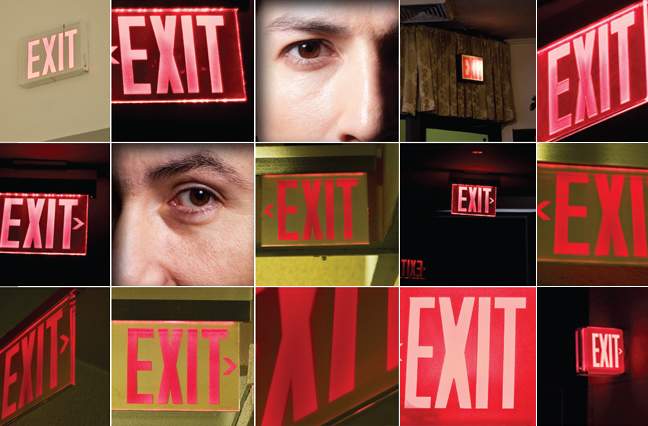

Exit Strategy

If you take a stroll through Maryland’s regulatory revolving door with the state’s new insurance commissioner, Al Redmer Jr., you get a better picture of what’s going on between the regulated and the regulator.

Redmer started out in business, eventually building up his own insurance company and financial services firm, Redmer Insurance Group and Redmer Financial Group, respectively.

Let’s take a half-turn through the door. He eventually entered politics and joined the Maryland House of Delegates in 1991. He developed an expertise in health and healthcare issues, including health insurance, and served on various related legislative committees. He eventually became the chamber’s minority leader in 2001. Like most state legislatures, Maryland’s is part-time, so Redmer stayed in the insurance business. Now take a full turn.

In 2003, Governor Bob Ehrlich—the first Republican to be elected governor in heavily Democratic Maryland in more than three decades—picked Redmer as the state’s insurance commissioner. When he became a full-time regulator, Redmer sold his business to avoid a conflict of interest.

Now take another spin.

Redmer was offered the CEO job at Coventry Health Care of Delaware in 2005 and left the commission. When Democrats returned to power in 2007, Redmer became partner and president of Landmark Insurance & Financial Group in Baltimore. He also started his second insurance company.

One last trip, at least for now. Republican Larry Hogan stunned Democrats when he won the governor’s mansion last year. In Maryland, Republicans have held statewide offices so seldom there is not always a lot of GOP expertise for a governor to build a cabinet around. Given Redmer’s solid reputation and his role as an advisor to Hogan during the campaign and transition, it was not a surprise when the new governor appointed Redmer as insurance commissioner.

One of Redmer’s first orders of business? Sell Redmer Insurance Group. “For the last time, I might add,” Redmer joked.

Do all these swings in and out of politics and the insurance industry raise even a hint of a conflict of interest that could perhaps make Redmer more accommodating toward the industry? Redmer, who says he prides himself on being a zealous guardian of insurance consumers, points to those who would have likely circled like sharks if they saw a weakness—the senators who held confirmation hearings on him in February. “In a heavily Democratic Senate, my ties to the industry never came up,” he says. “No one mentioned them, even once.”

But not all appear to be so scrupulous about appearances. Arkansas Commissioner Julie Benafield made decisions favorable toward United Healthcare in 2007 and 2008. She resigned her post in late 2008 to work for United

Healthcare as its regulatory affairs director in Arkansas and Tennessee, a case that the State Integrity Investigation project said prompted Arkansas to pass legislation barring regulators from immediately working for companies they regulate.

Benafield, who was named the chief deputy attorney general of Arkansas in January, did not respond to a request for comment. But in the past she has repeatedly denied doing anything improper as commissioner.

“No matter how I ruled on anything…somebody would have said, ‘She’s ruling that way so she can get a job,’ ” Benafield told Arkansas Business in 2009. “There’s no way I could win for losing.”

Benafield also said it was her expertise and contacts with other state commissioners and staff that made her a valuable commodity in the private sector.

Conflict or Experience?

A 1979 study by what was then called the General Accounting Office found roughly half of state insurance commissioners came from or returned to the industry. Various studies since then have found little change in that number over the years. That consistent coziness has long led to complaints by government and consumer watchdogs. After all, state insurance commissioners could find themselves regulating people with whom, in their previous jobs, they had shared lunches or rounds of golf.

However, some argue an intimate understanding of the insurance industry, from the inside, makes for a stronger regulator, not a weaker one.

“I’ve run an insurance company. I’ve been a producer. I’ve been a regulator and a legislator,” Redmer says. “I might not be the brightest guy in the room, but I know what carriers do, I know where profit margins may be hidden.

They can’t BS me.”

Most of his career in the industry, as well as his time as a regulator and legislator, Redmer says, was spent “battling the industry on behalf of insureds.…My background is perfect for protecting consumers but at the same time protecting the competitive landscape in Maryland. I’ll spend every day trying to prove it.”

Martin Grace, a professor at Georgia State University who studies the insurance industry and its regulation, also sees prior industry experience as a big plus for a state’s top insurance regulator: “Insurance is very different, and lots of even sophisticated business people don’t understand it.”

