Whether You See It or Not

Dana Lariviere is a self-described ultra-conservative with no experience with substance use disorder.

His theory on the topic?“You stuck the needle in your arm. This is your problem.”

While employers often don’t recognize it in the workplace, about 9% of working adults struggle with substance abuse.

One 2020 survey found 49% of full-time workers were drinking or using drugs in a way that impacted their work.

Workers with substance use disorders miss an average of 24 days of work annually.

So it was more than a little surprising when Lariviere, the founder and CEO of Chameleon Group, in Dover, New Hampshire, went to bat for a former employee who was recovering from her addiction to heroin.

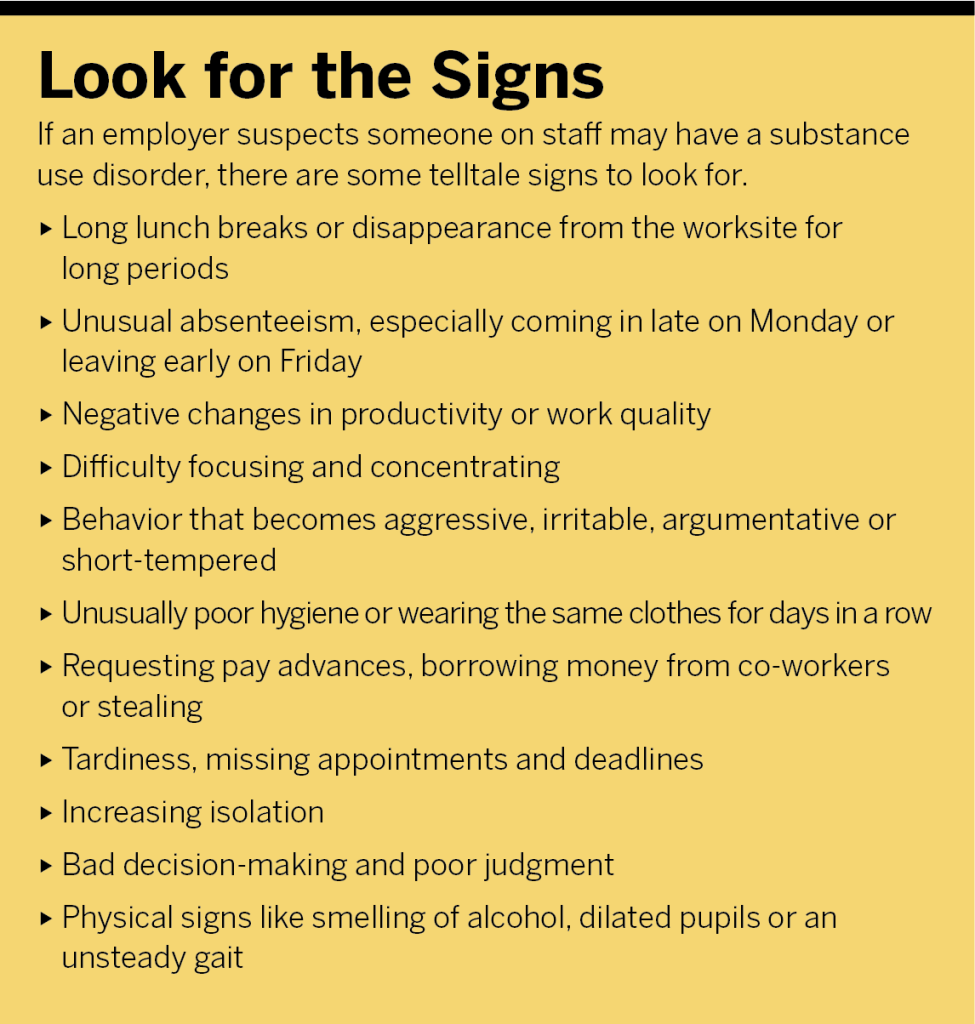

The woman was unreliable, often leaving early on Fridays and arriving late on Mondays, not unusual at Chameleon Group, a sales and business development company where turnover was high. The employee was fired around 2015. A couple of years later, she phoned him, asking for her job back. She told him she had been addicted to heroin while working at Chameleon. She was in recovery, she told Lariviere, and she wanted to return to the company to make amends for her poor performance.

“I was gobsmacked,” Lariviere says. “We are a smallish company of about 45 employees, and I had always prided myself on knowing what was going on with people. But I had no clue. I was clueless.”

