litigation. Michael Daum, global head of cyber claims for Allianz Commercial, sums up the situation in the report, saying that data privacy incidents can “generate losses of a magnitude we are not used to in the cyber insurance market. We are now seeing claims for ‘non-attack’ data breaches [data privacy incidents] in the hundreds of millions of dollars, while the total cost will be even higher as reputational damage is not insured.”

So far, it seems that these claim losses have not materially impacted cyber insurance rates. The Council of Insurance Agents & Brokers’ P/C Market Survey shows that premiums for cyber insurance declined during the last three quarters of 2024.

Additionally, in S&P Global’s Cyber Insurance Market Outlook 2025, released November 2024, the financial information and analytics firm said that the previous rate spike during 2020 and 2021, as well as the stricter risk controls imposed by insurers, are contributing to the market’s continuing stability.

According to Bodden, however, “While rates are stabilizing, cyber losses have been on the rise.” S&P Global also warned that “given the dynamic threat landscape, a combination of stagnant or even declining cyber rates and a sharp increase in underlying cyber claims could quickly result in a material decline in profitability.”

Still, Juntunen cautions that because cyber policies cover a mixture of first and third-party losses, it can be difficult to ascribe a change in pricing to one particular risk, even if data breach- and data privacy-related claims are increasing. Nevertheless, she says Coalition is “closely watching the data to ensure pricing remains both sustainable and responsive.”

Data Breach Transparency Lures Lawyers

Cyberattacks, which can lead to a data breach, continue to ramp up. NCC Group data shows that the number of ransomware attacks globally rose 15% from 2023 to 2024, from 4,667 to 5,263 incidents—and the 2023 numbers were already up 84% from 2022. North America accounted for 55% of the 2024 attacks, a total of 2,869, 23% more than the 2,330 recorded in 2023.

Analysis of legal complaints suggest those attacks are translating to more litigation in the United States. A Bloomberg Law study found that the number of federal complaints mentioning both “data breach” and “ransomware” rose from 104 in 2021 to 736 in 2023—a 608% increase, Juntunen notes. “We’re certainly seeing an increase in the number of cyberattacks involving large numbers of affected individuals and high-profile companies,” she says. “That’s just brought more attention to the issue, and that makes those cases riper for plaintiffs’ firms that are specialized in this area to assemble a class.”

Data from Duane Morris shows a total of 1,488 class actions were filed over data breaches in 2024, up from 1,320 in 2023 and 604 in 2022. In 2018, there were only 108 data breach class action filings— meaning the number of these cases rose by nearly 1,300% in just six years.

That is partly due to data breach notification laws, according to Bodden and Juntunen. “Most states require that companies who suffer a breach notify them,” says Bodden. “This means that once your company does the right thing and complies with that law, the information is publicly available and searchable— which is how many plaintiffs’ counsels target their next class action.” Thirty-five U.S. states require that a company notify the state government of a data breach, according to national law firm Davis Wright Tremaine. Almost 20 states, including those with robust data protection laws like California, have public websites that list data breach notifications received by the state attorney general.

Websites such as classaction.org and topclassactions.com also collect data breach notifications—and since all 50 states at minimum require that companies notify individuals affected by a data breach, these sites can cast a wide net for possible lawsuits. Top Class Actions has its own section for data breach lawsuits a prospective plaintiff could join and enables attorneys to seek specific kinds of class action plaintiffs.

“Got a data breach notice?” asks classaction.org, which has been active for nearly a decade. “Scroll down to see the list of data breaches attorneys working with ClassAction.org are currently investigating. If you see one that looks familiar, click through to learn more about the breach and what you can do to potentially help get a class action lawsuit started.”

Businesses find themselves between a rock and hard place here. There’s no question that companies should inform affected customers about data breaches to be “good citizens,” as Juntunen describes it. But when doing so invites litigation, and thus even more costs, at a time when the business is likely working to get up and running again, it becomes much more difficult to balance customer and legal obligations with minimizing liability, she says.

For example, consider what Lockton is facing after notifying its customers of a data breach in November 2024 on a single computer. As of April 2025, there are eight federal lawsuits seeking class action status against the broker for allegedly failing to follow industry standards, Federal Trade Commission guidelines, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, reports Business Insurance.

The Fight Over Data Privacy

According to the UC Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, 1,800 federal class actions were filed over data privacy issues in 2023, a roughly 30% increase from 2022.

Most of this litigation stems from two laws: the 2018 California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the 2008 Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) in Illinois.

