Understanding America’s Spirit Animal

The history of the United States and its people are inextricably intertwined with the survival of the bald eagle.

Both have been shot at, have suffered through pesticides and toxins, have been claimed by various groups in religious rites, have been carried off into war, have struggled against attempts to domesticate, and have had feathers plucked. The fact that the bald eagle survived into the early 21st century is an enduring testament to its adaptability and innate grit.

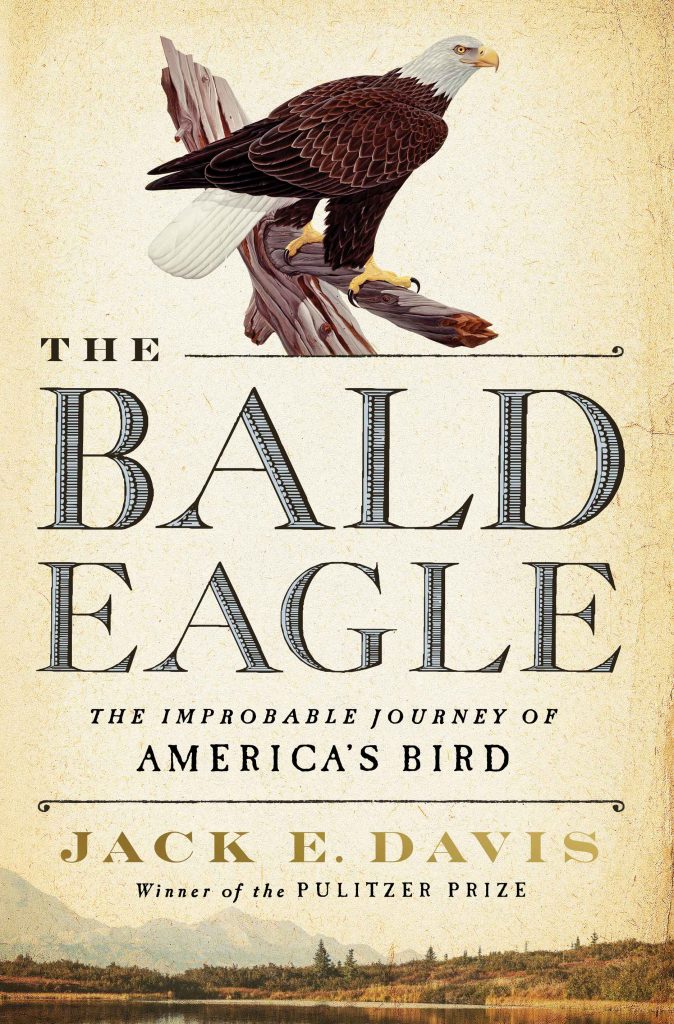

The Bald Eagle: The Improbable Journey of America’s Bird

By Jack E. Davis

Liveright/An Imprint of W.W. Norton & Company

$29.95

In The Bald Eagle: The Improbable Journey of America’s Bird, Jack Davis offers a compelling and vibrant history of the eagle, native to North America, from before the arrival of the Spanish in 1560 in northeastern La Florida through to Dolly Parton’s construction of a million-dollar eagle hospital and breeding area at Dollywood in Tennessee.

Davis is also the author of The Gulf: The Making of an America Sea for which he was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in history. He is a professor of history and the Rothman Family Chair in the Humanities at the University of Florida. Davis is a polymath—historian, environmentalist, researcher, and raconteur—placing the reader into the context of several pivotal moments over the last 300 years of co-existing with the bald eagle.

“Seven thousand feathers clad the bald bird Haliaeetus leucocephalus. North America has no other avian species with a white head and tail and the eagle’s dark body coloring,” explains Davis. “What surely caught the eye of the [Founding Fathers] was the bird’s fierce-looking gaze…Add to that the jet-black pupils and luminous yellow irises, with the absorptive eyes surveilling over a lethal raptor’s beak, and you have the ultimate don’t tread on me stare.” With a wingspan of seven feet, it is easy to understand why the bald eagle was selected as an emblematic symbol during our country’s founding. “The American bird was an ideal metaphor for the patriotic fervor of the time and a young nation staring hard into its future viability.”

Admiration of the bald eagle was not unanimous. John James Audubon, in an 1830s letter, referred to the bird as “lousy, thieving, lazy, dishonest, immoral, and craven feathered national representative.” He had no remorse during his many expeditions over shooting and killing many of them. As Davis notes, “Though something of an inconvenient fact, it seems that America’s most exalted ornithologist hated America’s most exalted bird, the bald eagle.”

Around the start of the 20th century, ornithologists began to study the bald eagle less violently, “reject[ing] guns as the tools of the trade,” and “bearing nothing more than a box camera and shooting pictures,” notes Davis.

In Vermilion, Ohio, near Cleveland, a bald eagle nesting place was gently and professionally studied. Known as the Great Eyrie, it was 12 feet tall and eight and a half feet across the top from edge to edge, offering 50 square feet of living space and weighing two tons. Bald eagles are avian engineers, constructing eyries stick and twig over a period of months and years. They are generally monogamous and return each year to the same nesting site and mate, tidying up and adding sticks to strengthen their home. One or two eggs may hatch eaglets in a season. Hurricanes and suburban development are the enemies of eyries.

With legalized poaching and the rain of pesticides, largely DDT, fouling the air, water, and soil through the mid 20th century, we did almost everything possible to either intentionally or unintentionally eradicate our national symbol from the skies. The bald eagle population declined from an estimate of 100,000 nesting eagles in 1782 to 487 in 1963.

Doris Mager in Central Florida was having none of this. She wanted to call attention to both the plight and the beauty of the bald eagle and their nesting sites. In 1979 at the age of 53, she climbed 50 feet to the top of a loblolly pine into an eagle’s nest that had been abandoned. For six days and six nights, Mager staged a “nest-in,” with food and supplies hoisted to her via a supply rope.

Mager succeeded in garnering national attention and raising money for the construction of an aviary in Orlando. Davis includes many other personal stories of both bald eagle boosters and eradicators.

Laws have been strengthened within the past few decades. Killing a bald eagle now carries the weight of a significant fine and jail time. In 1990, the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge was created in Colorado. The refuge area includes the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Eagle Repository. The bald eagle population in 2020 was estimated at over 300,000.

Davis extends hope at the conclusion of The Bald Eagle: “If animals form a portrait of our virtues and vices, as many contend, then bald eagles have shown us, in our salutary coexistence with them, that our nature is predisposed to virtue.” What we value tells us much about who we are.