When he told his management team her story and that he wanted to give her another chance, they pushed back. But as founder, president and CEO, he put his foot down, and, in spite of their reservations, he let her return. He let the woman know she was on thin ice and that management was actively rooting for her failure.

If they indeed were, they were disappointed.

“She crushed it,” he says. “She ended up becoming a member of the management team.”

Like Lariviere, many employers are unaware that an employee might have a problem with substance abuse. But about 9% of working adults in the United States struggle with substance use disorder (SUD), according to the National Safety Council. Most cases concern alcohol abuse, with marijuana and prescription opioids next. Though substance abuse is more commonly found in industries such as construction, service work and transportation, no sectors are untouched. The National Institute of Mental Health describes SUD as a mental disorder “that affects a person’s brain and behavior, leading to a person’s inability to control their use of substances such as legal or illegal drugs, alcohol, or medications.”

Whether employees are abusing alcohol or drugs in or out of the workplace or are in recovery, employers should pay attention. By supporting these workers, employers can reduce healthcare costs, absenteeism and turnover and engender fidelity among a group of workers who can be assets when given the opportunity.

“It’s the right thing to do for the employees and the business,” Lariviere says. “And how often in the world do you get to do something that is the right thing for everyone?”

Ins and Outs of Substance Use Disorder

The first thing to understand about substance use disorders is how widespread they are, particularly since the pandemic.

In its 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that more than 138 million people Americans age 12 and older were using alcohol. Of those, 44% were classified as binge drinkers. The same study found that 21% of adults (nearly 60 million people) had used an illicit drug in the past year—in most cases, marijuana.

“It’s incredibly common,” says Daniel Jolivet, a licensed clinical psychologist and workplace possibilities practice consultant at The Standard, an insurance and financial services company based in Portland, Oregon. “When we look at alcohol use disorders, where people are using it to the point that it has an impact on the workplace, the numbers are quite high.”

When alcohol.org surveyed 3,000 U.S. adults working from home in 2022, 32% of respondents said they were more likely to drink during working hours. The Standard commissioned a survey in 2020 and found that 49% of full-time workers were drinking or using drugs in a way that was impacting their work.

Even when employees are not actively using substances during working hours, alcohol and drug abuse can impact the workplace. According to the National Safety Council, a typical employee misses about 15 days of work a year outside of vacation and holidays. Workers with substance use disorders miss an average of 24 days a year. And while 22% of employed people have had more than one employer in the previous year, those with substance use disorders are 40% more likely to have multiple employers in one year. In white-collar industries, it is estimated that employees with untreated SUD cost employers more than $14,000 annually.

But for all the data, it’s important to understand that people with SUD should impact a workplace no differently than someone with other chronic health conditions.

“This isn’t a choice; it’s not something people choose; it’s a chronic condition,” Jolivet says. “It’s chronic but often invisible, and it is treatable—about 60% of people with addiction will fully recover and live ordinary lives.”

Upwards of 85% of people with AUD (alcohol use disorder) or another SUD go months, even years, without abusing alcohol or other substances, then relapse, need treatment and return to sobriety, he says.

“At its heart, substance use disorder is a health condition, and where employers get in trouble is when they bring in social stigma,” says Ashley Handwerk, vice president of human resources for Miltenyi Biotec North America, a biomedical research company founded in Germany. “Like any other health condition, employers have to understand its impact on employees and legal and regulatory spaces, just like someone who has diabetes or cancer.”

Active Recruitment

DCI Furniture is a hardwood furniture maker in the rural community of Lisbon, New Hampshire. Chandelle Whitney, its director of human resources, said her employee base was particularly susceptible to the opioid epidemic. A couple of years ago, the company decided to begin supporting—and then actively hiring—people with substance use disorder.

At the time, DCI had a high attrition rate and terrible attendance. On any given Monday, 20 of the 100 or so people on the factory floor might call in sick. The company couldn’t fire that many people because of the difficulty in finding reliable replacements.

So Whitney began to intervene with the workforce. She started working one on one with people with substance use disorder. She had some early success, so DCI brought in more support. Just before the pandemic, the company received a state grant that enabled DCI to fund an on-site counselor whom employees could talk to—confidentially and on the clock. When the grant ran out, Whitney began looking for other options and landed on the state’s Recovery Friendly Workplace program, which works with companies to put together resources for people in recovery.