The CCPA permits individuals to sue companies if their personal information is stolen, exfiltrated, or accessed, or disclosed without authorization. Data privacy cases under this law hinge on the argument that unauthorized access includes data disclosed to third parties (like data analytics firms) by businesses through tools such as cookies or other website activity tracking software.

BIPA protects only biometric information (such as fingerprints or retinal scans). Most relevant to data privacy, it bars companies from collecting or disclosing this data without consent and gives individuals the right to sue companies that breach this rule.

In addition, two new legal theories gained more momentum in 2023 and 2024 for use in class actions. These theories, as Juntunen explains, rely on older laws: the 1988 federal Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA) and the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA) from 1967.

Plaintiff arguments under CIPA rely on the claim that a third-party analytics company that collects and analyzes user activity data for a business’s website qualifies as a true third party. Thus, if the analytics company fails to obtain express user consent for collection and analysis of their data, the third party is allegedly engaged in “wiretapping,” and both it and the business that employs it would be liable for violating CIPA.

“When companies are using any kind of third-party vendor for analytics, they have to be aware of the risk that that third party could be viewed as a true third party to the interactions between the user and the company, and that could be viewed as wiretapping,” Juntunen warns. VPPA cases, meanwhile, turn on the assertion that protected video materials include content such as prerecorded web videos. As such, any company that discloses what videos a customer watches or even clicks on to a third party, in combination with information that could identify that user, without the user’s express consent, would be violating the federal law.

The plaintiffs’ bar seems to be taking these theories seriously. Also per the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, 120 data privacy lawsuits based on allegations of wiretapping liability, mostly under CIPA, were filed in 2023 alone.

“This risk is a difficult thing for companies to minimize because the plaintiffs’ theories on how to pursue these matters are changing so quickly,” Juntunen says. “[The VPPA] was enacted in the age of Blockbuster, but plaintiffs’ attorneys are now recycling that and using it as a theory for grounding privacy claims, and that’s a really hard thing to plan for if you’re not keeping up to date with your privacy policies and if you don’t have a privacy counsel who can help advise you on obtaining very clear consent from the users on your website.”

The nearly 60-year-old California Invasion of Privacy Act was initially passed to prevent wiretapping on phone calls. The law prohibits the use of “any machine, instrument, or contrivance” to tap into any communication via “any telegraph or telephone wire, line, cable, or instrument” without the consent of “all parties to the communication.” It further bars the use of any “electronic amplifying or recording device” to eavesdrop on a confidential communication conducted by means of “telegraph, telephone, or other device,” without the consent of all parties to that confidential communication.

For context, the 2018 CCPA grants a private right of action (the authority to file civil lawsuits claiming harm by a separate entity) only if a consumer’s “encrypted and nonredacted personal information” or “email address in combination with a password or security question and answer that would permit access to the account” are “subject to an unauthorized access and exfiltration, theft, or disclosure as a result of the business’ violation of the duty to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices.”

In comparison, CIPA grants private right of action merely if a plaintiff is “injured by a violation” of any of the privacy rights conferred by that statute—a much lower bar to clear given plaintiffs are not required to show defendants’ dereliction of privacy duties and are not restricted to the specific kinds of personal information laid out in the CCPA.

The damages can also be significantly higher under CIPA, making it particularly attractive for lawyers. The California Consumer Privacy Act allows plaintiffs to sue for the greater of either $750 per consumer per violation or the actual damages incurred by the consumer. On the other hand, CIPA damages are either $5,000 per violation or triple the damages incurred by the plaintiff, whichever is greater.

CIPA’s private right of action was recently legitimized by a case brought in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, Dino Moody v. C2 Educational Systems Inc. et. al. The lawsuit says the defendant partnered with TikTok to install specific software on its website; the TikTok software uses a method to identify visitors known as “fingerprinting,” in which it compares “device and browser information [and] geographic information” collected from visitors to information in the TikTok database. Additionally, because the defendant enabled TikTok’s “AutoAdvanced Matching” feature, the software also captured form data entered on the website, like date of birth, address, and name, according to the complaint.

The plaintiff alleges his information was collected “without express or implied consent” by the TikTok software when he visited the company website on Feb. 28, 2024. In July 2024, the court denied the defendant’s motion to dismiss because (among other arguments) criminal statutes, like CIPA, generally impose solely criminal penalties and thus do not create a private right of action. U.S. District Judge R. Gary Klauser acknowledged that the defendant was correct that criminal statutes don’t typically enable private lawsuits—but noted that the plain text of CIPA’s Section 637.2 “expressly states” that all violations “confer a private right of action.”