While all types of regulation can have long-term unintended consequences, insurance markets can have an especially long time frame, Grace says. “The pricing position taken today might take years to reconcile and affect the market,” he says. Keep prices too tight, Grace contends, and a state might find a decade later that most insurance companies had fled certain markets. But complying too often with insurers’ rate requests could make insurance far more expensive than it should be.

Commissioner Shuffle

So is the revolving door still operating these days? Data from the past 18 months indicate a far lower percentage of regulators parlaying their posts into industry positions, but that could reflect state-imposed delays on such moves. Time will tell.

Fifteen state insurance regulators have left their posts since mid-2013. In some cases, they or their boss (the governor) lost elections. Some retired. Some took new jobs in government or the private sector. So far, only three have taken jobs related to the insurance industry. After the Democratic nominee for governor lost, Massachusetts insurance commissioner Joseph Murphy resigned to become COO of Boston-based medical professional liability insurer Coverys, of which he had oversight while serving as commissioner. Murphy did not respond to requests for comment.

Former Pennsylvania Commissioner Michael Consedine left his post in January and has taken a job as senior vice president, deputy general counsel and executive director of government affairs at Transamerica in Baltimore, Md. He had been seated as president-elect of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. Consedine, through a spokesman, declined an interview request. And Connecticut commissioner Thomas Leonardi resigned to join New York-based Evercore Partners, an investment banking advisory firm, as a senior advisor focusing on insurance—a more tangential move into an industry over which he had no oversight. No other regulators have entered the industry in recent years since leaving office, though six have not announced any future plans.

Some are following dreams: Former Wyoming commissioner Tom Hirsig, who attended college on a rodeo scholarship, is heading up the rodeo and western festival known as Cheyenne Frontier Days. Oregon commissioner

Lou Savage left to work with emerging democracies, such as Tunisia.

Term Limits

Losing roughly a third of state insurance commissioners in less than 18 months raises the question of whether oversight at the state level is as effective as it should be.

“It’s not unusual to see a bump of people leaving sometimes,” says Bob Hunter, a former Texas insurance commissioner now dogging the industry as director of insurance for the Consumer Federation of America. “But it does take some time to get up to speed, even if they try their best.”

Former Nebraska senator Ben Nelson, chief executive of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, is not worried. “Turnover is not indicative of whether things are working or will continue to work,” he says. Nelson has made several trips through the revolving door himself. He was the assistant general counsel for Central National Insurance Group of Omaha in the early 1970s, served as insurance director in the 1977-1978 term, and then rejoined Central National to eventually become its president.

Nelson points out that, while most commission chiefs serve at the leisure of the governor or are elected, they have deputies and professional staffs who often have decades of training and experience. State insurance offices “have a deep bench of talent from which to turn for expertise and research—more than 11,000 employees at the state level and territories,” Nelson adds.

Ounce of Prevention

Talk about revolving-door issues with people in the insurance industry and you inevitably run into a steady stream of vague gossip, some of it decades old, about this person ending up with that job after making these decisions.

Much of it is impossible to pin down, and much of it might be exaggerated.

Still, the prospect of lucrative private-sector employment can be a powerful temptation that could lead to an appearance of a conflict of interest. Certain cases have raised eyebrows.

One of the more notorious cases involved Chuck Quackenbush, who was elected insurance commissioner of California in 1994 after raising hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign funds from insurance companies. He was reelected in 1998, again with substantial campaign support from the industry, but was forced to resign in 2000 in the midst of several investigations and multiple accusations of abuse of office and conflict of interest, all related to how insurers handled the 1994 Northridge earthquake. At the time, Quackenbush was considered a rising GOP star headed for higher statewide office.

The allegations included ignoring recommendations by his staff to fine three insurance companies for making payments to clients that were far lower than the actual losses caused by the quake. In lieu of fines, insurance companies allegedly made contributions to education foundations set up by Quackenbush, though most of the funds were never used for the type of earthquake education Quackenbush had described. One foundation broadcast public service commercials starring the commissioner. One fund was taken out of Quackenbush’s control by a judge.

South Carolina insurance director and then-NAIC president Ernst Csiszar was quietly suggesting to members of Congress in 2004 that the NAIC might support legislation deregulating the insurance market, Hunter says, even though most insurance commissioners favored states keeping their regulatory powers. Csiszar ultimately left his post before his terms at NAIC and in South Carolina expired and joined the other side—becoming head of the

Property Casualty Insurers Association of America, an ardent backer of federal deregulation.

Csiszar denied he had supported the deregulation measure while at the NAIC, but once he joined PCI he bluntly accused states of clinging to their regulatory powers and publicly backed deregulation.

Hunter, of the Consumer Federation of America, says the combination of temptation and opportunity is simply too powerful to ignore and he would like to see strict rules and laws that would bar such moves nationally. The tendency to come from industry can be a little worrisome, he says, but the big concern is what a commissioner does after he leaves. “It’s probably OK to come from industry. It’s not OK to return to industry,” Hunter says. “It leaves a very odd flavor in the mouth, especially if they are lobbying on insurance issues. There ought to be at least a two-year moratorium on lobbying.”