After about 18 months and lots of work, Whitney says, her workforce became much more reliable. This empowered the company to actively begin hiring people with substance use disorder, including those living in a nearby sober house who had recently been released from jail. They even purchased a bus in order to drive people to and from work each day. And the change has been dramatic. Now, Whitney says, on a typical Monday only two DCI employees call in sick.

“It’s happening whether you want to see it or not,” she says. “The question is do you choose to address it or ignore it. It’s been positive for our business to address it. We have a more stabilized workforce and better morale and feel like we are generally doing good for society.”

Chameleon had a similar experience. After the success of the woman who returned to work for them, Lariviere asked her if there were others with SUD who needed jobs. She told him to look out the window—a local recovery group shared their parking lot.

“This journey started for us there, and we actively went out and started recruiting folks,” Lariviere says. “They were all essentially unemployable because the stigma was so huge.”

The recovery organization became a resource for Lariviere and directed him to a nearby drug court, which offers an alternative to incarceration for people with SUD who find themselves in the judicial system.

“We told them,” Lariviere says, referring to court officials, “if you have people that are progressing and looking for employment, we’re hiring.”

Strong Employees, Stronger Companies

Employing people with substance use disorder, whether purposefully or not, may seem risky for many employers. The employees may seem unreliable, and statistics bear that out—except when compared to other chronic conditions.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, people with substance use disorders have a lower rate of relapse than people with either hypertension or asthma: 40% to 60% for those with SUD versus 50% to 70% for those with the latter two conditions. For SUD, like other chronic health conditions, relapse can merely be a sign that treatment needs to be modified or renewed. The institute notes that treating people for SUD or for similar chronic conditions should be thought of as management, not as a cure.

And the National Safety Council found that employees who miss the least amount of work—about 10 days annually—are those in recovery.

“Work provides a linchpin of value because a lot of people with SUD have lost their families, kids and homes and have to build back up a sense of self-worth,” Lariviere says. “And being valued really, really helps. They are very loyal. They are not likely to jump ship for someone down the road who pays $1 an hour more, because we understand what is going on and work with them.”

Whitney says they have had an 80% retention rate with their employees since they began actively recruiting last spring. Jolivet said an axiom in his field is that someone with SUD or AUD will lose all they have before they lose their job. It tends to be the last thing they hold on to for a sense of meaning.

Greg Young, director of employment support services in the Pennsylvania office of Unity Recovery, a community organization supporting people with mental health and substance use disorders, says Unity Recovery works with employers ranging from mobile food trucks to cleaning companies and offices. He often hears the trope that employers worry whether someone with SUD can work in a business in which they would be handling cash or pricey inventory, because they are more apt to steal.

“We say no, someone with SUD is not necessarily any more likely to steal, leave early or come in later than anyone else,” Young says. “After they’ve been in recovery, once they hit five years, they are as likely to relapse as anyone else is to develop a new substance use issue.”

Managing A New Population

Whitney acknowledges that, in the beginning, managing people with SUD and AUD fell on her shoulders. Her years of regulatory management had to be set aside for intense personal contact with the workforce. And because people with substance use disorder rarely disclose it voluntarily, it can be difficult to discern who is dealing with it in the workplace.

“Addiction is a disease of isolation and shame, and stigma just makes the isolation worse,” Jolivet says. “Stigma actively makes addiction worse because people will conceal what they are going through.”

That’s why one of the main tenets of Unity Recovery is openness. When people are encouraged to disclose when they need help—without the threat of being fired—they are more likely to seek treatment and ask for accommodations.

In a 2019 report by the National Safety Council, 75% of surveyed employers said their workplaces had been impacted by the opioid epidemic, but only 17% felt their organization was “extremely well prepared” to deal with opioid use in the workplace.

Handwerk, Miltenyi Biotec’s HR officer, says employers should think of SUD as one of the many health conditions they need to manage. “For human resource teams, they aren’t trained in recognizing, de-escalating and supporting people going through any health crisis,” she says. “They all should be. Whether it’s having a panic attack or SUD issue, they should be able to support employees through that situation.”

Handwerk says human resource professionals should be lifting much of the weight in this space. It’s their job, she says, to come up with recommendations that balance supporting the employees and maintaining the quality, performance and safety standards of the employer.

For employees in recovery, Lariviere gets a release of information signed so the employee’s parole manager, psychiatrist or other professionals can talk with Chameleon managers about the employee. If someone says they need to leave work for a court date, Lariviere can make a phone call to confirm. The company also publishes its workplace drug policies and has everyone sign the employee handbook to show they are aware of what is expected.

