It is a rainy, stormy night. Thunder rumbles while bolts of lightning illuminate the sky.

There are too few of these nights in Pass Christian. It is the snuggest time to read thoughtful and insightful fiction while the rest of the town is shaking under bed sheets, fearful of a direct hit.

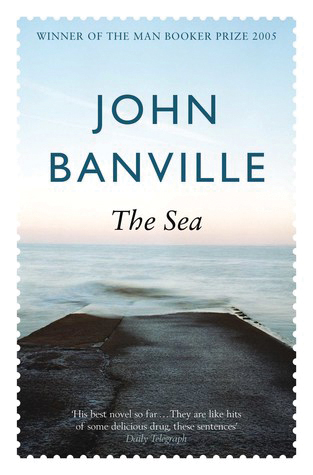

The Sea

By John Banville

Vintage/Penguin Random House

$15.95

It is 9 p.m., and I don’t feel like taking a risk on reading a novel I haven’t read before. Time is precious, and I have three or four hours until I should stop reading and sleep. There is Wallace Stegner’s Crossing to Safety, or Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, or Evan Connell’s Mrs. Bridge, all sure bets. At the other side of the room at the end of a bottom shelf at the end of the alphabet is John Williams’ Stoner, one of the best 20th century American novels. But I walk back across the room to John Banville’s The Sea. It seems perfect for this evening to read of a man’s interior turmoil as the heavens outside unleash barrels of rainwater and treetops whip in response to unpredictable forces.

I’m settled into a comfortable chair in my second-story sunroom overlooking the Gulf of Mexico. BOOM BOOM BOOM, thunders the cannonade in the sky.

The Sea is radiant and intelligent on so many levels.

First, the words: “A steep-slanted flash of sunlight fell along the beach, turning the sand above the waterline bone white, and a white seabird, dazzling against the wall of cloud, flew up on sickle wings and turned with a soundless snap and plunged itself, a shutting chevron, into the sea’s unruly back.” The soft sounds of the “s” appear rhythmically as if set in motion on a trampoline reaching an alliterative apex at “shutting chevron.” The “w” has its way too, bobbing to

the surface while the “s” pauses, “waterline bone white and a white seabird.”

A sentence as vibrant and nuanced as this is not the product of haste. It cannot be franchised. It alone signals a depth of understanding far beyond the common.

There is more: the bonus of a fresh expression, “sickle wings.” I look skyward to visualize the clear, crisp image of the taut, blade-like wings of a purposeful bird turning with a “soundless snap.”

Words must do more than stroll; they must dance. The dance must be choreographed to present an image, to ground the story in a harmonious context upon which the narrative pirouettes.

The physical structure of this novel mirrors life. The Sea has a Part I and Part II. There are no neat chapters arcing within a few pages to conclude cleanly for a manufactured pause before the next unnaturally hygienic chapter. Real life is rarely contained within such artificial borders. We all tend to slop around a good bit with overlap and lagniappe spilling all over ourselves.

The story is unremarkable. Max Morden loses his spouse to cancer after a long and satisfying marriage. His daughter tries to console him. The widower returns to the place of his childhood summer “holidays” to allow the loss to seep into the present.

I recall a quote a few years ago in The New York Times. Best-selling author Christopher Moore commented, “People, even really stupid people, are very complex. If you try to make a character as complex as a real person, then that’s all your book will be about. They call that literary fiction. Hardly anything gets blowed up in literary fiction, so I don’t write it.” Not a thing is “blowed up” in The Sea. The complexity of the main character is the soul of this literary journey. This is a nuanced novel of the wistfulness and vagaries of memory, of the interplay of light and shadow, the “white seabird” darting behind a black, passing cloud.

The entrance that Banville creates for me into Max Morden is embarrassingly intimate. Morden remembers his grieving: “I was there and not there, myself and revenant, immured in the moment and yet somehow hovering on the point of departure.” Continuing in the present tense, “Perhaps all of life is no more than a long preparation for the leaving of it.”

To pique curiosity, I assume, Banville led me into a part of the story through a tilt-shift lens. Familiarity is boring. Recalling a playful day with childhood friends on the beach, Morden remembers the scene now through the filter of time, “But who is it that lingers there on the strand in the half-light, by the sea that seems to arch its back as a beast as the night fast advances from the fogged horizon?”

No child thinks like this. But an adult, sullied and battered by the riprap currents of life, may look back, projecting his or her life rearward, and envision a dread that only a life lived long could instill.

Banville nudges me to an ephemeral silence just beyond the edge of hearing. The tactile page is gone, and I’m beside Morden as his memories bob to the surface and resubmerge into the depths.

There is a silent snap of luminous light, a bolt, a wordless wake of wild white luminescence in the sky. The glass walls of my sunroom intensify the blaze of brilliance like a mirror. For a flash, as I read the final words of The Sea, there was clarity, for a moment, in the lightlessness of the midnight sky.