As CIPA’s text expressly states, anyone who employs someone who records or taps into these communications, or who uses information gained through this “wiretapping,” could be liable for penalties of $5,000 per violation.

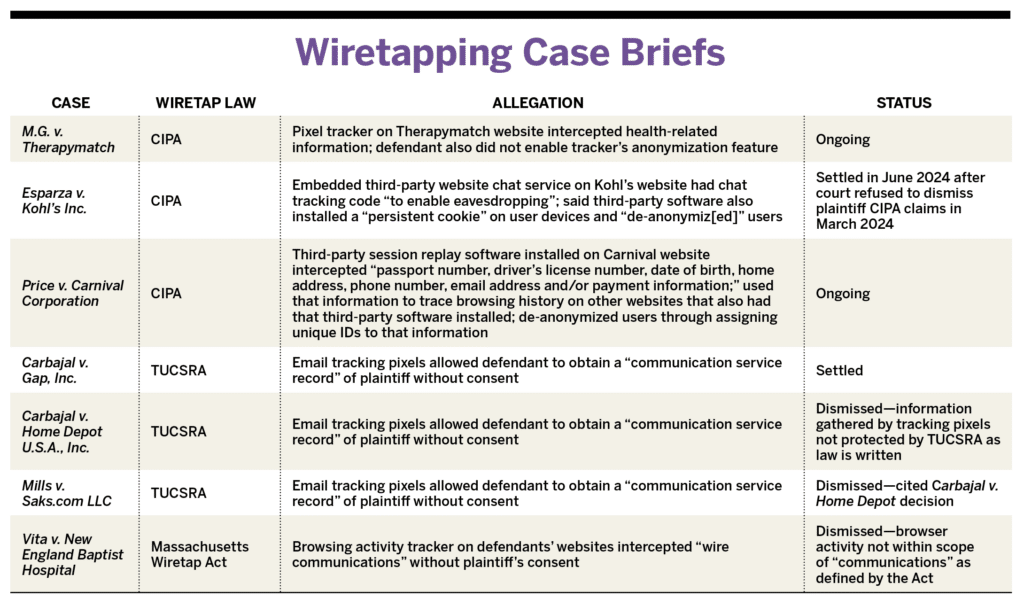

Besides CIPA, the Massachusetts Wiretap Act of 1968 and the Arizona Telephone, Utility, and Communication Service Records Act of 2007 (TUCSRA) were most often invoked in recent data privacy class action litigation about wiretapping in other states, according to a 2025 report on 2024 data privacy litigation trends by multinational law firm WilmerHale.

Anecdotally, courts seem less receptive to the Massachusetts law and TUCSRA, in contrast to CIPA cases, WilmerHale suggests. For instance: M.G. v. Therapymatch, Esparza v. Kohl’s Inc., and Price v. Carnival Corporation, all brought in part under CIPA, survived motions to dismiss, while Vita v. New England Baptist Hospital—brought under the Massachusetts law—and Carbajal v. Home Depot U.S.A., Inc. and Mills v. Saks. com LLC—both brought under TUCSRA— were dismissed outright. (See Sidebar: Wiretapping Case Briefs) M.G. v. Therapymatch, Esparza v. Kohl’s Inc., and Price v. Carnival Corporation reinforce Juntunen’s point about the need for caution when using third parties for data collection and analytics on company websites. The first two target the use of third-party email tracking pixels, while the third attacks session replay technology, which records a visitor’s activity on a website (such as mouse movement or keystrokes and replays that activity for outside analysis).

Equally concerning for defendants and their insurers, the ruling denying dismissal of Price also affirmed the plaintiff’s interpretation of the word “device”—as in the prohibition by CIPA and other wiretap laws on intercepting communications by means of a “telegraph, telephone, or other device”—to include the tracking technology at issue.

“As Carnival reminded this Court at oral argument, the internet is not magic,” wrote U.S. District Judge Gonzalo Curiel. “Like a recipe without a chef, or sheet music without a musician, software cannot function—much less collect and transmit data at hyper-frequent intervals to a third party—without hardware to run it. Because a computer that executes software is undoubtedly a physical device, the motion to dismiss fails on these grounds as well.”

“Bork Bill” Brings New Battles

After the publication in September 1987 of then-Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork’s (fairly mundane) video tape rental history in the Washington, D.C. City Paper, Congress moved with surprising speed to preclude comparable invasions of privacy from happening again. The Video Privacy Protection Act, which bars “any video tape service provider” from “knowingly disclos[ing]” any information about a “consumer” that “identifies [a consumer] as having requested or obtained specific video materials or services from a video tape service provider,” without that consumer’s consent, was signed into law in November 1988.