“There is no stigma here, but there are also no excuses,” he says. “The rules are straightforward and based on performance and honesty. We know that relapse is part of recovery, so just come and tell us. If you tell us and go to recovery, you are eligible for rehire when you are done.”

Even with all the accommodations, however, people should never be allowed at work actively impaired. If someone comes in unable to work, Whitney asks them to leave and, if necessary, gives them a ride home.

“We don’t immediately fire people, because we understand it is a health condition,” she says. “But we are a wood shop, and we have saws. People can’t work in that condition.”

If it becomes a problem and people are having too many issues, Whitney asks employees to sign a last-chance agreement. The voluntary agreement says the person must receive regular drug tests at the nearby outpatient rehabilitation site and DCI can get the results (they don’t drug test their workforce normally). If those tests come back positive, DCI can terminate a person’s employment. Whitney says the company has had to do that just twice in the past three years.

Limitations and Restrictions

Substance use disorders are considered disabilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Employers can support an open and honest conversation with workers about SUD, but they cannot ask employees to disclose if they have a substance use disorder, are in recovery or are in treatment. If employees reveal any of that, they automatically fall under ADA protections.

The ADA states that people with AUD or SUD are entitled to accommodations, as long as they are able and qualified to perform their jobs. Illegal drug use isn’t protected under the ADA, but people in recovery cannot be discriminated against unless a drug test discovers they are actively using drugs.

Jolivet tells managers to meet privately with an employee if they suspect the employee might be dealing with SUD or AUD. He advises them to talk with the employee about the problem behavior and ask if there is anything the employer can do to help prevent it in the future. Some people might say they are dealing with an issue that could include AUD, so it’s difficult to get up in the morning. At that point, an employer can advise employees to talk to someone in human resources and refer them to the employee assistance program (EAP).

“If someone is using heroin, which is more common than one might think in a work environment, they aren’t going to say, ‘I’m bad with mornings because I’m shooting up at night,’” Jolivet says.

According to the ADA, employers are not required to accommodate the addiction—employees can’t come to work under the influence or use drugs or alcohol in the workplace—but employers must accommodate the limitations and restrictions recommended by a treating healthcare provider.

An example of a limitation would be that an employee receives a one-hour lunch break at the same time every day, without exception, so they can attend a support group like Alcoholics Anonymous. Jolivet says people with addictions tend to have problems sleeping—even when in recovery—so a later start time is a common option to manage that. A restriction may be that a person in sales doesn’t have to go to bars to meet clients, so they have sales meetings only on the golf course or at places where alcohol isn’t served. Or a person can skip a mandatory meeting or a holiday party if people are imbibing.

“Those accommodations don’t cost the employer anything,” Jolivet says. “Employers tend to overestimate the cost of accommodating someone, particularly when you consider firing them or they quit. The cost of replacing a worker is about one third of their salary.”

Better Benefits and Programs

Accommodating the needs of employees with SUD and AUD isn’t completely altruistic. By working with them, businesses can retain institutional knowledge, reduce healthcare costs and decrease absenteeism.

Whitney recently spent her lunch hour driving an employee to court and back, enabling the employee to be gone an hour instead of the whole day. “If I hadn’t driven her, I would have had to figure out how to replace her that day,” Whitney says. “She’s a good worker—we love her—she just made some mistakes in her past.”

There are several similar employees at DCI, Whitney says. The company president is paying for outpatient rehabilitation for one worker who, when he’s not in recovery, doesn’t come to work. “He is so valuable when he’s sober,” she says. “He’s been at the company for 15 years, has no license and walks to work.”

There are a wide range of accommodations that employers can make to support people with SUD and AUD and ensure the workplace is safe and employees are supported and healthy.

One is to have solid drug-free workplace and conduct policies. Getting those in place helps protect an employer and provides clear guidelines for workers. Some employers offer Naloxone training so people understand how to treat someone who has overdosed on opioids.

Internal buddy systems, in which one person acts as a mentor or just someone to talk to, can be an effective form of peer support. DCI hires a counselor to come to the business once a week, for two hours, to talk with employees who are interested in creating a recovery program. The counselor also directs employees to local resources such as

AA meetings or assistance getting into rehabilitation.

To show a company is supportive of people with SUD and AUD, companies can offer their site to host AA or Narcotics Anonymous meetings. “Hosting meetings after hours is a good way to signal to the entire workforce that this is a part of life and we don’t shy away from it or associate shame with it,” Handwerk says. “We support people trying to address this condition.”

