In Search of Mental Health Equity

As president of the Maine Employee Benefits Council, Ken Ginder likes to offer free programs to members to keep them abreast of goings-on in the industry.

Each year, the U.S. Department of Labor releases a report providing information on health insurers’ compliance with the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. This year’s report was the first one published since health insurers were required to complete comparative analyses to ensure they are complying with the law.

Starting this year, the federal government is prioritizing equal treatment for mental and physical health conditions.

The recently passed Consolidated Appropriations Act created a comparative analysis that insurers must use to confirm compliance.

Though they might lack sufficient information, self-funded employers are responsible for conducting comparative analyses.

Ginder, a partner in the employee benefits and executive compensation group at law firm Verrill, says he thought this might be a good time to bring people from the Department of Labor’s Boston office in for a presentation. Without mentioning the report, he asked what their enforcement priorities were for 2022. Their response? “Parity is it.”

“At that point,” Ginder says, “I knew this was a topic that deserved attention.”

When releasing the report in January, U.S. Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh, who has talked openly about his own battle with alcohol abuse and treatment in the 1990s, penned a companion blog on the department’s website. There, he noted the federal government is prioritizing equal treatment for mental and physical health conditions. The department, Walsh wrote, will “ramp up enforcement.”

“All of this adds up to something that should be taken seriously,” Ginder says. “The Department of Labor has a tool to help with enforcement, and insurers need to do a detailed and complex analysis and state if they are in compliance.”

More Than a Decade of Work

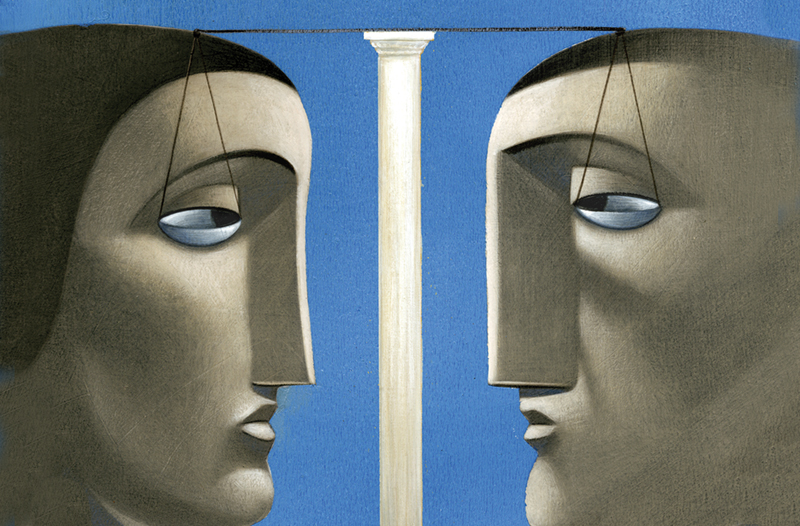

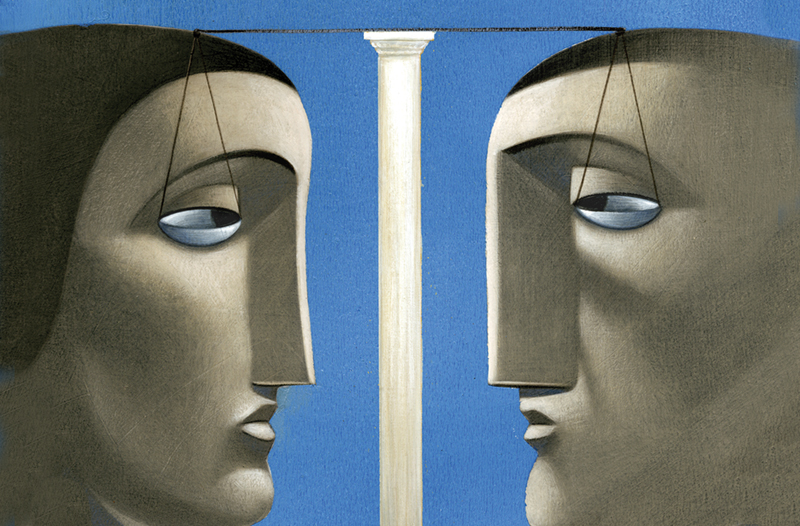

The need to create equality between coverages for physical health conditions and mental health and substance abuse treatments began with the passage of the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. This law banned large group health plans from imposing lower annual and lifetime limits on mental health than they did on physical conditions.