Similar to CIPA, the VPPA creates a private right of action for violations, allowing for class action litigation. If a court finds a defendant in violation of the VPPA, it may award damages of at least $2,500, punitive damages, legal costs, and attorneys’ fees, as well as other equitable relief that the court deems appropriate.

Only video tape service providers, defined by the law as “any person, engaged in the business…of rental, sale, or delivery of prerecorded video cassette tapes or similar audio visual materials,” can be found liable for violations of the VPPA. Though it is initially difficult to see how this nearly 40-year-old law could apply to internet data privacy, when considering that many businesses today supply content in the form of prerecorded web videos, the path forward for plaintiffs becomes much clearer.

A “consumer,” as defined by the VPPA, includes someone who subscribes to goods and services from a video tape service provider, which opens the way for individuals who subscribe to a newspaper and view video content on its website to sue under the law.

Website activity tracking technologies often record user video viewing practices and transmit them to third parties for analysis—so businesses that employ those technologies without appropriate user consent could be liable for violations of the VPPA, as it could be argued they are “knowingly disclos[ing]” information to a third party that reveals a specific consumer’s video-watching practices.

Duane Morris numbers show that the number of class actions filed over VPPA issues in 2024 totaled 250, nearly double 2023’s 137.

One of the main issues under dispute in 2024 VPPA litigation is the classification of a company as a video tape service provider. According to the VPPA’s definition of the term, a plaintiff must prove two key elements for a defendant to fit the classification: that the defendant delivers prerecorded video tape content and that the delivery of said content is part of its business.

Two federal cases, Aldana v. GameStop in the Southern District of New York and Collins v. The Toledo Blade in the Northern District of Ohio, suggest the courts may be taking an expansive view of what qualifies as a video tape service provider. Both cases, which survived motions to dismiss, involve the defendants’ alleged use of the Meta (née Facebook) tracking, a piece of code that a business can integrate into its website that tracks several specific actions by website users and then sends that information to Meta for analysis. In Aldana, the defendant is also alleged to have taken advantage of a Meta service that allows the company to upload “customer lists to Facebook that contain subscribers’ email addresses and information about what video games they purchased” so Meta can match customers to their Facebook profiles.

The court’s denial of the motion to dismiss Collins found that because the plaintiffs were also Facebook users, each time they accessed a video on the Toledo Blade website, a cookie was sent to Facebook by the tracking pixel containing not just the URL of the video, but also the plaintiff’s Facebook ID, a unique identifier corresponding to their profile. The court considered this a knowing disclosure of the information protected by the VPPA.

Additionally, the court found that the delivery of prerecorded video content does not need to be a major part of a business for the company to qualify as a video tape service provider. In the judge’s words, while the Toledo Blade is primarily focused on delivering written news articles, “[t]he problem for Defendants is that the plain language of the statute requires only that Defendants are engaged in the business of ‘delivery’ of ‘audio visual materials.’ It does not distinguish ‘peripheral or passive’ delivery.”

The Aldana ruling took this even further. Similar to Collins, because the plaintiffs were Facebook users, despite making their purchases on the GameStop website as guests, the website’s tracking pixel allegedly sent information identifying their Facebook profile as well as what games they bought to Facebook.

Video games often incorporate cut scenes, non-interactive prerecorded video clips that push the narrative forward; since GameStop sells video games that have cut scenes, the court ruled, it qualifies as a video tape service provider.

Courts have taken a narrower view on what information is protected by the VPPA in the context of web-based services. The First, Third, and Ninth Circuits Courts of Appeal have all settled on the “ordinary person” test, which asks if an ordinary person can use the disclosed information to identify a specific person’s video consumption habits. As seen in Collins and Aldana, a Facebook ID, which is directly linked to a specific Facebook profile, provided in connection with purchases or video URLs, would qualify as VPPA-protected information, since an ordinary person could easily use a Facebook profile to identify a specific person.

On the other hand, IP addresses, unique device identifiers, and browser fingerprints (a user’s browser and operating system settings) in combination with video-watching practices have been found not to qualify as VPPA-protected information. From the 2016 decision ruling against the plaintiffs for In Re Nickelodeon Consumer Privacy Litigation: “To an average person, an IP address or a digital code in a cookie file would likely be of little help in trying to identify an actual person.”

BIPA’S 2024 Amendment Clarifies—And Confuses

Signed into law Oct. 3, 2008, the Biometric Information Privacy Act in Illinois regulates the collection of “biometric identifiers,” defined as including “a retina or iris scan, fingerprint, voiceprint, or scan of hand or face geometry.” Private companies may not collect this data without the express informed consent of the employee or customer, nor may they sell or disclose that data without consent, unless that disclosure is required by law (e.g., a warrant).