Robust healthcare and benefits are essential for supporting the entire workforce and something that an employer can control. Jolivet recommends annual health risk assessments. Though results are confidential, such assessments can provide an aggregated look at the number of people reporting alcohol, illicit drug or prescription drug misuse. This gives an employer a general idea of what is going on in the company.

Jolivet is also a fan of employee assistance programs. He concedes they are underused but says they are successful and cost effective. One way to increase employees’ participation in such programs, he says, is by having an anti-stigma campaign regarding SUD and AUD. “If people have less shame and are less fearful,” he says, “they are more likely to use EAPs.”

A pharmacy benefit plan should cover all medications used for medication-assisted treatment (MAT). There are several options available for MAT, and Jolivet says some pharmacy benefit managers don’t cover them all in order to save money. But the drugs are not interchangeable—some are offered at different locations and prescribed by different kinds of providers. Coverage should be robust, and a company should ensure the medications are sold near employees so they don’t have to travel far to get them.

There should also be enough mental health providers—and ones that offer MAT—on company health plans. A health navigator can assist in getting employees to the right providers and the necessary treatment.

Leaning In on Support

Something else to consider for people with SUD and AUD—for all employees, really—is ensuring they have basic living needs met.

“Something you don’t think of with people in recovery is they have lost a significant amount of capital,” Young says. “They may not have a place to live, have lost their license and may be paying attorney fees for a DUI.”

He says employers should think about providing workers with a cell phone or a reference letter to get an apartment. Some workplaces he has trained raised salaries to start at $15 an hour for most positions. Paid time off is helpful when people need time for court hearings, medical care or therapy.

Handwerk says employers should know how to help people find a shelter if they need someplace to stay and get other housing assistance or help with utility bills. Chameleon opened a food pantry for people in recovery. Company managers purchase extra groceries when at the store, and they use that to fill the pantry. It’s now available for any employee needing some help.

“If you are in recovery, you can find out where to get yoga or spin classes, but you can’t get transportation or clothes or a place to live,” Lariviere says. “People need a roof over their head, and they need to eat.”

One of the most important aspects for businesses that become what Unity Recovery describes as “Recovery Friendly Workplaces” is recreating their culture. Young says most businesses they work with include a nondiscrimination policy for mental health and recovery status in their employee handbooks. Employees have to feel comfortable they won’t be fired if they discuss their substance use or recovery. He recommends a supportive supervision model, in which someone in management spends time with employees weekly or monthly to talk about anything they want—issues with work, life or family.

“We notice that in a supportive supervision model, when someone is struggling, they are more likely to come to you for support or information,” Young says, “where at a traditional workplace, they might feel like they would get into trouble if the employer found out.”

These kinds of offerings can be beneficial for the greater workforce and shouldn’t single out people with AUD and SUD. When Lariviere first began actively hiring from the court and recovery programs, he would bring them in weekly to talk about how things were going. He thought he was being supportive.

“One day,” he says, “someone tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘You are treating us differently than everyone else, and it’s stigmatizing us more.’ I hadn’t even considered that.”

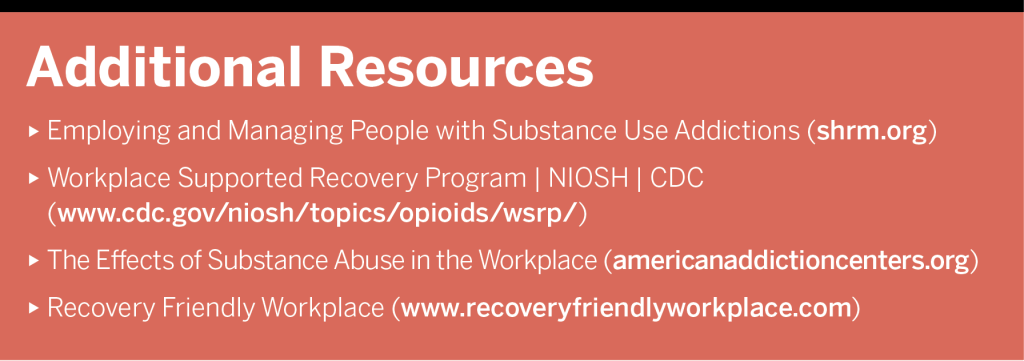

Where to Look for Help

Employers play a critical role in the prevention of alcohol and substance use disorder among employees and in supporting those in recovery. But it’s not something that will be intuitive for most businesses, nor will they see a change overnight.