According to the National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL), 33 states have some type of revolving door prohibitions on state legislators. (Many, but not all, of those laws apply to top state officials, such as insurance commissioners.) But only eight states—Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Montana and New York—have two-year bans. Some states have one-year bans, and others impose shorter bans.

Nelson says the NAIC bylaws help prevent ethics breaches, but watchdogs say they simply aren’t as effective as strong laws.

How Much Effect

The potential for being influenced by later employment seemed so probable that Grace and a Georgia State colleague tried to quantify the effect in their research. They studied the decisions and subsequent careers of all state insurance commissioners who served between 1988 and 2004 in states where commissioners regulated the price of auto insurance.

The result: “I don’t think we found the smoking gun or the terrible things we thought we would find,” Grace says.

Overall, the impact of later employment was evident but small, and they found just slight evidence of regulatory decisions being influenced by employment in the insurance industry. But they did find stronger evidence of decisions being influenced by commissioners who sought higher office. “You would think that people wanting to run for higher office would want to be friendly toward voters and curry favor—‘Look how well I worked for you as insurance commissioner,’” Grace says. “But that’s not what we generally found. In essence, the regulator who was interested in higher office was allowing the insurers to set their own rates” to curry favor and ultimately win financial support for campaigns.

Grace says his study did not take into account the possible effect of revolving door laws. It’s not clear how many such laws affecting commissioners were in effect over the course of the study, but the NCSL said 27 states had restrictions on state legislators by 2002.

Institutional Knowledge

Regulators face a host of challenges as the industry rapidly changes, among them are the threat of cyber attacks like the one on Anthem earlier this year; the push into new markets by gargantuan international companies; the changing health insurance market; and a mind-boggling amount of data that can be used to calculate risks and rates.

The question confronting legislators, industry watchdogs and regulators themselves appears to be whether the expertise of insiders can be channeled into excellent regulation and industry solutions instead of personal gain.

The political spin on this revolving door appears to depend on your ethical and professional point of view.

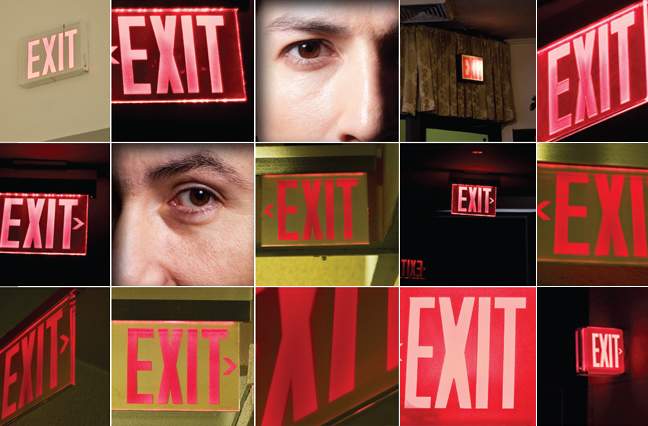

Commissioners’ Exits Since 2013

Three left for insurance industry-related jobs

Connecticut: Thomas Leonardi resigned in December 2014 to join Evercore Partners, a New York-based global investment banking advisory firm, as a senior advisor focusing on insurance.

Massachusetts: Joseph Murphy resigned in December 2014 after the Republican gubernatorial nominee was elected in a very Democratic state. He joined Boston-based medical professional liability insurer Coverys as its new chief operating officer.

Pennsylvania: Michael Consedine resigned in January 2015 after the GOP governor was denied reelection. He joined Transamerica as senior vice president and will head up the company’s government relations at the state and federal level.

Three left for jobs unrelated to insurance

Alaska: Bret Kolb left in December 2013 to lead business development for Victory Ministries of Alaska.

Oregon: Lou Savage left in June 2013 to join the American Bar Association’s Rule of Law Initiative in Tunisia.

Wyoming: Tom Hirsig resigned in January 2015 to head Cheyenne Frontier Days.

Two left for other state government posts

Michigan: Kevin Clinton left in October 2013 to become state treasurer.

Texas: Julia Rathgeber resigned in January 2015 to serve as deputy chief of staff to the new governor.

Six have not announced future plans

Arkansas: Jay Bradford left in December 2015 due to a new governor.

Colorado: Jim Riesberg left office in July 2013, citing personal reasons.

Illinois: Andrew Boron left office in January 2015 after the Democratic governor was defeated last year.

Kansas: Sandy Praeger did not seek reelection and left office in January 2015. A moderate Republican in an increasingly conservative state, she and would have had trouble surviving a GOP primary. The divisions in her party were highlighted by her endorsement of the Democratic nominee for commissioner, who lost.

Maryland: Therese Goldsmith stepped down in January 2015—four months before her term expired—after the Democratic gubernatorial nominee unexpectedly lost in this heavily Democratic state.

South Dakota: Merle Scheiber resigned in December 2014 for personal reasons.

One retired

Idaho: Bill Deal retired in December 2014.