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act expanded those protections, requiring plans that offered mental health benefits to have the same benefit limitations for both physical and mental health, and it included substance abuse disorders for the first time. This was implemented for plans in the 2010 benefit year. The Affordable Care Act expanded parity requirements to smaller employers and individual coverage.

For a dozen years, insurers were supposed to be complying with these laws. But it wasn’t until the recently passed Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) that a tool was created—a comparative analysis—that insurers are required to use to determine if they are complying. This tool also gives the federal government a better way to gauge compliance and enforce the law.

The analysis compares non-quantitative treatment limitations, which are non-numerical benefit limitations. These treatment limitations include precertification for and appropriateness of services, prescription formulary design, step-therapy protocols, and restrictions based on provider specialty.

The turnaround between the CAA’s passage and when insurers had to create the comparative analyses was extremely quick by congressional standards. The bill went into effect in December 2020; the Labor Department said insurers needed to have comparative analyses prepared by February 2021; and the department began asking for copies of the documentation in April 2021.

“It was a surprise to many that one of fastest deadlines in [the CAA] was the parity compliance requirement,” says Jessica Waltman, vice president of compliance at MZQ Consulting, a benefits compliance advisory group in Pikesville, Maryland.

“The premise was insurers should have already been doing this,” she says of insurers’ role in checking for parity. “But no one had really done it before.”

Waltman says the Obama administration pushed for greater parity and occasionally sent information to consumers to understand their rights. A few state health commissioners have been diligent about parity for plans in their states. Other than that, she says, she has mostly seen “widespread noncompliance” among plans.

“It was more of a rubber-stamp scenario,” Waltman says. “A few consumers were filing complaints, and there were a few investigations but not a lot. It wasn’t like I encountered a lot of plan sponsors who didn’t want to provide equity, but no one was really worrying about compliance.”

Enforcement By Scale

The irony here is, the coverage details and decisions being made in these plans are done by the vendor that developed the benefits policies that are being enforced. But the responsibility to conduct a comparative analysis falls squarely on the self-funded employer, who often has no input or information needed to produce the document.

Jay Kirschbaum, benefits compliance director and senior vice president at World Insurance Associates, based in Washington, D.C., says self-funded employers are relying on carriers, third-party administrators and pharmacy benefit managers to determine the right coverage. “But the Department of Labor doesn’t have any oversight authority on the carriers,” Kirschbaum says, “so they are using employer plans to analyze treatment restrictions and limitations.”

As a result, says Jordan Smith, a partner at South Carolina-based Self Insured Reporting, “there’s lots of finger pointing, and the DOL doesn’t have a direct line of enforcement to the vendor. They can only enforce at the employer plan sponsor level. So what we have seen is the potential for the state level to get involved with vendors and push enforcement, and they have recourse at that point, once it is referred to the state by a federal agency.”

That process leads to enforcement by scale, and the side effect is additional investigations of plans related to those insurers with plans found to be noncompliant, Smith says. By the end of last year, when he received calls from clients being audited, he could tell who the third-party administrator was going to be based on the originating area of the investigations.

In fact, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report noted that one of the initial purposes of the audits was to “identify and focus on service providers that are in a position to enact widespread change for an entire line of business” and large numbers of plans. This happened when the Employee Benefits Security Administration discovered a Los Angeles-based service provider that was excluding behavioral therapy for autism. This organization administered claims for hundreds of plans nationwide, and the L.A. regional office was able to make a large impact by requiring the insurer to change its benefits.

Smith notes that the government is asking for a large amount of information; is providing somewhat abstract guidance; and has not provided a tangible example of a final comparative analysis. While insurers are undoubtedly behind the eight ball when it comes to parity, they have also never had to articulate their decision-making in this way.

“This process is the definition of a dynamic landscape from a compliance perspective,” Smith says. “Employers need to be prepared that a lot of it is about making a good-faith effort as opposed to starting from scratch when that DOL audit letter comes through.”

Regardless of the difficulty of putting together a comparative analysis or the lack of clarity in the rule, those that aren’t compliant will face consequences. And for self-funded plans, employers are the fiduciaries, so they are the responsible party.