As originally written, the law allowed plaintiffs to sue for damages equal to the greater of $1,000 per violation or actual damages—and if they can show that violation was intentional or reckless, the potential damages rise to the greater of $5,000 per violation or actual damages.

A handful of cases in recent years appear to have spurred class action lawyer interest in the law. In 2019, Rosenbach v. Six Flags Entertainment Corp. established the standard that a party had cause to sue just by demonstrating that a defendant did not follow the law, no concrete harm necessary. In 2023, Cothron v. White Castle reaffirmed that a private employer could be liable for every single time it scanned, collected, or processed employee biometric data without express informed consent.

According to Bloomberg Law, between 2009 and 2018 plaintiffs filed fewer than five BIPA cases a year on average; since 2019 through 2024, there have been at least 130 annually. In late 2023, Tims v. Black Horse Carriers extended the statute of limitations for a lawsuit from one to five years.

In response to the flurry of litigation—and in direct response to Cothron—the Illinois state legislature passed an amendment to BIPA in August 2024 likely to severely limit damages from the law. Under the amendment, the 45,600 violations alleged in Rogers v. BNSF Railway would be considered a single violation for damages of $5,000.

In November 2024, separate Illinois courts split on whether the amendment applies retroactively or just to cases brought after its passage. A final ruling will likely substantively impact the amount of future class actions, particularly as more companies collect and use biometric data ranging from face or fingerprint scans for Apple ID to face scans for internet virtual try-on tools for sunglasses.

This is especially true given BIPA’s stringent data retention and destruction requirements, experts said in a November 2023 Leader’s Edge article. Not only could issues arise from standard IT practices like regular data backups, but employers could be liable if their third-party vendors do not manage employee biometric data appropriately.

Industry Action Needed

Both At-Bay’s Bodden and Coalition’s Juntunen agree that insurers and brokers have a crucial role to play in helping insureds mitigate their litigation risks.

For Bodden in particular, in this new era of litigation it’s not enough for companies to respond to cyber incidents or defend against lawsuits; the key is preventing the incident altogether. It’s a tall order, especially for small and middle-market businesses, but “we know that reducing the chances of cyber incidents occurring is the only real way to manage cyber risk,” she says.

Bodden suggests concrete ways to reduce data privacy and data breach litigation that brokers and insurers both can advise their clients to undertake. A company should remove tracking technologies it is not using; At-Bay has seen multiple companies that didn’t even realize their websites had active tracking tools, she says.

If companies do use these technologies, she advocates ensuring they feature a pop-up opt-in banner for the tracking technology to log customer consent. For tracking technologies like the Meta pixel, she suggests leveraging third parties that specialize in scrubbing the data shared through it to avoid liability down the line.

Besides enforcing security requirements that companies must put in place to qualify for cyber coverage, brokers and insurers can also approach managing data breach risk, according to Bodden. An insurer should not just check whether a company has a particular security control or solution when assessing its risk profile, she says—it should also assess the quality of those controls or solutions via its claims data.

“For example, Google Workspace customers have up to three times fewer email security incidents than Microsoft Office customers,” Bodden explains. “It’s important that we empower our insureds to become better risks by providing them with the knowledge of what steps they can take to improve their security and keep themselves safe before an incident occurs.”

Juntunen agrees that investing in cybersecurity defenses and protections is paramount. Insurers and brokers can help insureds with risk management strategies such as tabletop exercises, post-breach response plans, or litigation strategies. A data privacy counsel is also essential, in Juntunen’s opinion, given how often a data breach notification is followed by lawsuits—that’s why Coalition includes coverage for that role under its cyber policy, she says.

“It’s really important for companies that we get a privacy lawyer in place right away to help them deal with the question of what they are obligated to do and then what might they want to do as a company that wants to have good relationships with their customers,” Juntunen says. “Companies are constantly trying to figure out how to protect their customers and their users without giving them fodder for plaintiffs’ counsel, especially when there’s not much of a risk as a result of a particular data breach.”

This kind of in-depth risk management is complex, but Bodden and Juntunen believe the insurance industry is best situated to handle it. From insurers tapping into claims data to help companies take a more proactive, aggressive stance on cyber risk, to brokers using their unique market and risk management knowledge to guide insureds to the insurer with robust cyber risk solutions, the industry has an opportunity, says Bodden, “to really lean into its role as a mitigator of risk.”