“We saw that employers needed support to become recovery-friendly employers—they can’t do it on their own,” says Jillian Berk, director of research and evaluation at Mathematica, a data analysis company that performed a literature review in 2020 looking at the role of the workforce system in addressing the opioid crisis.

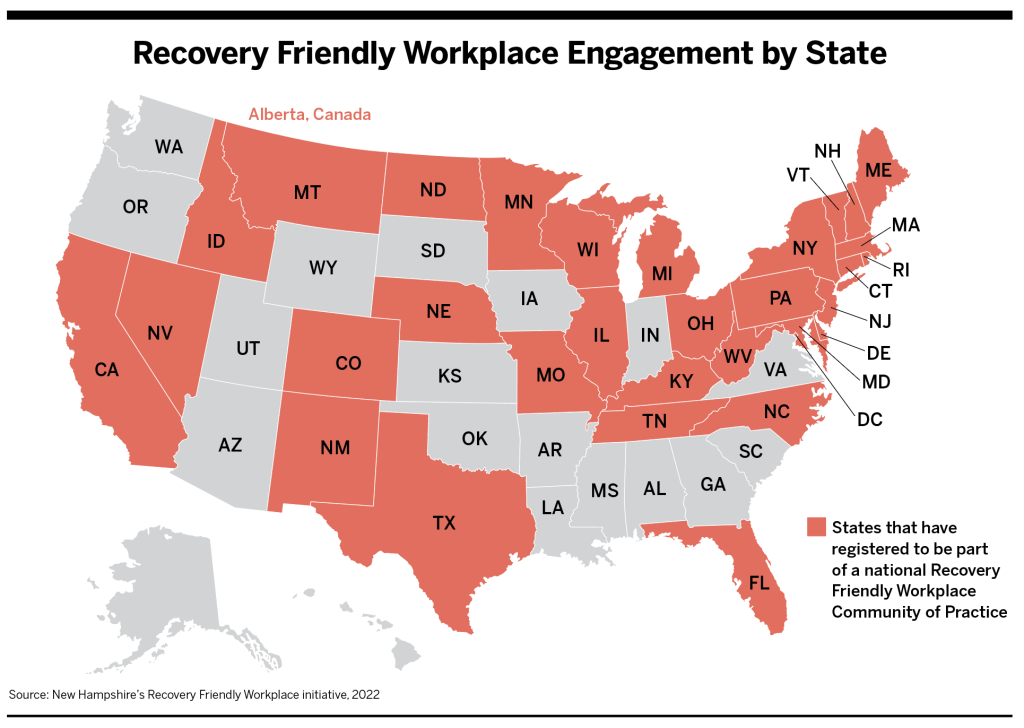

Recovery Friendly Workplace organizations offer great resources for employers. The initiative was first launched in 2018 in New Hampshire by Gov. Chris Sununu and has spread to more than 20 states including Ohio, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania and Colorado.

There were 25 early adopters of the New Hampshire program, which now works with more than 300 employers in the state, says Samantha Lewandowski, program director for New Hampshire’s Recovery Friendly Workplace, which works with Granite United Way. The organization works to train companies’ leadership and rebuild culture. They provide policy templates and a one-page checklist that employers follow to be designated as a Recovery Friendly Workplace.

She emphasizes the importance of getting the word out by having employers make a declaration of their commitment to being recovery friendly through email blasts and meetings.

The New Hampshire entity helps employers work with systems already existing in their communities, such as 211, United Way’s national phone number to connect people with nearby resources like housing and food assistance.

Local recovery support organizations can offer a lot of information to employers as well. Some insurance companies provide training on recognizing and assisting people with mental health conditions and substance use disorders. And disability insurers may be able to work with an employer to discuss stay-at-work and return-to-work programs for people with SUD. Jolivet says The Standard has a unit dedicated to this space.

Many of the resources and supports that are available for businesses help not only people with SUD but also those with disabilities or other health conditions. Chameleon is a Recovery Friendly Workplace, but Lariviere says the goal is really to be employee friendly.

“If an employee came to you and said they were just diagnosed with cancer, you wouldn’t say, ‘I’m going to whack you,’ but that’s what people do with substance use disorder,” he says. “I don’t know anyone who hasn’t been touched by this. I have employees who I know don’t have it, but their kid or their husband or someone else in their family does.”