Widespread Noncompliance

The Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) is the organization with enforcement jurisdiction over group health plans. In total, between Feb. 10 and Oct. 31, 2021, the administration sent 156 letters to plan sponsors requesting comparative analysis; the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has sent out 15 letters since the enactment of the CAA, according to the 2022 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report to Congress. This report detailed the EBSA’s initial actions and compliance findings in the first year of the Consolidated Appropriations Act.

About 40% of all plan sponsors responded to the EBSA with requests for filing extensions. Of those that sent in analyses, none supplied sufficient information, according to the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report. The administration sent out 99 letters requesting more information because there wasn’t enough to determine if non-quantitative treatment limitations were appropriate and because comparative analyses were incomplete. The administration sent out 45 determination letters letting vendors know their plans were out of compliance with the parity law.

Most experts agree that plan fiduciaries weren’t intentionally being discriminatory. Nor were vendors just blindly ignoring the law. What likely tripped up most plan sponsors are several complex factors that go into both ensuring that a plan complies and creating a complete comparative analysis.

Waltman said MZQ Consulting began helping clients with comparative analyses in April and most of them were already being audited by the Department of Labor.

“People started panicking,” she says. “No one had started doing it, so they hadn’t reviewed plan documents and none were compliant.”

One common occurrence Waltman saw among her clients were vendors that had plan documents “Frankensteined” together. Some vendors were used to tacking on additions to the plan language over the years as laws changed, instead of amending the entire plans. Some vendors used templates based on other insurers’ reports when they were uncertain how to put parts of a plan together. None of this plan wording was based on clear standards.

Waltman cites provider reimbursement as an example. If a vendor decides to reimburse providers at 125% of Medicare rates, the vendor has to show how it came up with that number. “The provider took it” is not considered an acceptable answer, she says. Or plans can include cost as a standard for determining if a treatment should be excluded. But they can’t exclude a particular treatment just by saying it is “high cost.”

“They have to say what ‘high cost’ means,” Waltman says. “So, if over $1,000 is their answer, then how did they get to that? Maybe they did a survey of their claims data and 90% of the claims were under $1,000, so they decided that was the expensive mark. That’s the kind of process they have to do for all of the different factors that might be involved.”

The comparative analyses must be so detailed, Kirschbaum says, that vendors can’t just say how decisions were made; they have to document who made them. If a committee was used to determine if something is going to be covered, a vendor must give detailed information on all of the people in that group.

“They get granular in respect to these comparative analyses,” Kirschbaum says. “To know what is exactly needed is really tough.”

Trying to determine what the Department of Labor considers an adequate response has produced “a lot of back and forth,” says Nick Karls, compliance director at Holmes Murphy. “So I think the DOL is still working through what their audit process looks like,” Karls says. “When you look at the depth of information that they’re requesting, it would make sense that it would take some time for them to refine that process. One of the things that we talk about with the client is understanding that a lot of this is out of their control. And while the requirements absolutely apply to the plan, there’s no way around that, I don’t think that the DOL and the agencies are blind to the fact that the most the client can usually do is ask that the TPA provide some sort of confirmation.”

Frequent Offenses

Smith, from Self Insured Reporting, says his organization is working on comparative analyses for 110 TPAs. He has yet to see a plan that didn’t have issues, large or small.

Something Smith frequently sees—a problem noted in the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report—are exclusions for eating disorders. He has seen outdated plans excluding eating disorders from services except in the case of a mental health condition. But, anorexia and bulimia are, by definition, mental health conditions.

“Some of that kind of stuff is hanging around because the plan language isn’t updated like it should be,” Smiths says.

In fact, limiting or excluding nutritional counseling for mental health conditions was one of the most common deficiencies noted in the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report. The report detailed an investigation into a health insurance issuer in New York. The vendor had two plans that offered nutritional counseling for people with conditions like diabetes or heart disease but not for beneficiaries with anorexia, bulimia or binge-eating disorder. The New York regional office of the U.S. Labor Department found the plans to be out of parity and worked with the issuer to amend its plan documents for these plans, which cover 1.2 million people, according to the report.

None of the initial comparative analyses received from vendors were complete, according to the Employee Benefits Security Administration. Here are the most common deficiencies the EBSA listed.

- Failure to document comparative analysis before designing and applying the non-quantitative treatment limitations (NQTL)

- Conclusions lacking supporting evidence or explanation

- Lack of meaningful comparison or analysis

- Nonresponsive comparative analysis

- Documents given without explanation

- Failure to identify the benefit classifications affected by NQTL

- Analyzing only portions of NQTL

Two other areas that Smith saw out of compliance—both were listed as frequent offenses in the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report—were excluding applied behavioral analysis for the treatment of autism spectrum disorder and issues regarding medication-assisted treatment for substance abuse disorders.

Medications like methadone and naltrexone, in combination with therapy or alone, have been widely studied and shown to be effective for treating opioid abuse. A large plan covering more than 7,500 people in New England excluded both medications for opioid abuse. The issuer did not have a similar restriction for medical/surgical medications and had no comparative analysis regarding its decision. The plan was required to remove the exclusion, notify participants and take corrective action retrospectively, according to the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report.

“Some plans are allowing medication-assisted treatment (MAT) when it’s post-procedural but not for substance use disorder,” Smith says. “They also have to consider thinking about where it is more experimental, like the use of LSD for PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. That’s a different form of substance use, but plans should be adding clarity to how they are addressing MAT.”

The final area Waltman notes as deficient for many plans is stringency testing. Insurers might not notice they have a discrepancy in areas like provider reimbursement or claims denials until they do an operational test. They might find a psychiatrist is being reimbursed less than a speech therapist for no reason. Or they may have higher rates of denials for prior authorization on the mental health side than the medical side.

“There is a requirement that groups have this information in written documentation,” Waltman says. “They need to test to see what they are doing day to day, to look at de-identified claims data to see what is going on.”

Employer Prep

So what should an employer do to be best prepared? Waltman urges self-insured employers to request a copy of the non-quantitative treatment limitations (NQTL) comparative analysis from the vendor. This should be done in writing so employers have documentation that they requested the information. Most likely, what employers will get in return is general information, but Waltman says they should see a full report, along with stringency testing for their specific plan.

Unfortunately, response from vendors—much like what was seen in the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report—has been varied. The vendor might not respond to the employer’s request or might take a long time to do so. Employers may reach out to vendors only to find out that an analysis wasn’t prepared nor was it in the vendor’s contract to complete one. An employer may have several vendors to deal with—one for medical, another for mental health and a third for prescription drugs. Completing an analysis may require synthesizing information from all these vendors.

Some vendors may be working with administrative services groups that are performing their comparative analyses. A third-party administrator may be able to refer employers to that entity, which could charge for the report. Waltman says insurers may say, “Come back when you’re audited, and we’ll help then.”

“Unfortunately, you are going to get what you get,” she says. “This isn’t something that can be ‘whipped together,’ so if they say they’ll do that, don’t believe them.”

Waltman says employers should do the best they can to have some paperwork in case of an audit. She recommends keeping a file in which an employer records each contact with the plan vendor and updating the file each time the employer reaches out. If a vendor can’t create an analysis, that should be recorded and considered in future plan years.

“Employers should take into account that there was a legal requirement and the plan couldn’t, or wouldn’t, help,” she says. “Or maybe they charged a fee for it or you found out it was out of compliance by a lot or they didn’t change the plan when it was out of compliance and was discriminatory. You should weigh if you are alright with that or if you want to go with someone else next year to do this.”

Most employers don’t have the information or human resources to do their own comparative analysis. But there are some tools out there that could help piece together some documentation in case of an audit. The U.S. Department of Labor published a self-analysis checklist, which isn’t a template for the analysis but provides helpful guidance on the information needed. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act report provides ample details about what the EBSA found in its initial outreach and could show employers common problem areas on which to focus. DOL regional offices, responsible for enforcement, also do a lot of outreach, and they could be a resource to help with compliance. Finally, if a vendor is stonewalling, lawyers or consultants who specialize in this space can create an analysis.

If an employer does manage to get some information from its vendor or looks to outside help, this is not a one-and-done function. Plans change annually, and a comparative analysis should be up to date. Annual reviews may not be necessary, but a comparative analysis shouldn’t be more than a couple of years old, according to Waltman.

While they might not have a horse in the race, brokers should also be aware of the landscape. Mark Combs, CEO of Self Insured Reporting, says brokers should know what is going on with their plans and advocate for clients to work with their carriers to ensure proper documentation is available.

“I think a lot of it is just continuing to not only discuss it with our clients to make sure they understand the realities of the situation,” Karls, of Homes Murphy, says, “but it’s also continuing to reach out and request that our TPA partners and our PBM partners continue to move that ball forward so the solutions they’re providing to clients are ones that will help our clients comply with the law.”

At the end of the day, Karls notes, “I think just about everyone agrees that everything behind it makes sense.” What’s difficult for employers, he says, is the costs they are going to incur trying to make it happen. “Whether it’s to try to get someone to perform the analysis for them or paying extra to the TPA, having a baked-in cost to have them work on this behind the scenes…I think a lot of employers look at that and go, ‘This was unnecessary to put it on us in this way when we have virtually no control.’”

Facing Consequences

Prior to 2021, there was not a lot of enforcement in relation to parity requirements. Kirschbaum, from World Insurance Associates, says fewer than 75 actions were investigated in 2021 and only 14 problems were found. Most investigations prior to this year occurred when a plan participant complained to a DOL regional office about a benefit denial. The department would investigate the plan to see if there was a systemic issue, and, if there was, noncompliant plans were required to pay benefits that were improperly denied and fix the problem moving forward.

But this new tool has changed the rules for investigation and enforcement.

“Everybody has stories where they can’t get in to see a counselor for one reason or another, and this is trying to address it,” Ginder says. “This is all about compliance with a law that has been on the books for a long time.”

Referring to the Department of Labor, Ginder says: “Now they have a mechanism in place to make sure the law is functioning as intended.”

If the DOL comes knocking on the door to see a comparative analysis, self-funded employers are required to provide one or request an extension. After the report is turned in, if there are deficiencies, employers have 45 days to fix the problem.

Comparative analyses are complicated reports and must contain explicit details regarding how coverage decisions were made for each non-quantitative treatment limitation (NQTL) to the following level of specificity:

- The specific plan, coverage or other relevant terms regarding each NQTL and a description of all mental health/substance abuse and medical/surgical benefits to which each term applies

- The factors used to determine that the NQTLs will apply to mental health/substance abuse and medical/surgical benefits

- The standards used to develop the identified factors and any other evidence used to apply the NQTL to all benefits

- The comparative analyses demonstrating that the processes, strategies, evidentiary standards and other factors used to apply NQTL to medical/surgical benefits was equal to mental health/substance abuse

- The specific findings and conclusions that indicate the plan is or is not in compliance with the Mental Health Parity Act.

The department is also on the lookout for lawsuits being filed by policyholders and can use those to start an investigation. If the agency sees a lawsuit, they can request a copy of the insurer’s comparative analysis, which should be prepared.

“You have to treat this as if there is a light being shone,” Ginder says. “There is lots of sunlight that shines on these things when there is a problem. It’s not like it happens in a vacuum.”

The Department of Labor could require a plan to run data that could include, for example, all its claims related to treatment for autism. If the DOL finds that someone was denied benefits, the agency can require a self-insured employer to pay the claims wrongly denied and can impose penalties. The agency usually requires the plan language to be changed at that point.

It also becomes public when the DOL makes a decision. Employers are required to provide notice to all plan participants of a deficiency and any subsequent change in benefits.

“People may come out of the woodwork saying, ‘We wanted this benefit and were denied, and we paid for ABA therapy privately,’” Waltman says, referring to applied behavioral analysis, a therapy based on learning and behavior. “The plaintiff’s bar is getting interested in these cases, too. There’s lots of different ways an investigation can get triggered.”

In lieu of its normal corrective action policy, the Biden administration recently used the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) for the first time to sue UnitedHealthcare, United Behavioral Health, and Oxford Health Insurance. ERISA, a federal law passed in 1974, created standards to protect participants in private health and retirement plans.

The suit showed that UnitedHealthcare and United Behavioral Health (together termed “United”) set provider rates using third-party examples like Medicare. Then, for psychologists, United took a 25% discount and paid 35% less to counselors with a master’s degree. It did not use this same practice on the medical/surgical side for providers such as nurses or physical therapists. The suit also alleged that United disproportionately used utilization management on mental health but not medical/surgical claims. The case was settled in August 2021, requiring the companies to pay $15.6 million in settlement funds to resolve claims and pay penalties.

Employers can also have a problem if plan participants use their right to request proof of parity under ERISA, Smith says. If someone is highly litigious or getting care under workers compensation, their legal counsel is likely aware they can seek this information. “We have a mental health crisis now nationwide, and insurers were supposed to do this a long time ago,” Combs says. “If someone has a child that can’t get a mental health drug and, God forbid, something happens to that child, it’s going to come back to the employer and the TPA.”